American lawyer and writer, Arthur Train, was a prolific author of legal thrillers. His most popular work featured recurring fictional lawyer Mr. Ephraim Tutt. In “The Lost Gospel,” an explorer searches the Egyptian desert for lost artifacts that will prove or disprove his faith.

Published on June 7, 1924

For all they that take the sword shall perish with the sword.

“The trouble with Christianity,” said Ismail Bey, “is that it is utterly unpractical.”

“The trouble with Christianity,” said Count Poldolski, “is that we do not really know what Christ taught.”

“The trouble with Christianity,” said Rhoda Calthrop, “is that it has never been tried.”

The party, following the wake of fashion, had come up from Cairo on Calthrop’s dahabeah to see the recent excavations in the Valley of the Kings, and the Cheetah, on whose awning-covered deck they were sitting, was moored along with a hundred other pleasure craft on the east bank of the Nile a mile above Thebes. Ismail Bey waved a sleek white hand across the turbid river toward the red-brown fields that stretched to the Libyan Hills. Under the cobalt arc the whole Egyptian world of palm-rimmed bank, of broken column and ruined temple, as well as the turgid current of the Nile itself, was a welter of dazzling gold, flushed with scarlet and streaked with purple.

“On these sands can be traced the history of all the ancient civilizations — of Assyria and Babylon, of Macedon, Greece and Rome — and of all the old religions.

“Nothing remains of any of them.”

“I thought you were a good Mohammedan, excellency,” commented his hostess.

“I am,” answered Ismail Bey quite calmly. “I obey the sheri’s, I pay the charitable tax, I say my prayers five times a day, I fast during Ramadan, and I have even made the pilgrimage to Mecca. What more is necessary?”

“Faith!” replied Miss Calthrop.

The Egyptian laughed.

“I am a graduate of Balliol,” he said. “All sensible men believe the same thing. What it is no sensible man ever tells.”

“But Christianity remains!” protested the beautiful Princess Zeeka.

“What you call Christianity!” retorted Poldolski. “But does anybody know what Christ really preached? The Gospels are not contemporaneous. They were written many years after the events chronicled therein occurred.”

“Christ gave us a spiritual ideal,” answered Miss Calthrop gravely, “to which we hope the world may some day attain.”

The breeze from the south was stirring the ripples among the sand bars to lavender. Hoopoes and wild pigeons flew downstream — imps fleeing the gates of Paradise, marking the channel to silent boats with widespread lateen sails on their way from Aswan to Cairo and Alexandria, black lacquer on a yellow screen. From an adjacent dahabeah came the insistent rasp of a phonograph playing Papa Loves Mamma. The escarpments to the west smoldered, spraying the sky with gold.

“How mysterious the Nile is!” the princess murmured. “No wonder it is worshiped as a god!”

The Egyptian’s eyes narrowed.

“The Nile,” he replied, “like religion, is born amid the fierce passions of savagery, in the midday darkness of primeval growths, in the ruthlessness of credulity and fanaticism and the strange worship of beasts in the likeness of men — ” He half closed his lids and let the smoke curl slowly from his nostrils as he watched the rose-tinted oval face of the princess. “And like all religions, it eventually disappears.”

“But Christianity does not!” The eyes of the princess were smoldering.

Ismail Bey shrugged.

“If Poldolski is right, your true Christianity may have disappeared already. I do not wish to give offense, my friends; but did not Christ teach self-sacrifice, nonresistance and forgiveness of wrongs? Did he make any distinction between individuals and nations in his teachings? Well — I am, it is true, a Mohammedan — a barbarian, if you will — but to me there is something curiously inconsistent in the application of these doctrines among what you would call the more civilized nations. It is not enough to say that Christ did not mean literally what he said. Does anybody claim that the Prophet Moses or the Prophet Mohammed did not mean exactly what he said? Listen!”

From the circle of sailors seated cross-legged in the bow of the dahabeah came the monotonous thump of a daraboukeh. “Al-lah!” they chanted fiercely. “Al-lah! Al-lah! Al-lah!” The cry rose harsh and nasal in the silence of the sunset.

“Those down there do not doubt that when they die they will go instantly to Paradise,” said the Egyptian.

“That is my point, excellency,” agreed the Pole. “The words of the Koran came from the lips of Mohammed. Christ did not write the Gospels. His meaning has always been the subject of controversy. It is conceivable that the discovery of a new Septuagint might change our entire viewpoint.”

“Like that found by Tischendorf in Saint Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai,” suggested Professor Troy of the Azar. “Such manuscripts occasionally turn up. There must be hundreds of them hidden away in ancient libraries or among unexcavated ruins. Our three chief sources of knowledge concerning Christ’s teachings are the Alexandrian manuscript in the British Museum, Codex A, as we call it; the Vatican manuscript at Rome, Codex B; and the Sinaitic, Codex Aleph, at St. Petersburg; and they all range from about 300 to 450 A.D. But the prior existence of certain others is well established — the Lost Gospel referred to by Saint Hermanticus, for example.”

Major Bagley, of the Camel Corps, put down his glass.

“Oh, I say! Have you heard of that too? I always thought it was just another Arab yarn, like the vanished oasis of Kurafra.”

“It’s more than a yarn,” replied Professor Troy. “There are many references to it in the writings of the Fathers. The Fifth Gospel is alleged to have been written in Latin by a member of the household of Pontius Pilate. It is a tradition, you remember, that Procula, Pilate’s wife, secretly visited the Saviour in prison before his crucifixion and became a convert. The story is somehow mixed up with that.”

“What is supposed to have become of this Lost Gospel?” asked Miss Calthrop with interest.

“It is said to have been brought to Egypt, where it disappeared. What have you heard about it, Bagley?”

“I’ve heard such a story, or its first cousin, told around many a caravan fire in strange places,” answered the officer. “Curiously enough, it is usually associated with the legend of Kurafra — the City Devoured by the Sand, as the Bedouins call it. The desert is full of such tales.”

“It always gives me a funny feeling to hear the Arabs refer so casually to historical characters — almost as if they were still alive,” remarked the hostess as she handed Ismail Bey his tea. “But in Egypt the past and the present are one.”

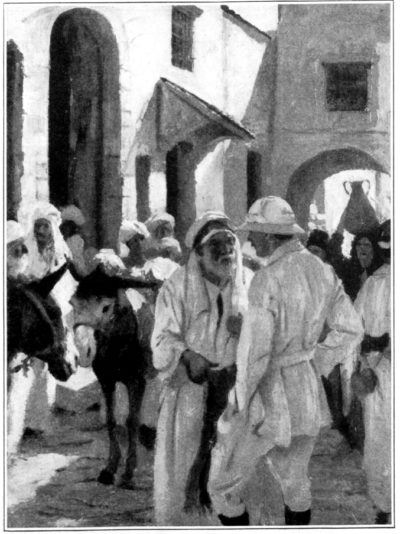

From behind the high bank against which the Cheetah was moored came the syncopated warbling of a flute, closer at hand the creaking of the shadoofs used in the days of Amenhotep. A procession of fellahin carrying tools and baskets, of boys on donkeys, of female figures bearing jars upon their shoulders, moved along the edge of the bluff — children of the Pharaohs sprung to life from the temple walls.

The hostess’ brother, Hugh Calthrop, who had been sitting by himself in the Cheetah’s stern, arose and came forward with a paper in his hand. He was an emotional young fellow, given to doing things on the spur of the moment.

“Look here,” he said, pulling his short mustache nervously, “this is certainly very queer.” He poured himself out a drink.

“Did any of you ever know Paul Trent?”

“I seem to have heard the name.” Professor Troy rubbed his chin as if to stir the magic lamp of recollection.

“Of course,” answered Miss Calthrop. “He used to come to our house in Chicago almost every Sunday afternoon. But wasn’t he killed in the war?”

Calthrop held up the paper.

“I have just had a letter from him!”

“From Paul?” exclaimed his sister incredulously. “But he has been dead ten years!”

“Exactly. This letter which you saw handed to me not ten minutes ago by Yussuf was written to his mother in January, 1914. It’s been wandering around ever since.”

“How is that possible?” asked the Princess Zeeka.

Ismail Bey glanced at her quizzically.

“When you know Egypt better, dearest lady, that will not surprise you.”

“I do not care to know Egypt any better,” she answered coldly. “Please tell us about the letter.”

Calthrop pulled a chair into the group and sat down.

“It’s certainly weird — a voice from the dead and that sort of thing. Trent was a young Egyptologist of Chicago University, out here on his sabbatical. He wanted to do a little original work, and I let him have some money. The last I heard he was in Jerusalem. Then came the war. I assumed, naturally, he’d managed to enlist, and thought no more about it. Anyhow it would have been no time to hunt for missing archeologists. But when the show ended Trent didn’t turn up. Meantime his old mother — who always refused to believe that he would not come back — died herself. I was her executor. The State Department made some sort of an investigation and traced him as far as Bukara in company with a German named Harnach-Hulsen. They simply vanished into the desert.”

“But the letter!” cried the princess. “From where did your friend mail it?”

“It was written in the desert and given to a passing caravan for Siwa. Heaven knows what happened to it. Perhaps the Arab put it in his pocket — if Arabs have pockets — and just forgot it. Or it may have been tucked into a pigeonhole in Bukara or Siwa, or left lying around until it was picked up by somebody who decided that the easiest thing to do was to stick it in the mail — as perhaps it was.”

“But how does it come to you?” asked Professor Troy.

“Because, having been delivered through the mail to Mrs. Trent’s address in Chicago, it has been forwarded to me here as her executor.”

“After all,” commented Ismail Bey, “ten years is not so long for a letter to go ten thousand miles. That is a thousand miles a year. Out here we should call that fast.”

“I will read you the letter,” said Calthrop.

“WESTERN DESERT, BUKARA.”

January 6, 1914.

“‘Dearest mother: You will already have got the letter I mailed you from Cairo on Christmas Day, and learned how at the monastery of the Benedictine Monks of Beuren in Jerusalem I had the luck to stumble upon Max Harnach-Hulsen, the famous German Egyptologist, who became tremendously interested in my theory that Roman and possibly Persian remains would very likely be found in the Libyan Desert north of the Oasis of Beharieh in the direction of the Fayum. My funds were getting rather low and to my great delight he agreed to join forces with me. Otherwise I couldn’t have gone. It appears that the Emperor William II personally is putting up for him and so of course he had first to wire Berlin. Meantime we went on by rail to Cairo for the holidays, and there I found your dear little present. I shall always wear it, mother dear. Thank you a thousand times.

“‘Well, a few days later H-H got a reply from the Kaiser, offering to supply all the necessary funds on the condition that the funds should go to the University of Berlin or, as he put it, “to my people.” That seems fair enough. And I may say there has been no lack of money. Well, we made our arrangements and got off by rail before New Year’s to Medinet-el-Fayum and from there to Beharieh, making the balance of the journey to Bukara by motor and camel. Here it really looked as if we might be badly hung up on account of the difficulty of finding any camels not infected with hump disease. However, H-H, who is an authoritative person, an officer in the Landwehr, went to the gendarmerie and saw the omdeh and made a big noise about the Kaiser, and the first thing I knew we had all the camels we wanted — beautiful slender hajins such as one never sees except in the desert. So this is really goodbye.

“‘I like H-H immensely in spite of his gruff manner, which really doesn’t mean anything. He is a big, reddish man about six feet two, with cropped hair, a thick neck and very large hands and feet, a man of iron — physically and intellectually a reincarnation of what I imagine Bismarck to have been. He is very chummy with the Kaiser and belongs to a sort of dining club of which General von Bernhardi, Admiral von Tirpitz, and the Prince-Bishop of Breslau also are members. He has shown me several very intimate letters from William II, whom he admires extravagantly. In fact he classes him with Hammurabi, Moses, Abraham, Mohammed, Charlemagne, Shakspere and Lincoln.

“‘Well, he may be everything H-H says, but as I don’t know the gentleman, I’m no judge. Anyhow, he must be a clever chap. H-H is obsessed with the idea that there is danger of the Germans, who used to be the best fighting men and most warlike nation in Europe, becoming what he calls a too peace-loving nation. He says that what they need is a shock to reawaken their warlike instincts. I can hardly keep my face straight when he is getting off this bunk. In some ways I feel that H-H isn’t much more sympathetic to me than one of our Arab camel drivers. But he is a regular he-man for all that, and we are great pals. So, good-by again, mother.

Your loving son,

“PAUL.’”

Calthrop turned the letter over dramatically.

“Now listen to what is written in pencil on the back:

“‘Jan. 23.

“‘Dearest mother: We have made the greatest find in history. I cannot say more now, but we shall both be famous. I am forbidden to reveal its nature, but you will soon learn. We are about two hundred kilometers from Bukara. I have promised Harnach-Hulsen not to say where until we make a formal announcement. I have just time to scratch this off and give it to a passing Bedouin who is on his way to Siwa. God bless you, mother. Hur-rah! Hurrah!

“‘PAUL.’”

A gray dusk distilled itself along the canals; the surface of the Nile was a steel mirror clouded here and there by the breath of the night wind. A felucca came down midstream, a ripple spreading wide from her bows, her oars swinging to a muffled chantey that might have been the barbaric ritual of some equatorial deity.

“Bismillah!” muttered the Egyptian. “I wonder what they found.”

“God only knows what they found,” answered Calthrop. “But I am going to find out.”

“Hugh,” cried his sister, “you don’t mean you are going to — ”

“Yes — tomorrow. I’m starting for Beharieh, not in the hope of finding Trent, because of course he’s been dead ten years — but of finding what he found.”

There was no sound but the clutch and whisper of the current along the dahabeah’s sides.

“You’d be crazy to try anything of the kind!”

Bagley tossed his cigarette overboard definitely.

“There’s not a drop of water between Bukara and Siwa, and none in the direction of the Fayum. Rohlfs nearly died there in ’72. Our flyers have scoured the desert in every direction around there for five hundred kilometers. Besides,” he added, “I doubt if the frontier districts administrator would give you a permit.”

“All the same, I’m going!” declared Calthrop. “But I won’t risk anybody’s life but my own. I shall go to Bukara, look up some of the Arabs that went with Trent and start out from there. You couldn’t expect me to do anything else!” he exclaimed.

The princess looked at him meaningly. “No,” she said; “no one could expect you to do anything else.”

Calthrop thrust the letter in his pocket and stood up.

“I’m going down to collect my duffel,” he remarked. “The Cairo train leaves at nine.”

He walked alone to the stern again. The Nile was jet. Night had fallen. To his excited imagination it seemed alive with mysterious noises — faint cries and distant shoutings, the neighing of horses, the tramp of legionaries, the crash of arms, the rumble of chariot wheels; while from the bow came the never-ceasing throb of the daraboukeh and at intervals the lonely cry of “Allahu akbar! Allahu akbar! La ilaha illa-llah!”

II

“In the name of God, the compassionate, the merciful: I On the blessed day of Friday, 28th Rabia eth Thani, 1332, there came to our town Bukara the honored Max Harnach-Hulsen, the German, professor of the honored Zawia of Berlin, and also the honored Paul Trent, the American, professor of the honored Zawia of Chicago in the Etats-Unix, and they are carrying the orders of the great and honored General Sir Martin Crafts; and according to the exalted orders we met them with great honor and hospitality and congratulated them on their safe arrival to us. We hoped that God may be exalted, would grant success to their efforts, and return them safe and victorious in the best condition for the sake of the Prophet.

“(Signed) “The Second Adviser of Bukara, Amed El Sussu, May God forgive him.

“The Judge, OSWAN EL BARASSI, May God forgive him.

“The Adviser, SAYED MOHAMMED IBU OMAR EL FADHILL, May God forgive him.

“The Wakil of the Sayed at Bukara, MOHAMMED SALEH EL BASICARI, May God forgive him.”

Thus had read the only official record of the visit of the two archaeologists to the town of Bukara; the only record, in fact, since although Calthrop had stayed there a week he had found no other clew to them. Yet unless all the Arabs who had accompanied Trent and Harnach-Hulsen had died of thirst, one or more of them should be still living in the oasis. He was in the absurd position of having a caravan on his hands and with no idea of where he wanted to go. Inquiries of the omdeh elicited only the customary shrugs and the positive assurance that there were no archaeological remains in that part of the country, for in spite of the difficulty of travel every inch of the Western Desert under the control of the frontier districts administration — which was responsible for the safety of all country not watered by the Nile between the Sudan and the Mediterranean — had been covered time and again by the Camel Corps Patrol. Those who had followed the regular caravan routes to Siwa, to Taizerbo, to Kebabo, on the way to the Tebu or Lake Chad, or to Dachel on the south, had never heard even so much as a whisper of any such place as Kurafra.

And then the omdeh ventured to give Calthrop a piece of advice. Why not, he suggested, instead of starting off blindfold into the desert, without any definite objective, enlarge his caravan and make the trip to Siwa, the ancient site of the Temple of Jupiter Ammon, where he could visit and photograph the rock tombs of the Karit-el-Musabberin, the temple of Aghormi and the ruins at Ummebeida?

Calthrop thanked him and let it go at that. Eventually he caused it to be known throughout the bazaar that he would pay one hundred pounds gold to anyone who would guide his caravan to where he could find any trace of the missing men. Then and then only did Mohammed Ali Ibrahim ben Rahim make his appearance, a desiccated Berber with a skin like a lizard’s, and eyes as sharp and glinting.

“Not of my own knowledge,” he protested, “but by that of my sister’s son, Mohammed Yussuf el Bulaki, the peace of God be on him. For he is no longer living, being taken in his sixty-first year, while I, full of years, am still alive at eighty-two. Neither did I hear it from his own lips, but by hearsay from my sister Fatima, after her son, my nephew, was dead; for I was then dwelling at Siwa, where my grandsons were in attendance at the Zawia, and I heard it from her after she was a widow and had come to dwell with me. Nevertheless, by the accuracy of her repetition am I able to guide the gentleman’s caravan to the spot described by my nephew, for he noted the course by Jerdi, as we call the North Star, in its relation to certain other minor stars and by other methods which it is not necessary to go into.”

And now it was sunset of the fifth day out from Bukara.

“Adaryayan!” shouted Ibrahim. “We have arrived, oh, sick ones!”

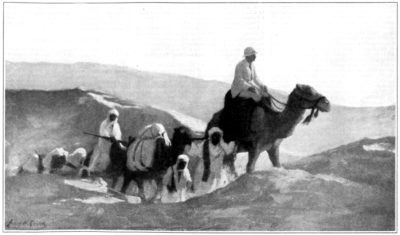

The caravan halted in the hatia in the lee of the dunes and two of the baggage camels dropped to their knees. Calthrop, mounted on a fast hajin, had ridden on ahead and was already on the top of the next gherd. As far as his vision carried, one snow-white dune lifted beyond another. All day long they had climbed ridge after ridge under a sun that scorched through helmet and kufiya alike, until now the dispirited camels trailed their heads and gave off that acrid odor which is the inevitable concomitant of thirst. They had had nothing to eat since the third day, when the prickly, juiceless bush of the Mehemsa, sometimes found under the ridges, had entirely disappeared. Now the poor beasts struggled along, limping and wavering, and when they stopped tried to eat the stuffing of the baggage saddles. “Haya alla Salat!” came the call to prayer from below.

“Haya alla Salat!”

Already the Arabs were at their devotions — making kibla, as it is called — washing their hands in the sand, prostrating themselves, and praying with a quick glance over each shoulder and a muttered ejaculation to drive away the evil spirits supposed to be lurking behind them. To Calthrop, sitting alone upon his hajin and looking down upon them from the top of the gherd, it no longer seemed fantastic that these children of the desert should people it with jinn and houris, see the finger prints of Allah upon the drifting sands and hear the voices of his angels in the lisp of the night wind along the wadis.

The setting sun burning upon Calthrop’s back told him that he, like the rest of them, was facing the sacred Kaaba a thousand miles away, toward which amidst this desolate waste of sand they turned as unerringly as the compass needle swings to the magnetic pole. He had always thought of the desert as a dead thing like the surface of the moon; odorless, silent, for the most part motionless; a place of intolerable solitude. To his surprise he had found it quite otherwise, even amid the fantastic desolation of the apparently lifeless dunes. It had not amazed him to find the flat stony plain about Bukara spotted with gray gorse, a grazing ground for sheep and camels, to see long lines of hamlas come stalking over the horizon’s rim laden with ivory and feathers from Wadai and Lake Chad, to find the news of the Near East discussed with passionate earnestness by fadhling caravans; in a word, to find the Western Desert teeming with activity. But what astounded him was that here, far from the routes of the Jalo, Anjela, Siwa, Jaghabub and Darfur caravans, amid the weird, curly hummocks that stretch like an ice flow between Bukara and the Fayum, frequented only by the scattered descendants of the fierce bandits who lurked there in the days of the Romans, where all vegetable growth is extinct and not even a desiccated bush breaks the blinding smoothness of the surface, where no jackal or cony can survive, and where water does not exist — that here he should feel no loneliness, but on the contrary a curious sense of familiarity with it all, as if he had been born, lived and perhaps died there. He was filled with an exalted sense of the power and mystery of God, the unity of all things physical and spiritual, of being guided and directed, of his own essential participation in the affairs of an unseen world. The wind bore across the ridges a faint odor of myrrh, a curious scent of the desert, of the untarnished earth itself; it lifted the white sand from the crests of the gherds and sent it trickling, sifting and whispering in tiny avalanches down into the hatias, seeming to drive the snowy dunes before it like the billows of a mighty sea that swept on and on, irresistible, relentless, inevitable, like the tide submerging whatever came in its way. Indeed, Professor Troy had said that the gherds did move and for that reason were known as traveling dunes; that once the whole Libyan Desert was a well-watered and fertile country supporting a considerable degree of civilization, but that gradually the desert sea that washed the southern edges of its oases had encroached upon and smothered the inhabitants, filling their cisterns, absorbing their lakes, blotting out their villages and towns, rising higher and higher until it submerged even their temples and their hills, driving the population toward the seaboard on the one hand and the Nile upon the other.

From the hatia rose the pungent scent of dung-fed fires and the grumbling roar of the camels. The black goats’-hair tents had been pitched and the water girbas and bales of supplies arranged in a zareba, or hollow square. Supper would be ready in a few minutes. Calthrop was ready for it in spite of his swollen tongue, his burning throat, his inflamed eyes and his cracked lips and gums. He had expected and discounted all that. What he had not fully previsioned was the vast waste of sand through which now for nearly a week the camels had patiently struggled up and down, slipping and sliding, sinking at times almost to their knees. There were no tracks of any sort. Whatever wandering Bedouin might pass that way left no trace behind him — spurlos versenkt. The sun, the wind, and Jerdi, the North Star, are the only guides in this part of the Western Desert. Yet the guide, Mohammed Ali Ihrahim ben Rahim, had never faltered. But another day and they must find water. The camels could last but three or four more at most.

He swept with his glasses the sea of foaming breakers that came rushing toward him, one behind the other, higher and higher. A wisp of sand curled lightly along the top of the gherd like a whiplash. The hajin raised its head, which it had lowered almost to its knees, and wriggled its cushioned lips. It, like its rider, felt a call to something. Then the light dimmed to purple and at the same instant his eye caught a gara, or tabular hill, strangely rectangular in this tipsy curving world. It might, of course, be a trick of shadow, but he knew that a straight shadow can be cast only by a straight line. He looked again. Behind the gara, clearly defined against the side of one of the gherds, was a pyramidal gray patch. He glanced back over his shoulder. The sun was sinking in a whorl of flamingo feathers. The cohorts of the gherds gleamed with purple and gold. Calthrop tightened his rein and plunged down the other side of the dune, urging his hajin to top speed.

There is no twilight in the desert. The sun dies in a single iridescent moment. Yet, when, ten minutes later, Calthrop pulled in his sweating hajin there was still light enough for him to determine that what towered above him against the pale saffron of the afterglow was beyond peradventure the peak of a pyramid. In three tiers it rose to a point fifty feet above the floor of the hatia, terminating in a single massive block. On three sides the engulfing sand rose nearly to the top, then fell away sharply on the fourth, revealing cracks and apertures almost large enough to permit the passage of a human being.

Breathless, he peered through the dusk along the hatia. Surely it had a curious and significant regularity of form — this sandy ravine in the lee of the gherd — like a giant avenue. He hobbled the hajin and walked along the hatia for a hundred yards until, climbing imperceptibly, he found himself standing upon the top of the gara. His hobnails grated harshly; he kicked and struck stone; he was standing upon the pylon of a submerged temple. Kurafra!

He stood there stirred to his heart’s core at the visions conjured by his imagination. Here beneath his feet Amenhotep or Rameses the Great, or possibly even Nimrod, the Assyrian conqueror, had marked the western boundary of his kingdom. Here under the lash had strained thousands of slaves, glistening black giants from Ethiopia, from Numidia and from the distant oases of the west. Here some proud monarch, now a mummy, had raised his shrine to the great Ammon and, reclining with his queen like an Egyptian Canute upon the rim of the desert sea, had looked out across the sandy waves and bidden them to advance no farther. How they had mocked him!

The line of light on the western horizon had vanished. Like lamps turned on by an unseen hand, the firmament unexpectedly blazed with stars. Above, the night was girdled with a sash of silver dust.

Calthrop realized that he could not possibly find his way back to the camp in the dark, but the Arabs would know that he must be nearby and he could rejoin them at daylight. With blanket, haversack, canteen and shamadan, or wind candle, he could be perfectly comfortable. Flashlight in hand, he began looking for a likely spot to sleep. Throwing the circle of light along the surface of the pyramid, he examined the crevices until he found one large enough to creep into, and then worked his body through the aperture and crawled along, turning the ray of light ahead toward the interior. Reddish brown, the rough sandstone leaped toward him, then the gleam lost itself in darkness to reflect a darker surface some thirty feet distant.

Getting to his feet again, Calthrop fished his baggage through the crack behind him, and clasping it in his arms crept along the sandy floor into the chamber, or hollow, under the dome. Clearly he was not the first to be there, for in one corner lay the charred remains of a fire and not far off the skeleton of a sheep. There was also about half an alof, or bundle of fodder, and this he took outside and tossed to the hajin. Then he lit the shamadan, spread out his blanket and prepared to make himself at home.

By the time he had eaten the contents of his haversack, drunk the hot coffee from his vacuum bottle and lit a cigarette he was in a mood of exultation. It was reasonably certain that he was sitting in one of the pyramids that fringed the once-fertile strip watered in ancient times by the great Wadi al Fardi, which had flowed through Taizerbo to Jaghabub and thence past the oasis of Siwa to the Nile. Henceforth Kurafra would no longer be a myth but an actuality. But for how long? As vain to attempt to dam the ocean as these steadily advancing dunes of sand. Another year or so and pyramid and temple might disappear forever.

Lifting the shamadan above his head, Calthrop examined the walls. They were devoid of ornamentation. This upper chamber obviously had played no part in the religious functions of the priesthood of Amon-Ra. There was no means of telling whether the last visitor had been there ten, ten hundred, or ten thousand years ago. Higher up where the walls drew closer together it was harder to see, and Calthrop, who was an agile climber, managed to get a few good handholds and swing himself up nearly to the capstone. For a moment, badly winded, he hung there in the darkness like a bat, looking down between his feet at the glow from the shamadan. Then holding himself by one hand while he braced himself with his feet, he peered with the flashlight into every aperture.

Everywhere it caught on rough ocher-red surfaces except one, where some smaller stones had been heaped together. Pushing them aside he disclosed a blackened box, or receptacle, about eighteen inches square. His position was awkward; he had but a single free hand and that held the light, and as he shifted the object to his shoulder his foot slipped. For a moment or two he swung there and then fell heavily to the floor below, striking his head a violent blow against the edge of his find.

When he came to himself he found that he was severely bruised from head to foot and suffering from a sprained wrist. The flashlight was smashed to atoms. He lay there several minutes more, trying to collect himself, while the wind shrieked and roared through the cracks of the pyramid.

The gibleh had brought the sand storm and it was evidently centering among the ruins of Kurafra. And then Calthrop remembered the casket, and in spite of his pain crawled to his knees and shifted the light from the shamadan this way and that along the floor until he found it lying unharmed nearby. The hide of which it was made was black with age and hard as iron, and the peculiar shapelessness of the affair gave it somewhat the appearance of an enormous dried shark’s egg. With the shamadan elevated upon his haversack, he sat down and lifted the casket upon his knees. As he did so he found that he was trembling.

“Nonsense!” he said aloud. “It’s probably empty anyhow!”

His heart beat like a tom-tom as he grasped the cover, and when he attempted to lift it the leather hinges broke, discharging a small cloud of fine dust. Raising the shamadan above his head, Calthrop looked inside.

III

“I lifted the shamadan above my head and looked inside,” said Calthrop. “Try to picture to yourself what a tremendous moment that was for me! I was pretty well done after six days on camel back. I’d traveled nearly two hundred and fifty miles. I’d fallen twenty feet and given my head a beastly knock. I’d just discovered the ruins of a city that no white man knew existed. I was more or less lost in the heart of the Libyan Desert. I didn’t know whether I was ever going to get back or not, and I had a queer feeling that I wasn’t alone in the place. I can’t explain it.

“All those elements combined to give the performance a curious feeling of unreality. Was I there, or was I dreaming it? Or was I someone else? Was I sitting cross-legged inside a pyramid five thousand years old, holding this thing on my knees, or where was I? And outside the gibleh was shrieking like all the demons of hell let loose, and the sand came rattling and sifting through the cracks and swirling across the floor. The shamadan flickered and burned blue. I seemed to hear shouts and screams all around, above and below. And that box wasn’t mine! Yes, I confess it, I hesitated a few seconds before lifting the cover. And then I did! At first I couldn’t make out anything, and then I saw there was a mess of papers and — Well, I’ll show you what I found, exactly as I found it.”

Calthrop got up from the dinner table at which they were seated and went to his cabin. He had returned from his trip only that afternoon, but the members of the party had already learned the details from General Hunter of how the caravan had nearly perished of thirst seven days from Bukara, had been found by a flyer sent out by the Frontier Districts Administration, and how Calthrop himself had been finally rescued by a troop of the Camel Corps Patrol under Major Bagley himself.

He was hollow-eyed, burned black, with cracked lips, almost a wreck, but obviously laboring under an exhilaration that approached hysteria. Something had happened to the man; something that had profoundly affected him; something concerning which they had not cared to ask him.

He returned, carrying the casket in his arms, and they watched him breathlessly as he held it above the candles. The only sound was the lap of the current against the river bank, the scream of the frogs, the chanting of the sailors, to the faint pulsations of the daraboukeh. Through the plate-glass windows of the saloon a white moon looked in upon a table decorated with flowers and silverware. The Princess Zeeka, smoking a tiny cigarette in a long jade holder, sat with her chin in her hands, her elbows among the wineglasses, her eyes fastened expectantly upon Calthrop’s face.

“Move those glasses, will you?” he said to his sister. “Push the candles nearer together please, excellency. Yes, I want you all to have the story just as it unfolded itself to me, step by step. What that box contained might have changed the whole history of civilization!”

He waited while Miss Calthrop arranged the glasses, then placed the box in the center of the table and opened it.

“This is what I found!”

And Calthrop held up to their astonished gaze a Roman short sword and scabbard, with its accompanying belt, thickly studded with semiprecious stones. Even after two thousand years the facets of the jewels reflected the candlelight undimmed. Professor Troy examined it carefully.

“Extraordinary! It is of the time of Tiberius. Congratulations, Calthrop. You’ll be famous. Even the coins of Hadrian found in the Fayum created a sensation, and they were nothing to this.”

But the princess looked slightly disappointed.

“I see that you were joking,” she said. “All you meant was that a sword might have changed the destinies of Europe.”

“Wait a moment,” he answered excitedly. “No, I did not refer to the sword, but to something else — that the box once contained.”

“What was that?” asked Ismail Bey. “And what has become of it?”

“These will tell you,” he replied, lifting a bundle of letters. “Do you read German easily?” he asked the princess.

“I do not like to read German,” answered Zeeka.

“Give them to me. I will make a try at it,” said Professor Troy. “I spent three years at Heidelberg in my extreme youth.”

“How soiled they are!” exclaimed the princess. “I am glad I do not have to read them.”

“Do you remember our conversation about Christianity the evening before I left,” went on Calthrop, “and how the professor told us about the legend of the Lost Gospel, and suggested that — ”

“By George, Calthrop!” exploded Troy. “This is a letter from William Hohenzollern, former Emperor of Germany!”

“That does not interest me in the least,” remarked the princess.

Troy wiped his glasses and spread the crumpled sheet upon the snowy damask before him. “Listen,” he commanded,

“‘AT THE MANEUVERS,

“‘August 20, 1913.

“My dear Harnach-Hulsen: I trust that by this time you are safely at Jerusalem. You remember our interesting talk about a year ago, when Cardinal Kopp, Prince-Bishop of Breslau, and our friends Von Tirpitz and Von Bernhardi were present, and we discussed the biological aspect of war. At that time your remarks struck me as of great force. When you have the time I should be glad to have you set them down in writing. I shall see that they are disseminated through the proper educational, military and ecclesiastic channels, in order that the virility of my people may not be permitted to decay through the insidious and demoralizing influence of an effeminate desire for peace which dominates our age and threatens to spoil the soul of the German people according to its true moral significance. War is not merely a necessary element in the life of nations, but an indispensable factor of culture, in which a truly civilized nation finds the highest expression of strength and vitality.

“‘In answer to the query in your last letter, I distinguish between two different kinds of revelation — a progressive historical revelation and a purely religious one, paving the way to the future coming of the Messiah. As to the first, there is not the smallest doubt in my mind that God constantly reveals himself through the human race created by Him, through some great savant or priest or king, whether among the heathens, Jews or Christians.

“‘The second kind of revelation, the more religious kind, is that which is introduced from Abraham onward, slowly, but with foresight, all-wise and all-knowing, the actual revelation of the Almighty.

“‘Is not His Word our authority? Delitzsch, as a good theologian, should not forget that our great teacher Luther taught us to sing and believe, Das Wort sie sollen Lassen stehn.

“‘It must be our guide, until the Messiah, announced and foreshadowed by the prophets and psalmists, shall at last declare himself. In what form or when the Messiah.may appear no one knows. It may be in the far future or he may be on earth among us even now, unrevealed save to those who perceive and understand, beggar or emperor. But the day arrives!

“‘Unfortunately the condition of her majesty has become worse. My heart is filled with the most grievous sorrow. God with us!

“‘With heartiest thanks and many greetings, I remain always,

“‘Your sincere friend,

“‘WILLIAM I. R.’”

“A characteristic epistle, but not highly illuminating,” declared Ismail Bey. “What else have you got there, Calthrop?”

“Did not this same emperor recently remarry?” the Princess Zeeka inquired of Troy.

The professor ignored her, for he regarded her as a bore. Besides, he was engaged at that moment in wondering whom William had in mind in penning the words “beggar or emperor.”

“Yes, dear lady, he did remarry,” answered Ismail Bey. “But having deprived him of the occupation of war, you should not begrudge him the consolation of love.”

“The next in order is Harnach-Hulsen’s answering letter to the Kaiser,” said Calthrop. “Will you help us out again, professor?”

Troy nodded.

“I knew Harnach-Hulsen years ago at Heidelberg. I recall him chiefly as a duelist for the Saxe-Gothas. He had quite a record.”

“Well, here is his letter. It is a long one. Take your time.”

Professor Troy drew his chair toward the table so that the candlelight fell upon the bundle of sheets in his hand. They were covered with a fine running script.

“He dates his epistle from the Pyramid Emperor William II,” he remarked dryly, glancing at his host.

“‘Jan. 29, 1914.

“‘Imperial and Royal Majesty and All-Highest Lord: With most humble gratitude I acknowledge Your Majesty’s wire received at Cairo. I can already say without egotism that Your Majesty’s interest in this expedition has borne surprising fruit. I have in fact made discoveries of the highest archeological importance, in their way rivaling those of Schliemann.

“‘To take matters in order: After leaving Bukara we proceeded northeastwards toward the Fayum for five days without finding water, although assured by our Berbers that there were desert wells within a distance of two hundred and fifty kilometers. They may have had some sinister plan. I do not trust these people. The only way to get along with them is by dominating them absolutely. The traveling was exceedingly difficult owing to the immense dunes of white sand thrown up by the wind, which drift quite a long distance each year. To cross these dunes is slow and exhausting work, and it is better where possible to follow the hatias between them and to cross at the low places. It is hard to shape any very definite course.

“‘However, on the seventh day, about sunset, when our camels were giving signs of exhaustion, I thought I saw from the top of one of the dunes, at a distance of about a mile, something projecting from the sand that looked like an outcropping of limestone. To my great excitement this proved to be the top of a small pyramid almost entirely submerged; and shortly, at about the right distance, we came upon the two pylons of a temple. It is probable that had we not discovered these they would have been obliterated entirely by the moving sands within a few years.

“‘Here we established our camp and, having measured and photographed the surface remains, began excavating on the side of the pyramid toward the temple, where the stones appeared to have been previously tampered with.

“‘We are proceeding slowly also to excavate the outer surface of the pylons, and have already laid bare not only the usual hymns to Amon-Ra and Sebek, the crocodile god, but also inscriptions made during the reign of Darius and added to by Nektanebes, as well as a Greek inscription in sixty-six lines dating from the second year of the reign of the Emperor Galba, A.D. 69. We have named the pyramid, subject to your gracious permission, the Pyramid of the Emperor William II.

“‘We broke very easily through the outer wall of the pyramid and found a rough passage leading to an unfinished empty chamber. Charred embers and a roll of matting upon the floor showed that robbers had once used it for a hiding place. Concealed in a recess, we found a small chest containing a jeweled belt and short sword, a few gold coins and a papyrus many meters in length. This last appears to be a sort of journal, in the form of a letter addressed to the Emperor Tiberius at Capri by one Gaius Marcus Claudius Silenus, a Roman gentleman traveling in the East under the imperial protection. The Latin text is hard to decipher, probably owing to the fact that it was written in many different localities and under varying conditions. I am translating it as fast as I can with due regard for our other work.

“‘The manuscript is dated at Thebes, in the seven hundred and sixty-sixth year of the founding of the city of Rome, and after the customary complimentary salutations to Tiberius begins with a brief statement that the writer, having killed many crocodiles and lions — these last with the aid of hunting cheetahs of the celebrated breed trained by the Ptolemys — has learned of the ruins of an ancient city called Kurafra lying on the edge of the Western Desert, which he contemplates visiting.

“‘He then proceeds to give a long and unnecessarily detailed account of his travels in Cappadocia, Armenia and Syria, where he was the guest of Herod Antipas, tetrarch of Galilee, on his way to Caesarea to stay with his cousin, Claudia Procula, wife of Pontius Pilatus, the procurator of Judea. He describes Herod as a drunkard, unfit for kingship, and laboring under the delusion of being the Messias of the Jews, and declares that he caused the murder of Iokanaan because the latter denied the truth of his claim. I regard this as of some historic interest, as it is in flat contradiction of Josephus.

“‘I find the work of translating the papyrus most fatiguing, as I have broken my reading glasses. The manuscript contains a description of the miraculous healing of Joanna, the wife of Chuza, Herod’s chief steward, by the thaumaturge known as Jesus, or Joshua, of Nazareth, whom Iokanaan had proclaimed to be the Messias of the Jews, and who was working many miracles throughout Galilee and Samaria. Silenus writes that there is no question about the authenticity of the various cures, since Chuza and Joanna are truthful people, as is also Jairus, a prominent citizen of Capernaum, whose little daughter was brought back to life by the prophet. He also tells how a Jew named Lazarus was similarly raised from the dead, and recounts many restorations of lepers, paralytics, palsied, deaf and dumb, and those officially certified as insane. He describes the great excitement attendant upon these miracles, and mentions a letter that he has received from Claudia Procula, his cousin, asking him to look into the matter with a view to the possibility of inducing the prophet to come to Jerusalem to try to cure Pilate of diabetes.

“‘Silenus then tells of how he went on in the company of Herod Antipas, Herodias and Salome, her daughter, to Jerusalem, where Pilate, who had come up from Caesarea for the Feast of the Passover, was occupying the palace of Herod the Great. He describes how annoyed Antipas is at finding the palace in which he was brought up as a boy commandeered by the Romans and how it has resulted in a certain coldness between himself and the tetrarch, whom he had just been visiting on the friendliest terms. Here he finds to his surprise that his cousin Procula is already, without as yet having seen Christ, more than half a convert to his teachings, fully believing that he is the long-foretold Messias of the Jews. He also related how Pilate is very unpopular with all classes, but particularly the Pharisees, and how they are always plotting his removal by trying to lead him into acts giving the impression that he is disloyal to the emperor.

“‘Then comes a description of Christ’s entry into Jerusalem, his cleansing of the temple, and of his accusation by the officers of the Sanhedrin of treason to Caesar, as a result of which he is placed under arrest and brought before Pilate.

“‘Next follows an account of how Silenus is sent secretly to Christ with an offer of freedom if he would cure Pilate of disease, which is refused, and of the trial of Christ, with its background of political plot and counterplot. Pilate, fearful that unless he accedes to the demand of the Sanhedrin and turns Christ over to them he will be accused of treason to Rome, recalls the presence of Herod in the city and accordingly seeks to escape responsibility for either the release or the delivery of the prisoner to the Jews by sending Silenus to Herod with the suggestion that, as Christ is a Galilean, he comes within the latter’s jurisdiction. But the tetrarch is too wily to be caught and sends the prisoner back to Pilate at the praetorium, inwardly pleased at the dilemma in which the Roman procurator finds himself.

“‘Silenus describes how Pilate, realizing that he cannot evade his duty, becomes greatly disturbed, and representing that he will take the case under advisement sends Silenus to Christ to interrogate him as to his actual doctrines and to determine whether they are treasonable. Procula, unknown to her husband, insists on going with him. They find Christ in a dungeon of the Sanhedrin and have a lengthy conversation with him. They also seek him out later and continue the discussion of various phases of his doctrines, more particularly with respect to the ultimate determination of contested issues.

“‘I cannot say that these alleged interpretations of Christ’s philosophy, even if genuine, add anything to the German theory of culture so often elucidated by Your Royal and Gracious Majesty to Von Bernhardi, Von Tirpitz and myself. In fact it may so easily cause a natural confusion and misunderstanding as to our biological point of view that it perhaps would better be suppressed in the higher interests of the state. I am in grave doubt as to what course to pursue, as any suspicion of our discovery on the part of the public would doubtless result in the demand for a complete disclosure, the refusal of which might arouse unfavorable inference.

“‘Would that Your Gracious Majesty were here to direct my thoughts into harmony with the purposes of Almighty God! I am writing this letter in the unlikely hope that I may be able to transmit it to Bukara by some passing caravan.

“‘To my great satisfaction, I learned from your telegram that there had been an improvement in the health of Her Majesty. May God help further.

“‘With the deepest respect, unlimited fidelity and gratitude, I am, All-Highest, Your Imperial and Royal Majesty’s most humble servant,

“‘MAX HARNACH-HULSEN.’

“Mashallah!” shouted Ismail Bey. “Where is this papyrus?”

He started to look into the casket, but Calthrop restrained him by a touch upon the shoulder.

“A moment, excellency, if you please! Let us take one thing at a time. There is still one other paper — an unfinished letter from Trent to his mother. That letter I will read to you myself:

“‘PYRAMID WILLIAM

“‘Jan. 29, 1914.

“‘Dearest mother: At last I can tell you the marvelous news! We’ve found Kurafra! Do you realize what that means? You can’t blame me for being excited. Who wouldn’t be? But Kurafra is nothing to what we found there! Our caravan had a terrible time crossing the dunes, and we were nearly all in when we found the pyramid that marks the site. Of course we both went nearly crazy. I’m sure Harnach-Hulsen would have got drunk if there had been anything to get drunk on but laghbi. As it was, he made a long speech and toasted the Kaiser in lukewarm coffee. Then he had a sort of dedication ceremony and baptized the pyramid. “I name thee Wilhelm der Zweite.” It was funny as anything, although he took it dead seriously.

“‘I didn’t grudge it to him, for I found the Lost Gospel! H-H didn’t! He may claim to, but he didn’t! I got climbing around inside the peak of old Wilhelm Secundus, and there it was, in a box, where it had lain for nineteen hundred years! You see, Marcus Claudius Silenus, who wrote it to send to the Emperor Tiberius … evidently hadn’t time to finish it at Jerusalem and so he took it along with him when he started off to hunt for Kurafra in 31 A.D. H-H says that what undoubtedly happened was that Silenus was murdered by robbers who hid their booty in the pyramid and forgot to come back for it, or were killed or something.

“‘Anyhow, we’ve got it! And it’s the greatest find since the Sinaitic parchment, the Codex Aleph as they call it, and infinitely more important. For it is an actual Fifth Gospel, in which the writer has written down with the greatest care the exact words of Christ about a lot of things that have always been the subject of argument. For example, regarding the individual ownership of property. But, far more important, his ideas about war! This wonderful old papyrus is going to change everything. The language is so simple, yet so beautiful and convincing. Only to think that the fingers that wrote the letters that are lying now before me had just touched those of Jesus! I can’t sleep. I can hardly eat. With this direct revelation and injunction from Christ’s own lips, there can never be any such thing as war again!

“‘Harnach-Hulsen does not seem very well. I am afraid the heat has done him up. He has been acting very queer and grouchy for a couple of days. He — ”

“Why did he not finish the letter?” asked Zeeka.

“That you must judge for yourself.” Calthrop placed the letter with the others and poured himself a glass of brandy and soda.

“Now to go back a little, let me resume my narrative. I’ve told you how I fell with the casket in my arms and hit my head and probably passed out for a while; and how I finally came to, grubbed around for the box and opened it. Finding the sword, of course, gave me a stupendous kick; but naturally it was nothing to the thrill I got out of the letters. I’d give a lot to be able to paint the thing for you exactly as it was.”

He hesitated, put down his glass and fumbled for his words.

“You see, a very queer sort of thing happened. I’m the last person in the world for that kind of an experience. The wind was raising Cain all around and through the pyramid and the flame of my shamadan kept flickering — what’s the word they use? — ‘guttering,’ I guess — and made weird shadows all over the place and gave me a feeling that I was not alone in there. I could feel — presences — emanations or something. And as I read the letters — it’s hard for me to explain — I can only describe it by saying that I lost my time sense; or rather, as it were, I saw time as a whole — going both ways at once. I — well, I seemed to be detached from the whole business. It was as if everything had telescoped — reversed itself or something — and turned inside out. It was quite weird, I can tell you.”

He shut his eyes and passed his hand across his forehead.

“Of course the bang on my head had something to do with it, no doubt — exhaustion and all that — but I found myself looking very intently at the flame of the shamadan. I suppose there is such a thing as autohypnosis. Anyhow, at first it seemed to be just a blur of radiance. The air was full of flying sand and the flame danced and wavered and tore at the wick — and right there It — whatever It was — happened.”

He pulled one of the candles in front of him. Through the window a broad, glittering moon path lay like a silver drugget across the Nile. Calthrop pointed into the flame.

“As I looked,” he said slowly, “the blur focused — if you get what I mean — and everything became very clear — and distinct — and still — and small. I seemed to be inside the flame, looking out, and at the same time to be outside looking in, and seeing myself in there looking out, as if the whole thing were going on at the wrong end of a spy glass and I had gone through. I know it sounds quite mad.”

He laughed nervously.

“Anyhow, it was all more like feeling than seeing; a visual awareness, if there is such a thing, that I was sitting there inside that blooming pyramid in the middle of a sandstorm fishing inside the box by the light of the shamadan. And I felt sure — you’ll probably think me an utter idiot — that there was something in there near me that I can’t possibly describe. The flame burned up bright again until the inside of the pyramid was bright as day and I could see right through it as if it had been made of glass. And out of the middle of the light a great thing like a gigantic seesaw ran up through the pyramid into the sky — into eternity. It said ‘Don’t touch it!’ Then I knew that It was myself and that the seesaw was Time. I found that I was sliding along it, faster and faster, until I was shooting out into space with the velocity of light. As I flew I saw everything that ever happened. You’ve seen those moving pictures that illustrate Einstein’s theory, showing a human being shot into space at such a rate of speed that he goes flying back through the centuries, overtaking and passing the former years? Well, it was like that, you know. I saw everything that ever happened — only backwards.

“I saw the desert floor sinking lower and lower and the pylons of the temple lifting higher and higher, until temple and pyramid both stood free and clear of the sand and joined by a long avenue of sphinxes. I saw caravans of camels and Bedouins on fast hajins — hawk-faced men with cruel mouths — coming and going. I saw the pyramid being built and the slaves dragging the stones into place up an inclined spiral plane that wound around it. The country was soft and green and covered with palm trees, and the air was sweet and laden with moisture. And then I came rushing down aslant time again and seeing it all forward instead of backwards, the desert sand drifting in, the pylons and the pyramid sinking back, back, until I was looking into a fire surrounded by a circle of peering Arab faces, and then I saw that the fire was my own shamadan and the circle of faces was the same face repeated over and over again — the face of old Ibrahim, who was sitting cross-legged there behind me.”

Calthrop laughed again — apologetically.

“How he had found his way there across the dunes in that sandstorm I can’t imagine, but there he was, and his presence gave me considerable relief. He said that he had stood outside for a long time and shouted to me, but the wind must have carried away his voice. I had begun to feel very chilly. Ibrahim went snooping back in the darkness and came back presently with a handful of brush and a few cakes of camel dung, with which we built a fire, and then I pulled out my brandy flask and mixed a couple of stiff drinks with the water from my zemzemieh. He showed no reluctance about taking it.

“Did you ever see an Arab partly boiled? It’s a very curious sight. I fancy we were both pretty well lit up. At all events, he told me the story of his life, and whenever he showed signs of weakening I’d give him another drink. He was eighty-two years old, he said, and had seen many, many things. I let him run on, and by and by he got down to what I was after.

“It was, he said, in the thirteen-hundred-and-thirty-sixth year of the Hejireh that there came to their town of Bukara a red gentleman, a khawlija el hamri, named Harnach-Hulsen, and a white gentleman, a khawaja el abiad, named Trent. When, however, they learned that these gentlemen sought to find Kurafra the Forbidden City, which Allah had caused to disappear, they were afraid and refused to go with them; but eventually the strangers overcame their fears with gold, and they went. Then he, Mohammed Ali Ibrahim ben Rahim, from the knowledge handed down to him by his great-grandfather, who had it from his great-grandfather, led them here in five days’ journey, to their great joy. Now, there was at that time a well in this place which has since filled with sand.

“Accordingly they made their camp at the other end of the hatia beside the well, but the two gentlemen pitched their tent outside the pyramid and Ibrahim remained with them to serve them. Each day they superintended the digging, and transcribed what was written upon the walls of the temple and made photographs. At night they were busy inside their tent. When they found the chest inside the pyramid they were both very much excited and abandoned everything else in order to decipher the parchment. They sat about all day, and because of the heat in the tent they went inside the pyramid and worked there, coming out at evening and mealtimes.

“Then one night they had a violent row. Ibrahim did not know what it was about, but he felt sure it had something to do with the papyrus. It was a still, moonlit night and the Arabs could hear the red gentleman shouting inside the tent at the other end of the hatia. They, of course, did not know what he was saying; but they could make out references to the Prophet Christ and the phrase ‘mahr ve khareb,’ signifying ‘annihilation.’ The voices rose higher and higher, until the Arabs became very much terrified, and at length the two gentlemen came out of the tent. The khawaja el abiad had the box in his arms and the khawaja el hamri was trying to take it away from him. The struggle became so violent that the entire contents, including the sword, fell out upon the sand. The white gentleman grabbed the papyrus, thrust it behind his back and began pleading with the red gentleman. But the latter seemed to have gone mad, for he picked up the sword and drove it through the white gentleman’s breast. Then he wrenched the papyrus out of the hand of the dead man and threw it into the middle of the fire.”

Calthrop’s lips quivered as he reached into the box and removed a blackened stick to which adhered a charred irregular strip of parchment about two inches wide.

“Ad Tiberium Cmsarem Imperatorem Capreae,” spelled out Ismail Bey. “Magistro Meo Salutem Mashallah! It is a part of the letter to Tiberius!”

“The Lost Gospel!” whispered Calthrop. “All that is left of what might have changed the destiny of the world!” And he burst into tears.

There was a prolonged silence. The princess laid her hand gently on Calthrop’s arm. Her own eyes were wet.

“Do not cry,” she said. “Please do not cry!”

“I’m sorry,” he answered. “I’m a bit strung up.” He ground his handkerchief into his eyes. “Well, after Harnach-Hulsen had burned up the papyrus he went back into the tent, and Ibrahim and the other Arabs ran away. When they came back in the morning Trent was dead and Harnach-Hulsen was still in the tent.”

He stopped and took a sip of water.

“And what became of the German?” asked Imail Bey.

“That is highly significant,” said Calthrop. “When the Arabs realized what had happened they were so fearful lest they should be accused of the murder that they killed Harnach-Hulsen and buried the two of them in the same grave.”

Again he paused.

“So the world will never know — ” began his sister as she stared at the fragment of burnt papyrus. Somehow the past seemed very close to all of them — the past which is part of the present, and of the future. From the neighboring dahabeah floated laughter, the tinkle of silver upon glass, the wheeze of the phonograph playing The Barnyard Blues, while myriad frogs shrilled in the shadoofs — lineal descendants of the same batrachians that had sung to sleep the infant Moses and acclaimed his finding by the daughter of the Pharaoh. A great star hung like a sconce of liquid fire over the Temple of Karnak — just such a star as had guided the Magi to the manger of Bethlehem, where lay the infant Christ.

“There isn’t much more to tell,” said Calthrop at length. “Ibrahim said the rest of the Arabs had never returned to Bukara and that he himself had lived in Siwa for five years before going back to his family. His story had pretty well knocked me out. The wind was shrieking outside the pyramid, the fire was almost dead, and it was getting terribly cold in there. I wouldn’t have cared if Eblis himself had been waiting for me out there in the hatia. I threw the things into the casket, bundled up the rest of my stuff and told Ibrahim that I was going back to the caravan no matter what. He protested at first; but finally he gave in, and we went out and found the camels huddled against one another, half buried in sand. The wind nearly tore me off my beast’s back, and whirled my blanket and raincoat in flapping circles above my head. The air was a thick sheet of stinging, biting dust and grit that cut like glass. The screaming gusts seemed to tear my eyes from their sockets. All sense of direction was blotted out, like the sky. One could only feel.

“I don’t know how we ever made the caravan or how we managed to stick it out when we did. But eventually the wind died down, and by dawn the sky was clear and the air still. By nine o’clock the heat had become suffocating. We were seven days from Bukara, and without water our chances of getting back there were small. While the Arabs were packing the camels I climbed up to the top of the gherd from which I had spied the pyramid the night before. What I’m going to tell you isn’t the least queer part of it all either. There wasn’t a sign of either temple or pyramid left! During the night the sand had completely covered both. The desert had finished its job!”

He lit a cigarette at one of the candles.

“Bagley’s told you the rest, of course — how they spotted us with a flyer and the Camel Corps Patrol picked us up about ninety kilos out of Bukara. You can bet I was glad to see them! I had to abandon my caravan but they gave me a fresh hajin and — Well, here I am!”

He began gathering up the papers. Ismail Bey watched him, frowning. “An efficient person — from his own viewpoint — this Harnach-Hulsen,” he mused. “But the world would never have accepted it.”

“Very efficient; very learned,” agreed Professor Troy. “And if you will believe it, as a young man, very sentimental.”

“Didn’t he write a book on Civilization and Decay?” inquired Rhoda Cafthrop.

“Yes; and in it he gave warning of the danger to civilization of the rising tide of barbarism. The Kaiser gave him the Black Eagle for it,” said Troy.

“How beautiful the sword is!” exclaimed the Princess Zeeka. “How the hilt sparkles! I know many of the stones. We have them in Russia, set in our icons. There is beryl and topaz and turquoise and lapis lazuli. Even a sword can be very beautiful.”

Ismail Bey, holding it under the candles, drew the blade part way from the jeweled scabbard. The princess examined it eagerly.

“How bright it is, in spite of its great age!” she said. “Is it not strange for such an old sword to be so blight?”

The Egyptian turned it slowly. The silken shades of the candles tinged the blade a dull red.

“What is that thin black line under the hilt?” asked the princess.

Ismail Bey glanced at her through his eyebrows.

“That, dear lady,” he answered reverently, “is the blood of a very gallant gentleman.”

For several minutes there was no sound save the chirping of the frogs and the melancholy challenge, “Allahu akbar! La-ilahah! Al-lah! Al-lah!”

Then a footstep clattered in the passage, and Hawkins, the wireless operator, immaculate in white duck, entered, cap in hand.

“Beg pardon,” he said, “but Jerusalem is broadcasting, and — the French have just entered the Ruhr!”

Featured image: Illustrated by James H. Crank / SEPS.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now