On Tuesday afternoon May 13, 1958, in the top of the sixth inning at Chicago’s historic Wrigley Field, Stanley Frank Musial was announced as a pinch-hitter for the St. Louis Cardinals. Musial was only one hit shy of a Major League Baseball milestone, 3,000 career hits — only seven players had ever entered that exclusive club, and no one since 1942. Ideally, Musial would have loved to break into the 3000-hit club before the adoring St. Louis fans, but if anything best epitomized his career, it was that he was a team player not focused on individual plaudits. With St. Louis down 3-1 with a runner on second base, Musial stepped in as the potential tying run.

Young Cubs right-handed Moe Drabowsky — coincidentally born in Poland where Musial’s father hailed from — peered in for the sign. Musial took his unique stance in the left-handed hitter’s batter box, once described by pitcher Ted Lyons as like “a little boy peeking around the corner to see if the cops are coming.” On a 2-2 pitch from Drabowsky, Cardinals broadcaster Harry Caray delivered his characteristically ebullient call: “Line drive! Into left field! His number three thousand! A run has scored. Musial around first, on his way to second with a double. Holy cow! He came through!” On his first try at 3,000, Musial showed the true mark of a champion rising to pressure.

The moment after Musial hit 3,000, bedlam broke out on the field. Pitchers in the bullpen, where Musial had been tanning himself earlier in the game, ran out to embrace him. Cardinals manager Fred Hutchinson came running out from the dugout to hug his star.

The train ride back to St. Louis was memorable. As George Vecsey notes in his biography, Stan Musial: An American Life, winning pitcher Sam Jones, whom Musial had pinch hit for, presented him with a magnum of champagne. Harry Caray presented Musial with a gift from all the broadcasters, commemorative gold cufflinks with a 3,000 logo. The Illinois Central Railway company provided a big cake with “3,000” in Cardinal-red icing on the top. It would be the last time that the Cardinals took this route; airplane travel had become a necessity as San Francisco and Los Angeles had just entered the National League.

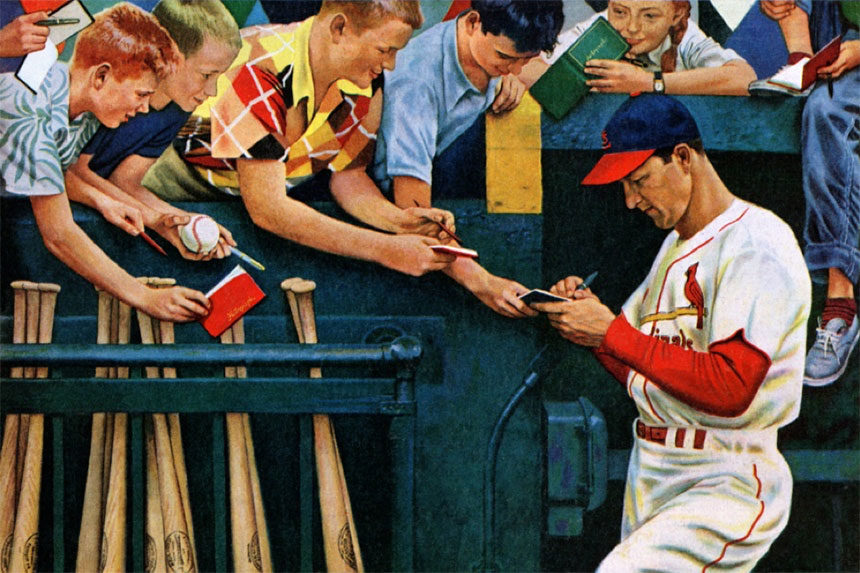

The train was supposed to arrive in St. Louis shortly after 11 p.m., but it was delayed because jubilant fans were pouring out at local stops along the train’s route. At the Clinton, Illinois station, about 50 Cardinal devotees clamored for their hero, shouting: “We Want Musial! We Want Musial!” He waved from the back of the train and stretched out to give autographs. The celebration grew larger when the Cardinals arrived in the Illinois state capital in Springfield. More than 100 fans started singing, “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow.” Musial came out of the dining car to greet and sign for the fans on the platform.

When Musial re-entered the train, he must have thought about another Springfield in Missouri, where in 1941, playing for the Cardinals’ Class C Minor League Affiliate, he mastered the art of hitting after failing earlier in his minor league career as a pitcher. Warm memories flooded back of the good times he had enjoyed in Springfield. As recounted in delicious detail by biographer James Giglio in Musial: From Stash to Stan The Man, he remembered how he instructed the bat boy, “Give me a bat with a hit in it”; how he peppered line drives off the Coca-Cola and 7-Up signs on the right field wall; how he made acrobatic catches in right field that thrilled the fans and showed that he had learned his lessons well from gymnastics classes taken as a youth; how he had gone fishing with teammates and then headed to a local pool hall where they could follow on ticker tape the scores of major league games.

As Vecsey wrote in his book, when the Cardinals train finally pulled into St. Louis’s Union Station near midnight, more than a half-hour late because of the earlier celebrations, nearly a thousand fans greeted Musial. “I never realized that batting a little ball around could cause so much commotion,” Musial told the crowd on the platform. “I know now how Lindbergh must have felt when he returned to St. Louis.” (Thirty-two years earlier, aviator Charles Lindbergh had piloted his plane “The Spirit of St. Louis” across the Atlantic Ocean and returned home to a hero’s welcome.) Seeing many youngsters up way past their bedtime, Musial quipped, “No school tomorrow!” (Musial’s teenaged daughter Gerry told biographer Vecsey that she remembers her mother driving her to school rather late the next day.)

The celebration was not over. High-ranking team officials and a raft of the Musial family’s close friends headed to Stan and Biggie’s, the restaurant that Musial co-owned with partner Biggie Garagnani. Musial didn’t get home until 3 a.m., but he was fresh enough the next day to hit a home run on his first at-bat for his 3,001st hit. He belted two more hits in a Cardinals victory that extended a winning streak that momentarily gave them hope of pennant contention.

Later Missouri Governor James T. Blair Jr. gave him a special license plate with “3,000” on it. Tris Speaker and Paul Waner, two of the still-living members of the 3,000-hit-club, joined the occasion. (The other living members, Ty Cobb and Napoleon Lajoie, were too ill to attend, and Cap Anson, Eddie Collins, and Honus Wagner were no longer alive.)

Looking back at how the Midwest poured out to celebrate Stan Musial’s 3,000th hit, it brings to mind President Harry Truman’s whistle stop train rides ten years earlier. A native of Independence, Missouri and an underdog in the 1948 presidential race, Truman took trains all over the country, stopping in many small towns, speaking from railway platforms to excited admirers, and ultimately winning a surprise victory over Republican candidate Thomas Dewey in November.

As a native of a heavily Democratic town near Pittsburgh, Musial had been happy for Truman’s come-from-behind triumph, but during the 1950s he supported President Dwight Eisenhower. Come 1960, however, Musial enthusiastically supported John F. Kennedy, whom he had met the year before; as Vecsey recounts, Kennedy had impressed him with his youth and energy. “They tell me you’re too old to play ball, and I’m too young to be president, but maybe we’ll both fool them,” quipped Kennedy, who at 43 was only three-and-a-half years older than Musial.

Musial retired at the end of the 1963 season with awe-inspiring statistics: career batting average of .331, 475 home runs, 1,951 runs batted, 1,949 runs scored, and 3,630 hits, second at the time only to Ty Cobb and second only to Babe Ruth in total extra-base hits. “If consistency were a place, it would be lightly populated,” goes the perceptive sports adage. No greater testimony to Stan the Man’s steady performance can be found than in how his 3,630 hits were divided: 1,815 at home and 1,815 on the road. He appeared in a record-tying 24 All-Star games and still holds the record for most home runs in the Midsummer Classic.

It was disappointing that after winning three World Series in his first four full seasons, Musial and the Cardinals never returned to the Fall Classic after 1946. But it was no surprise when in 1969 he was elected on the first ballot to the National Baseball Hall of Fame garnering over 93 percent of the vote. He became a fixture at future Hall of Fame ceremonies, his beloved harmonica in his pocket and ready to be used at the drop of a hat. According to Derrick Goold at the St. Louis Post Dispatch, one year he serenaded the crowd with a serviceable version of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame.”

Unfortunately, in recent years Musial has slipped from memory as one of the all-time greats. Playing outside the major media markets didn’t help his marketability. The departure of the Brooklyn Dodgers to Los Angeles may have also dulled his reputation. Brooklyn fans had given Musial his nickname “Stan The Man” because of how he wrecked the home team with his bat year after year.

But to those who came of age in mid-20th century America, especially in the heartland, Stan Musial remains a paragon of excellence. On the day he retired, baseball commissioner Ford Frick praised him as “baseball’s perfect warrior . . . baseball’s perfect knight.” Musial biographer James Giglio has called him “a true sportsman and a role model . . . . virtually to all.” Two statues of him grace areas near the new Busch Stadium in St. Louis. Former President Bill Clinton remembers growing up in Arkansas doing his homework while listening to Musial’s at-bats on the radio. And when President Barack Obama bestowed the Presidential Medal of Freedom on Musial in 2011, two years before his passing, he extolled him as “an icon untarnished, a beloved pillar of the community.”

Featured image: Saturday Evening Post cover detail, “Stan the Man” by John Falter, from our May 1, 1954, issue (© SEPS)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now