As Americans long for the return of baseball — now indefinitely delayed due to a virus that has shuttered the country — there is no better time to reflect on a soulful interview that sparked one of the game’s most nostalgic human narratives.

In 1960 The Boys of Summer author Roger Kahn was in his early 30s when he drove along backroads bordering streams in the Green Mountains to spend the afternoon with New England poet Robert Frost. When the sportswriter reached the end of a dirt road, he got out of his car and walked up a hill to Frost’s cabin, where he lived alone, from May until the leaves changed in the fall, when the poet returned to Cambridge.

At the time, Kahn was a celebrated sportswriter who covered the Brooklyn Dodgers for the Herald Tribune in the early 1950s. He based The Boys of Summer on players such as Jackie Robinson, who broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball, Pee Wee Reese, Preacher Rowe, Carl Erskine, and Roy Campanella. Twenty years after his Boys retired, Kahn caught up with his middle-aged Boys as they struggled through life.

Kahn had met Frost at the Bread Loaf Writers’ conference at Middlebury College in 1951, where the poet pitched to the writer in a summer baseball game with the spine of the Green Mountains in the background. It was there, on that grassy field, when a love for America’s Pastime connected two artists who appreciated the delicate, often brutal plight of the aging athlete.

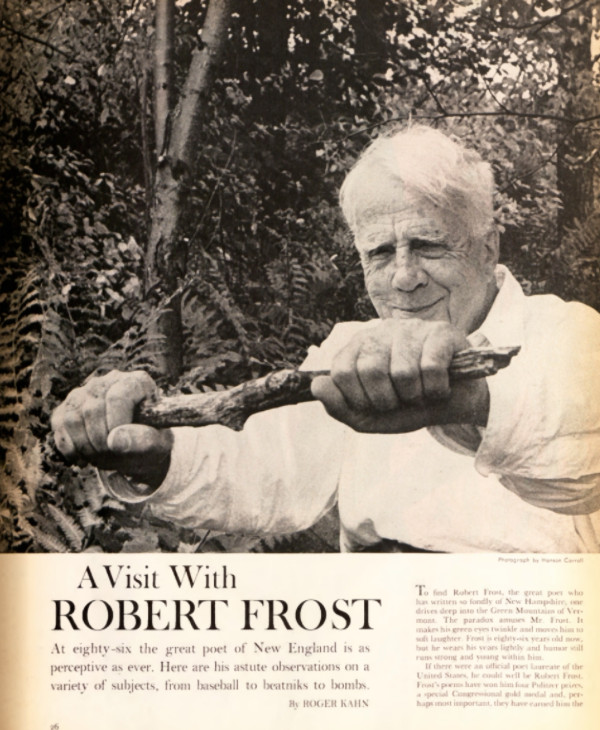

The World Series was a month away when the 86-year-old snow-headed poet greeted Kahn, wearing blue slacks and a ragged gray sweater. With a face as weathered as the mountain, Frost cut a strapping agrarian frame from years of laboring behind a plow, and daily hikes through the woods, where he conjured phrases about the road less traveled.

The Saturday Evening Post’s “A Visit with Robert Frost” interview drew a response that stunned both Kahn and Frost. Hundreds of letters poured into the magazine from readers. Many enclosed the November 19th feature, asking Kahn to autograph it because they knew he captured Frost in his purest form toward the end of his life.

The Interview

1960 was a tumultuous year. The United States announced plans to send its first wave of troops to Vietnam, John F. Kennedy narrowly won the presidential election, the Soviet Union shot down a U2 spy plane, and Fidel Castro nationalized American oil and other interests.

Xerox introduced the first copier and computers with punch cards were transforming society, yet Frost lived like a pioneer in a previous century. He didn’t have a desk. A ragged row of books lined the shelves of his sparse living room. Frost never learned to type and agreed to the interview on the condition that a tape recorder was not used, feeling the device would disrupt the natural flow of the conversation.

Working on a portable typewriter, Kahn noted that Frost “runs a conversation as a good pitcher runs a baseball game, never giving you quite what you expect.” That afternoon Frost paced around the living room, holding his chin in his hands as he pondered the unfinished business of Russia and Castro, two years before the Cuban Missile Crisis captured headlines. As a poet, Frost spoke of beatniks, loneliness, and the natural, unchanging rhythm of the tides. As a farmer, he explained why he thought it was important for people to be self-sufficient and for every man to know how to live poor.

On the ballfield Frost was a pitcher, and a damn good one who didn’t have a problem with players who slid into base, spikes up. He grew up going to games at Fenway Park and rooted for the Red Sox. His favorite player was Ted Williams, whose last game was eulogized by John Updike on October 22, 1960, in his lyrical New Yorker essay, “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu.”

Some of Frost’s most memorable lines compared life to baseball. In a 1956 Sports Illustrated story the poet sat in the grandstand and wrote, “Some baseball is the fate of us all. For my part, I am never more at home in America than at a baseball game.” He also turned this phrase: “Poets are like baseball pitchers. Both have their moments. The intervals are the tough things.”

That afternoon, as the sun lowered over the mountains, Kahn asked his friend, “Is there one basic point to all fine poetry?”

“The phrase,” Frost said, offering this explanation: “A clutch of words that gives you a clutch at the heart.”

A decade later, Kahn clutched readers’ hearts with his true-to-life account of his Dodgers when they hit middle age.

The Last Surviving Boy of Summer

Roger Kahn passed away at a nursing facility in Mamaroneck, New York, on February 6, 2020. As fans from Brooklyn to Los Angeles celebrated his poetic take on baseball, almost all of his “Boys” were gone. Jackie Robinson died at age 53 in 1972, catcher Roy Campanella, who was confined to a wheelchair after a car accident, died in 1993. Pee Wee Reese passed in 1999 and Duke Snider died in 2011, just to name a few.

One particularly resilient player who shared a love of poetry with Kahn and Frost resides in his hometown of Anderson, Indiana.

Ninety-three-year-old Dodgers pitcher Carl Erskine returned to Indiana with his wife and family 60 years ago. Kahn affectionately branded Erskine as “Oisk,” based on the way Brooklyners leaned over iron railings at Ebbets Field, rooting for their boy “Cal Oiskine.”

Erskine grew up pitching into a strike zone painted on the side of a barn. He played his entire career with the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers, from 1948 through 1959. As a starting pitcher, Oisk helped the Dodgers collect five National League pennants, winning the World Series in 1955 against the New York Yankees. At the high point of his career in 1953, Erskine won 20 games and set a World Series strikeout record in a single game on October 2, 1953, in “chilly sunshine” as described by Kahn.

Reporters and writers (like myself) sought out Erskine after Kahn’s passing, asking him questions about the author and his Boys. When I called on a frozen Valentine’s Day, his wife Betty cheerfully answered the phone as the temperature plummeted across the Indiana plains. Erskine was tinkering with something in the garage when he politely came into the house to take my call.

That day he explained why The Boys of Summer will endure as one of America’s most relatable baseball classics. “Roger saw life in more depth than any other beat sportswriter. He drew out the broad personalities of ballplayers in an era of hero worship,” Erskine said.

Kahn always praised Erskine as his most empathetic player. In The Boys of Summer the sportswriter focused on a life decision the soft-spoken Hoosier made to return to Indiana at age 32, staying put to make a better life for his son Jimmy, born with Down syndrome in 1960.

Erskine explained that The Boys of Summer is really two books. “The first part is about Kahn’s childhood, growing up in Brooklyn, where his mother never read him a baseball book, but taught him about Greek mythology, which he applied to ballplayers. The second part is about athletes who age,” he said. The title is derived from the opening stanza of a poem by Dylan Thomas, the struggling Welsh playwright who died at age 39 in 1953. It reads:

I see the boys of summer in their ruin

Lay the gold tithings barren,

Setting no store by harvest, freeze the soils.

The Brooklyn Dodgers

The Boys of Summer was met with mixed reviews when it was released in 1972, when Kahn drank heavily and began to resemble Hemingway with a graying beard. Erskine said Walter O’Malley, who moved the team from Brooklyn to Los Angeles, did not like the book because he felt it played on the bad luck and some of the unfortunate circumstances the players faced later in life.

“Kahn exposed this Dodger team that was snake bit – they all had some tough outcomes in life,” Erskine said, recalling that his roommate Duke Snider was not pleased about the way in which he and his family was portrayed.

“I never felt that way. Kahn’s book reflected what real life is like,” he said very matter-of-factly. “It had nothing to do with how many baseballs you hit or players you struck out – you ended up so human that you were just like everybody else.”

Author Gay Talese, who helped define literary journalism, described Kahn’s narrative as a book about ourselves in the October 26, 1972 issue of The Herald & Republican. “It is about youthful dreams in small American towns and big cities decades ago, and how some of these dreams were fulfilled, and about what happened to those dreamers after reality and old age arrived. It is also a book about ourselves, those of us who shared and identified with the dreams and glories of our heroes.”

After The Boys of Summer was published Erskine mailed Kahn a poem by Robert W. Service, entitled “My Masterpiece” about having good intentions but never following through. The sportswriter framed the poem on the wall by the fireplace at his home at Croton-on-the Hudson, New York. The last stanza reads:

A humdrum way I go to-night,

From all I hoped and dreamed remote:

Too late… a better man must write

The Little Book I Never Wrote.

Though Robert Frost, Roger Kahn, and Carl Erskine came from different worlds, the New Englander, New Yorker, and a Midwesterner will forever be united by a love of poetry and baseball. They also help us understand that some of the roughest and most unpredictable roads that life takes us down make us human.

Austin, Texas, writer Anne R. Keene is the author of The Cloudbuster Nine: The Untold Story of Ted Williams and the Baseball Team That Helped Win WWII, being released in paperback on April 21st.

Featured image: © SEPS

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Just today (11-2-23) reading Anne Keene’s WONDERFUL piece about Robert Frost, Roger Kahn, and Carl Erskine! What a delight!