This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

One morning early last spring, my younger son and I were in an argument as I drove the boys to their respective schools. The subject was (in hindsight) entirely silly and unnecessary, but we both felt passionately about our positions and weren’t backing down. The argument continued right up until he got out of the car, which meant that (to the best of my recollection) for the only time during that entire school year, we didn’t say “I love you” to each other as he got out. I spent the remainder of the day paralyzed, unable to think about anything other than the possibility of a school shooting and of that angry drop-off being our last interaction.

Guns and gun culture in America have long been fraught and contested topics, subjects that quickly and potently divide us, issues that any public American Studies scholar addresses at his or her peril. I don’t expect to convert anyone to a radically different perspective than their starting point by writing about them here. But as stories of yet another school shooting unfold, I wanted to use my Considering History column to highlight a few histories that are, at the very least, relevant to engaging in these 21st century conversations.

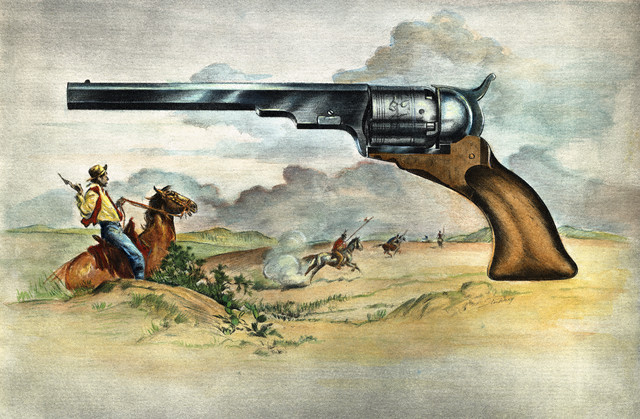

When it comes to scholarly works that trace the foundational, influential presence of gun culture and violence in America, the gold standard remains Richard Slotkin’s trilogy of books about the frontier: Regeneration through Violence: The Mythology of the American Frontier, 1600-1860 (1973); The Fatal Environment: The Myth of the Frontier in the Age of Industrialization (1985); and Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America (1992). Slotkin’s use of “myth” in each subtitle doesn’t mean that he isn’t also tracing historical realities of guns and violence, but rather that his argument across all three projects is that those material realities became the basis of extended mythologies, cultural narratives that associated gun-toting historical figures (from Myles Standish and John Smith to Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett to Wyatt Earp and Annie Oakley) with foundational American values of freedom and independence (among others) — and that in the process turned stories of brutal violence into images of iconic heroism.

That’s all part of America’s story and identity, at every stage. But the Constitution represented something quite different from, and indeed in many ways contrasted to, such myths. The Constitution was an attempt to construct a legal and civic groundwork for the new and evolving nation, one in which its ideals were wedded not to icons but to ideas, not to stories but to structures. And as it did with so many aspects of early American society, the Constitution overtly addressed guns, as part of the Bill of Rights that George Mason and others fought to include in the document before the Constitution could be ratified by the states. The Second Amendment in that Bill of Rights reads in full: “A well-regulated Militia being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms shall not be infringed.”

Less than 30 words, in a complex sentence where the first dependent clause directly modifies the second independent one. Moreover, many of those words, including “well-regulated,” “Militia,” and “Arms,” have ambiguous meanings (individually, in relationship to each other, and in different historical contexts) that have become the source of extended debate. But one thing that the sentence’s grammar makes clear is that this is a collective right, one intrinsically tied — in a moment when the United States did not yet have a standing army, possessed no governmental military force that could defend the nation against foreign enemies — to the ability and indeed the necessity of Americans gathering in groups to help with communal and national “security.”

One important follow-up question, of course, was what that meant for individual Americans outside of such a collective role, and even (perhaps especially) in opposition to the government. The Constitution was silent on such questions, but just two years into his first term as president, George Washington had an occasion to address them. As I traced in this prior Considering History column, the March 1791 Whiskey Rebellion comprised a group of individual, armed Americans standing up against the government and its Constitutional duties. As their armed and violent rebellion grew, Washington organized a federalized militia (as the 1792 Militia Act authorized the federal government to do, spelling out in more detail the role of those militias mentioned in the Second Amendment) and marched west from the capital at Philadelphia, subduing the rebellion without further violence.

Washington’s choices and actions didn’t necessarily reflect the Constitution’s or the amendment’s original intentions, as no subsequent moment necessarily can (nor, indeed, can we know those intentions with any certainty). But they remind us that the well-regulated militias the Second Amendment seeks to guarantee played a central, federal role in this Early Republic period. These collected bodies of armed Americans were an integral part of the nation’s government and defense, one that continued to serve as America’s primary military force until at least the turn of the 19th century. Which is to say, the Constitution’s guarantee of the “right to bear arms” was, like every other element of the Constitution, directly tied to governmental and legal structures, linking individual rights to those collective, national necessities.

Many things have drastically changed in America since the 1780s, including of course the types of guns and weapons that are available to individual Americans (rather than simply for use by our armed forces), and the damage those weapons can do in a terrifyingly short time. Those contexts too must be part of our 21st century conversations, and of our legal and political definitions of “well regulated” and “Arms” at the very least.

But at the same time, some core Constitutional issues remain similar to what they’ve always been. One of them is the Constitution’s emphasis on collective identity and needs, on how “we the people” can “establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense [and] promote the general Welfare” while still “securing the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.” I’m not sure any communal experience reflects more clearly our frustrating current distance from those goals than horrific, ubiquitous school shootings. Doing everything we can to end that trend is as Constitutional as it is crucial.

Featured image: Daniel Boone escorting settlers through the Cumberland Gap. Painting by George Caleb Bingham, Washington University in St. Louis, Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum / Wikimedia Commons)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thanks for the question and thoughts, B. Daniel. Certainly those issues are part of the whole addition of the Bill of Rights, especially in the 10th Amendment’s focus on the states but also in the Bill’s overall relationship to the Constitution’s focus on the federal government.

I would add that whichever way we read “State” in this particular phrase (and my personal reading would still be more along the lines of “Government,” as in “head of state” and the like), the emphasis would remain on the collective and governmental need for these citizen militias.

Thanks,

Ben

Mr. Railton,

“A well-regulated Militia being necessary to the security of a free State,” I’m focused on the word state.

Did the founders mean the individual 13 states, not the federal government? In other words was the founders intent to arm citizen militias to protect themselves and their states from an overly powerful federal government? The Civil war was fought partially over state rights vs Federal rights. I suspect that in the late 1700’s having just fought a war against a powerful, far away government that our founders would be reluctant to create a similar imbalance of power between states and federal governments.

Thanks for the comments, all. Mr. Scott, a couple quick things:

1) The Supreme Court has also found, among other things, that enslaved African Americans were not people, that racial segregation was Constitutional, and that Japanese internment was likewise. The Court isn’t infallible and its rulings can certainly be challenged and evolve over time.

2) Hamilton’s Federalist 29 does explicitly address the concept of well-regulated militias as a Constitutional goal. I believe that Federalist Paper supports my arguments here.

Thanks,

Ben

These people using guns to murder people come from homes that never teach their children anything whatsoever about God. We live in a Godless society and parents are not teaching their children right from wrong. It is what is in a person’s heart that makes a person kill. Not guns, a ungodly heart.

The U.S. Supreme Court explicitly found the Second Amendment a right of and for the individual, not collectivist. The Federalist Papers is a ready source to find the original intentions of authors of the Constitution. This article has so many propagandist errors in it the editor should be ashamed.

Thanks for this timely, well researched feature Professor Railton, and the helpful links. Someone was just saying to me earlier this week that it’s strange we haven’t had any school shootings in a while, although I know there have been a few (planned) ones that were fortunately neutralized in the nick of time.

Any individual determined to get military-type assault weapons to kill as many people as quickly as possible (which increasingly seems to be the goal) is now a never-ending nightmare. Much of the blame has to go to the toxic entertainment industry over the past 30 years, glorifying carnage and fires in video games and the endless film equivalents.

While it’s true that it won’t cause/influence 99% of people to commit these crimes, a fraction of 1% can, and continues to do a lot of damage. Before these elements were standard crutches in “entertainment” horrific shooting were very rare occurrences by comparison. Saying the entertainment industry has no blame in this on-going nightmare is like the tobacco industry saying cigarettes have never played a role in the millions of lung/throat cancer deaths over many decades, or vaping is a STILL a safe alternative.

It’s too late to do anything about the destructive entertainment industry now. Unfortunately, everything they do falls under ‘freedom of speech’. Children and would-be arsonists are encouraged to start “Playing With Fire–0% Containment” because some influential rich @#*%#(&$ thought THAT was a great idea for a comedy. Arson fires, like mass shootings, have skyrocketed over the past 25-30 years. No shock there.

I don’t know what can be done regarding America’s gun crisis other than adopting the policies of most nations around the world that do not have this problem. I don’t think that’s possible, and if it were attempted there likely would be even more violence/gun violence trying to stop it. The U.S. is so divided on nearly everything with social media and the constant drama in Washington D.C. making it worse by the day. I don’t see anything but more of the same barring a miracle, literally.