Today, we all know the names of Santa Claus’s nine flying reindeer — or at least we think we do. But what is behind those names, and which ones have changed over the last 200 years?

January 7, 1826

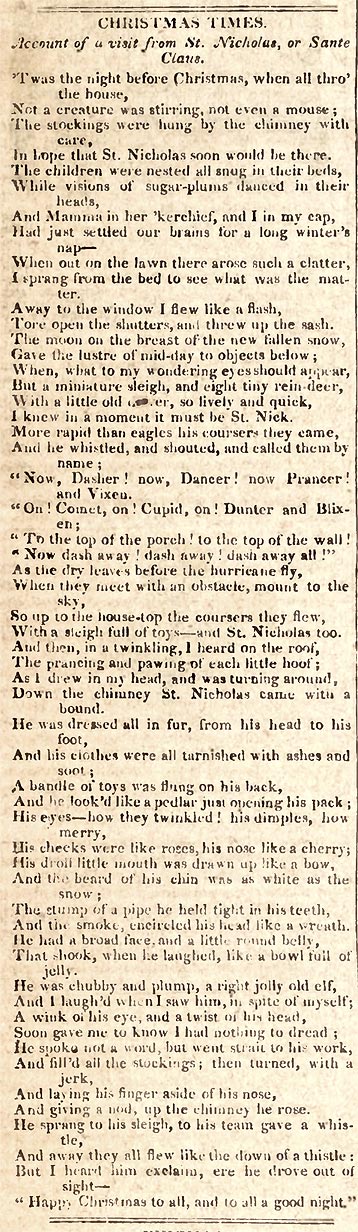

The names of eight of those reindeer first appeared in the poem we know today as “The Night Before Christmas.” It was first published anonymously on December 23, 1823, in a newspaper in Troy, New York and became an immediate hit that was published and republished for years in papers across America under the title “A Visit from St. Nicholas.” The Saturday Evening Post even printed it in its January 7, 1826, issue.

But the man responsible for penning the poem remained a mystery until 1836, when Clement Clark Moore, a Bible professor from New York City, took credit for it. He even included it in a volume of his poetry published in 1844. However, the family of another New Yorker, Henry Livingston Jr. — who died shortly after the poem’s first publication and before Moore took credit — have long claimed that he was the poet. More recent research has reinforced that argument.

Regardless of who wrote the poem, it is the first to include Santa’s reindeer and call them by name. They weren’t names passed down from Old World folklore, but were created by the poet. Whether they were chosen for their meanings, their colloquial connotations, or simply for their rhythm and rhyme, we’ll never know. But the names do have some history, and they perhaps aren’t all exactly as you remember them.

Dasher

A dasher is simply one who dashes. Dash appeared in Middle English as dasshen in the 14th century, probably from the Middle French dachier “to drive forward.” Two types of “dashing” appeared in English at about the same time: There’s the “moving quickly” dashing, as in “dashing off to the store,” and there’s the “striking suddenly and violently” dashing, as in “being dashed against the rocks.” The poet probably had speed in mind when he chose this name — it is, after all, a poem for children — but some writers do have a knack for slipping in opaque little adult-themed jokes in their children’s stories.

If there is an adult insinuation here, there’s an even more frightening possibility. By 1800 — meaning it likely would have been known to the poet — dash was also being used as a euphemism for damn. Considering that Santa Claus’s raison d’etre is to be extremely judgmental of children, having a reindeer that hints at the ultimate naughty list wouldn’t be out of place. (It’s unlikely, sure, but not implausible.)

Dancer

Dance — from which the name Dancer is formed — has an unexpectedly muddied history. We know it entered Middle English in the 1300s as dauncen, from Old French dancier “to dance,” but that’s where certainty stops. Though French is well known as a Romance language — that is, it’s derived from the language of the Roman Empire — dancier isn’t derived from Latin: The Latin word for “dance” is saltare. Etymologists aren’t certain exactly where dancier came from; it’s possibly from an old Frankish dialect that predates the expansion of the Roman Empire into northern Europe.

Prancer

The history of prance is similar to that of dance. It, too, appeared in Middle English in the 1300s, as prauncen, and its ultimate source is debatable. Some theories about its provenance include the Middle English pranken “to show off,” from the Middle Dutch pronken “to strut, parade” (and the source of our word prank), or from a Danish dialect word prandse “to go in a stately manner.”

Regardless of where it came from, the word was originally used to describe horses — and it eventually found its way, in this poem, to a different hoofed animal.

Vixen

Going back to Old English fyxen, vixen is a feminine form of fox. Today, vixen is more commonly used to describe a sexually attractive woman — especially on the big screen — but that extended meaning hadn’t been established until the mid-20th century, so the poet couldn’t have been hinting at that. But there was another extended meaning of the word that had been around for centuries by the time the poem was written. Even dating back to the time of Shakespeare, vixen was a derogatory term meaning “an ill-tempered woman.” The poet certainly would have understood this meaning, so this particular choice of name is interesting.

Comet

The Great Comet of 1811 was a memorable marvel that the poet most certainly would have experienced. It was visible to naked eye for 260 days in 1811 — a record that stayed untouched until the Hale-Bopp comet of 1997 visited our solar system. A mysterious body that hurtled through the night sky must have seemed the perfect name for a reindeer that did the same thing.

Comet itself goes back to the Greek kometes “long-haired,” describing the comet’s tail in the night sky. It journeyed from Greek through Latin and Old French before arriving in English sometime before the 12th century.

Cupid

Cupid was the Roman god of erotic love, the son of Venus and Mercury. (Greek mythology gave him the name Eros.) This seems like an odd choice for the name of a reindeer in a Christmas poem that has nothing at all to do with sex or romance. However, Cupid had long be depicted as a winged god, so perhaps it was his ability to fly that the poet had in mind when he named this reindeer.

The Donner Party

This is where it gets a little weird: When the poem was first published, there was no Donner in it. The next reindeer on the list was Dunder, which was, according to Snopes, part of a common Dutch exclamation, “Dunder and Blixem!” — meaning “thunder and lightning.”

Henry Livingston Jr., it should be noted, had a Dutch background, while Clement Clark Moore came from British stock.

Another publisher soon changed Dunder to Donder, perhaps to more closely mimic the common pronunciation. (The Post seems to have rendered it as Dunter when we printed it in 1826. Was this an editorial decision or a printmaker’s error? We may never know.) When Moore added the poem to his collection in 1844, he retained this change to Donder.

Donner (the German word for “thunder”) wouldn’t make an appearance until the turn of the century, and it wouldn’t be cemented in our collective conscience until 1949, when Gene Autry popularized the Johnny Marks song “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.”

From Blixem to Blitzen

And yes, the last of the reindeer named in the poem was originally called Blixem, the Dutch word for “lightning.” This was changed in pretty short order to Blixen, probably to better rhyme with Vixen. (The Post used Blixen in 1826.) In 1844, when the poem appeared in his collected works, Moore — perhaps knowing more German than Dutch — changed the name to Blitzen, the German word for “lightning.” But if Moore did know German, it is odd that he kept the spelling Donder instead of altering it further to Donner, as we know it today.

Rudolph

Glowing-nosed Rudolph was a latecomer to the herd. Created by Robert May in 1939, the story of Rudolph was created as part of a Montgomery Ward Christmas promotion — a giveaway to children who visited Santa in their stores that year. Rudolph didn’t become a mainstay of Christmas in America until, as I mentioned earlier, Gene Autry recorded and popularized “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” in 1949.

The name Rudolph comes from the Old High German Hrodulf and literally means “fame-wolf” — an odd choice for a character depicted as a handicapped underdog. May wasn’t thinking about etymology, though. The name was chosen primarily for its alliteration; documents show that, as he was working out the story, May scribbled down a number of other possible names — including Rollo, Reginald, and Romeo — before deciding on Rudolph.

Featured image: “Reindeer in the Night Sky” by Manning de V. Lee, Dec 1, 1954. Copyright © SEPS.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now