The first step is to admit you have a problem. And America, you have a problem. Each year, alcohol abuse costs us $249 billion in lowered productivity, higher healthcare costs, added law enforcement expenses, and motor vehicle accidents. Every year, thanks to booze, 88,000 of us die. And we drink more every year, as the rates of associated liver disease and cancers, as well as fetal alcohol syndrome, increase as well.

Our drinking problem has been with us for as long as we’ve been a nation. Various solutions have been attempted, the most famous being Prohibition, which went into effect a century ago and failed spectacularly.

Alcohol wasn’t always a problem. In colonial times, it was considered a friend that dulled pain, brightened spirits, fought fatigue, and soothed indigestion. It was a medicine with many benefits, and often safer to drink than water. Even the Puritans, for all their disapproval of self-indulgence, didn’t outlaw liquor — there was more beer than drinking water on the Mayflower. In a sermon, Puritan minister Increase Mather referred to alcohol as “a good creature of God,” though drunkards were “from the Devil.”

Drunkenness wasn’t considered a social problem in those days. When people drank to excess, the community dealt directly with them. Drunkards were placed in stocks in the center of town for public humiliation, fined, or whipped. Robert Coles of the Massachusetts colony, who was known for his drunkenness, was made to wear a “D” of red cloth on a white background for an entire year “for abuseing himself shamefully with drinke.”

But as alcohol became more plentiful in the New World, so did its abuse. Within 20 years of the first Kentucky whiskey being distilled, over 2,000 distillers were annually producing over two million gallons of the spirit. Such a large supply drove down its price, so whiskey was not only abundant, but cheap.

One of the first to warn us about the dangers of alcohol was Dr. Benjamin Rush, former surgeon general of the Continental Army and signer of the Declaration of Independence. In 1784, he spoke out against this national pastime, declaring that liquor led men to “immodest actions … roaring, imitating the noises of brute animals, jumping, tearing off clothes, dancing naked, breaking glasses and china,” he wrote. Worse, it robbed men — women had limited access to liquor then — of the power of self-government, a necessity for citizens in a democracy.

His warning was almost totally disregarded. Alcohol was commonly given to women in labor, put in babies’ bottles, and served in business offices. Kegs of liquor were left open for anyone to help themselves to in stores and on steamboats. It was served to judges and juries during trials and considered a legitimate court expense. By 1830, Americans were drinking an astounding 7 gallons of pure ethanol per year per capita, the equivalent of 1.7 bottles of 80-proof whiskey per week for every adult, including the abstainers.

Robert Coles of the Massachusetts colony was made to wear a “D” of red cloth on a white background for an entire year “for abuseing himself shamefully with drinke.”

As the nation grew and the population became more mobile, communities lost their ability to regulate intoxication on their own. Heavy drinking could be observed anywhere, even in church. Renowned Presbyterian minister Lyman Beecher declared that liquor led Americans to become immoral and self-indulgent. “Drunkards reel through the streets,” he said, “day after day, and year after year, with entire impunity. … We are becoming another people.”

In 1826, to halt this moral corrosion, Beecher founded the American Temperance Society. Its cause was quickly embraced by many Americans who shared Beecher’s alarm. Within 10 years, the Society had convinced over 1.5 million Americans to never touch another drop of liquor.

“The temperance movement was a faith-based initiative that demonized drinking,” says historian Garrett Peck, author of The Prohibition Hangover. “It assumed there was no safe level at which anyone could drink any alcohol at all. Start drinking and you were on the road to being a drunkard.”

By the 1850s, the Temperance Society had built up enough support that 13 states passed some form of prohibitory law. Most of these states gave local authorities the right to dictate how liquor would be sold and consumed. New York, New Hampshire, and Delaware had statewide bans on the sale of alcohol. Maine and Tennessee prohibited manufacture and sale.

None, however, made drinking a crime.

The cause of temperance was buoyed by the Second Great Awakening, a Protestant revival movement that aimed to perfect society. Abolishing liquor was one of several reforms being pursued; abolishing slavery was another.

In the wake of the emancipation of slaves after the Civil War, temperance activists felt newly empowered. In 1869, they invited advocates of public education, government reform, open immigration, and expanded voting rights to Chicago. There, they formed the National Prohibition Party, focusing on alcohol’s role in causing chronic illness, joblessness, spouse abuse, child abuse, and poverty.

In Cincinnati, women prayed nonstop at a bar for two weeks, and even rigged up a locomotive headlamp to illuminate the drinkers skulking beyond the swinging doors.

One of the Party’s first acts was to accept women delegates. It was an acknowledgment that women, who could not vote, were often the most abused victims of men’s alcoholism. Wives and daughters could only watch helplessly as their fathers’ and husbands’ drunkenness brought brutality to their homes and poverty to their lives.

Women began targeting the drinking establishments that had taken their families’ money and futures. Their prayer vigils became a common sight outside taverns. In Cincinnati, women prayed nonstop at a bar for two weeks, and even rigged up a locomotive headlamp to illuminate the drinkers skulking beyond the swinging doors.

Through these protests, women discovered a powerful sense of unity, and in 1873 they formed the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which, says Peck, went national with “600,000 members and was very influential. It became part of the progressive movement that sought to use the laws of the land to make Americans better people.” They promoted reformed labor laws and prison conditions as well as women’s suffrage. They protected young girls by lobbying to raise the legal age of consent to 15 (it had previously been 10 years old in some states).

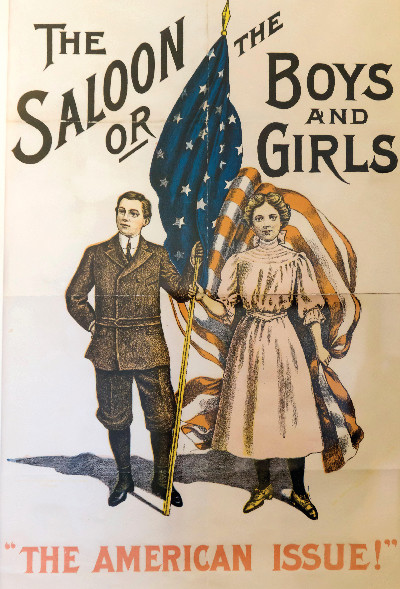

But more radical prohibitionists were not satisfied with these scattershot reforms and, in 1893, formed the Anti-Saloon League. Saloons were a more promising target than alcohol — they were widely believed to be the source of the country’s drinking problem. Many were crime-infested dives, neighborhood centers for gambling, prostitution, and criminal gangs.

The League drew its support from rural voters. Wayne Wheeler, director of the League, regarded cities as un-American and lawless, often quoting a common sentiment: “God made the country, but man made the town.” He appealed to Americans in farm communities who feared the rising power of the cities. Daniel Okrent, author of Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition, says, “Nativists born in the vast middle of America thought they were losing their country. And Baptists and Methodist preachers, who were losing political influence, became the vanguard of the Prohibition movement.”

The Anti-Saloon League presented the alcohol problem as a black-and-white issue and, as Gerald Carson writes in The Social History of Bourbon, their messaging “did not always stick to the truth. Every man who took a drink was an inebriate. His children, if any, could only be mental defectives. Any homicide was a ‘Whiskey Murder.’ If a misguided youth out on the town took a swing at a police officer, it appeared in the papers as ‘Whiskey Reign of Terror.’”

For its first 15 years, the League focused on passing laws to regain local control over the manufacture and sale of liquor. As its successes grew, it gathered the support of powerful men like John D. Rockefeller. In time, Wheeler became so influential that he would be called on to advise presidents on temperance policy and to help pick candidates for crucial government jobs.

In 1914, the Anti-Saloon League proposed a national Prohibition amendment to the U.S. Constitution. “The Wets [anti-prohibitionists] never believed that it would happen,” says Okrent. “People said, ‘how can you amend the Constitution to say I can never have a glass of beer? That’s never going to happen.’”

But the amendment had strong support from Americans convinced that alcohol was bad for family life and American culture at large, says Okrent: “a group that wants to change the law has much more energy and passion than a group that wants to keep laws as they are. They are incredibly motivated.”

And when America was swept up into World War I in 1917, the Anti-Saloon League played on Americans’ xenophobia. It convinced the Justice Department that a number of breweries were owned in part by alien enemies. Wisconsin’s lieutenant governor advocated shutting down breweries, declaring, “We have German enemies in this country … the most treacherous, the most menacing, are Pabst, Schlitz, Blatz, and Miller.”

It wasn’t much of a leap for anti-immigrant forces to embrace the Prohibition amendment. “Since the early 1900s, immigrants had gained political power in the cities,” says Okrent. “The power of the cities was often

derived from saloon owners. Irish, Italian, and some Jewish saloon owners got heavily involved in politics.” Nativists believed that closing the saloons would break the political power of new voters, discourage aliens from coming to the U.S., and might even convince some immigrants to “go home.”

The 18th Amendment, prohibiting the sale of alcohol, was ratified in January 1919, and the Volstead Act, which authorized the enforcement of Prohibition, became law on January 17, 1920.

Even before it went into effect, Samuel G. Blythe was reporting on Prohibition’s early successes for The Saturday Evening Post. In Los Angeles, where Prohibition was already in force, a barber told him that he had more money to spend on the family and the house since he’d stopped drinking. He’d repainted his home, wallpapered some rooms, and bought a piano for his daughters. And he’d wiped out all his debts.

The manager of a big hotel told him that Prohibition had originally cut into his revenues, but they had returned to their old level. Also, there was better discipline in his employees and better behavior among his guests. Other hotel owners found income from their ballrooms and restaurants increasing. Newspaper circulation numbers had gone up. One saloon had been successfully converted into an ice cream parlor.

There were plenty of other optimists. Economists predicted Prohibition would bring prosperity through higher productivity and less absenteeism among workers. Some religious leaders anticipated nothing less than a moral revolution in the country. The histrionic evangelist Billy Sunday said, “The slums will soon be only a memory. We will turn our prisons into factories and jails into storehouses. … Hell will be forever for rent.” Some towns were so confident of the coming redemption of their citizens that they sold their jails.

These good reports led many to think that Blythe had been right when he wrote, “we’ll get used to Prohibition just as we have got used to many other reforms — not like it, but accept it.”

But America didn’t accept it. Prohibition didn’t bring prosperity. The entertainment industry went into decline. Restaurants failed when deprived of alcohol sales. States lost the crucial revenue they gained from their liquor taxes. Prohibition wiped out 75 percent of New York State’s revenue.

There was no rebirth of public morals, either. Crime in 30 major cities jumped 24 percent in the first year, and the murder rate shot up 78 percent. Between 1925 and 1930, violations of the Volstead Act rose 1,000 percent. The homicide rate during the Prohibition years rose from 6 to 10 per 100,000 Americans.

Organized crime grew into a national industry. Hastily hired, untrained revenue agents were frequently bribed by bootleggers. Chicago mobster Al Capone raked in 60-100 million untaxed dollars a year — more than $1 trillion in today’s money. The police chief of Boise, Idaho, said, “Drinking is done almost everywhere by almost everybody,” and a Topeka, Kansas, police chief said, “the girls simply won’t go out with the boys who haven’t got flasks to offer.”

Federal efforts at enforcement were chronically underfunded. Most states couldn’t afford to offer significant help to federal agents. New York refused outright to provide assistance.

“People said, ‘How can you amend the Constitution to say I can never have a glass of beer? That’s never going to happen.’”

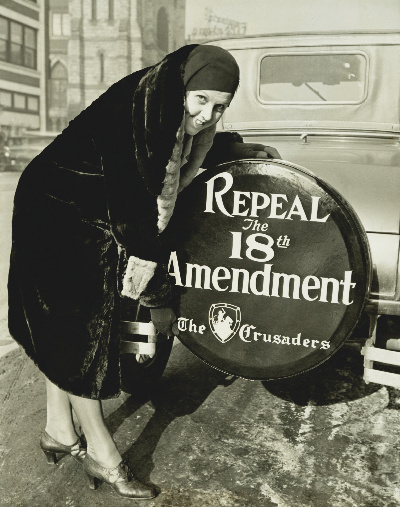

Americans became convinced that “the government’s ability to legislate morality just doesn’t work,” says Okrent. “If people want something that doesn’t have an immediate victim, they will find a way to get it, irrespective of the law.” In December 1933, Prohibition was repealed.

Not everyone was ready to give up on temperance. Although gradually temperance groups faded from view, to this day almost 20 percent of Americans still believe Prohibition is a good idea, according to a 2014 CNN/ORC International poll.

The Prohibition Party still exists, and members like James Hedges are keeping the temperance flame burning. “We put our efforts more into educational work than political work,” he says. The NIAAA — the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, a division of the National Institutes of Health — sponsors and promotes evidence-based research on the medical consequences of alcohol.

The American Council on Addiction and Alcohol Problems claims to be the successor to the American Temperance Union and Anti-Saloon League. In addition to offering education on alcohol and drug abuse, the ACAAP campaigns to reduce liquor advertising, require complete content listings on liquor labels, and reduce the legal level of blood alcohol for drivers from .08 percent to .04 percent — the equivalent of about two drinks for the average-sized man.

The Women’s Christian Temperance Union is still alive and working to convince Americans not to buy, sell, drink, or serve alcoholic beverages. It also reaches out to elected officials, corporations, and media leaders to inform them of the NIAAA’s findings on the health consequences of alcohol.

Prohibition may have proved that the government can’t legislate morality, and it may have wasted millions trying. But the problem Prohibition hoped to solve is not only still with us, it’s worse than ever, as NIAAA Director George Koob said in January when he called for “a wake-up call to the growing threat alcohol poses to public health. Alcohol-related deaths involving injuries, overdoses, and chronic diseases are increasing across a wide swath of the population.”

In this presidential election year, America seems more divided than ever. But the scourge of what Koob calls “a hidden addiction that nobody wants to talk about” afflicts progressives as well as conservatives, President Trump’s base voters as well as Joe Biden’s. The scourge might be generally hidden in the media, but it’s not hidden from its millions of victims and probably not from anyone reading this article. One hundred years after Prohibition, a noble but failed experiment, it’s time for Americans to start talking.

This is article appeared in the July/August 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine to read the entire article.

Featured image: Who’ll stop the drain? Local police in Scranton, Pennsylvania, empty barrels of illegal booze seized from a train during the Prohibition era. (Arthur Miller / Alamy Stock Photo)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

“there was more beer than drinking water on the Mayflower”

Some years back, a book called “From Beer to Eternity” postulated that the Pilgrims made hurried landfall at Plymouth Rock because they were out of beer.