One of the abiding questions of American history is “Why did Americans ever vote for Prohibition?”

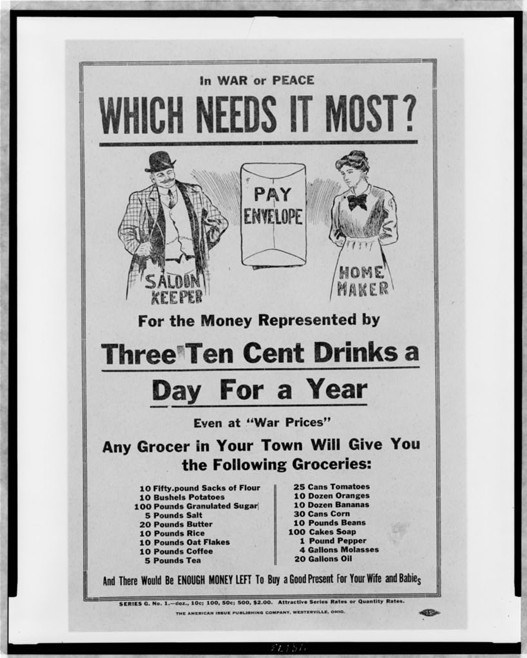

The original reason was obvious. They could see alcohol destroying the health, careers, and income of too many people, often leaving their families destitute. While that wasn’t reason enough for the government to prohibit alcohol, it didn’t stop temperance organizations from trying to keep people from using it and saloons from serving it.

Saloons were plentiful in urban America; in 1909, there was one for every 200 people. But they had an evil reputation. Many were crime-infested hovels, neighborhood centers for gambling, prostitution and violent gangs.

The Women’s Christian Temperance Union was formed in the 1870s to encourage men to give up liquor. The women kneeled outside saloons and prayed in the street in hope of touching the conscience of drinkers inside. After decades of such efforts, Prohibition had gained little ground. Proponents realized only the law could end the liquor trade.

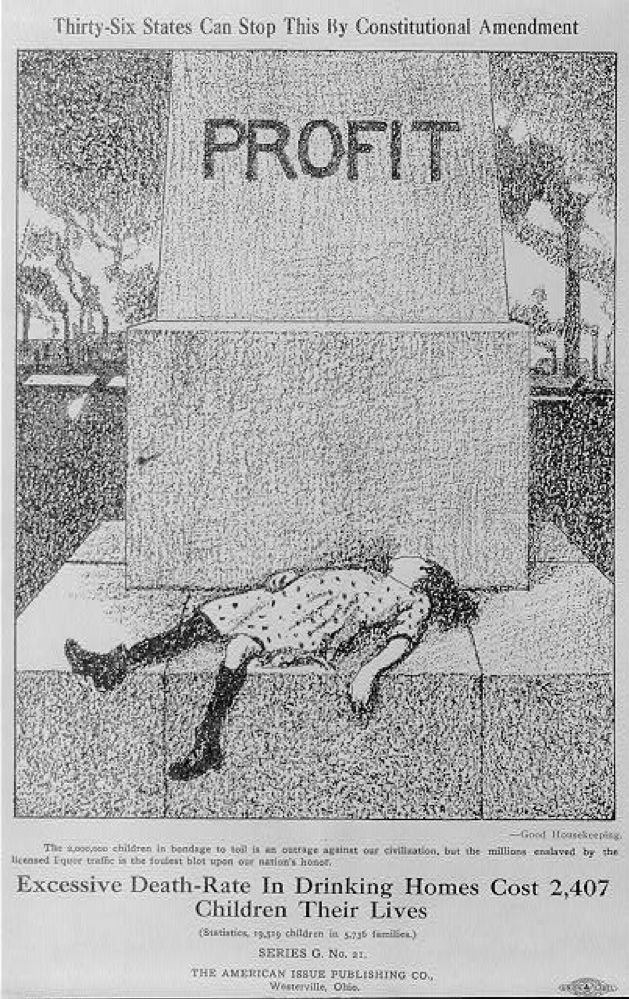

In the 1890s, the Anti-Saloon League was formed to push for anti-liquor laws at the state and national level. By the 1910s, it had become strongest lobbying group in Washington as it attacked both liquor and the establishments that served it.

The League realized it had to come up with practical arguments to convince legislators to outlaw liquor. Recent events had already provided several reasons. The federal government had long supported itself with an excise tax on liquor. But in 1913, this revenue was replaced by individual income taxes. The budget no longer depended on the sale of alcohol.

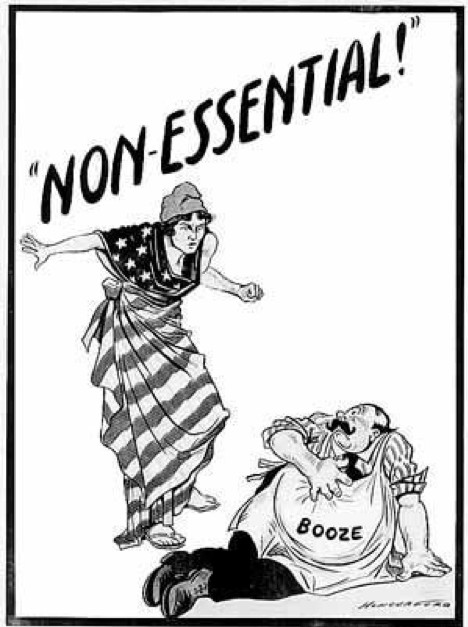

Grain used in distilling and brewing was now needed to feed its soldiers now that the U.S. had entered the world war.

Prohibitionists now added several more arguments.

The major breweries were owned by German immigrants or German-Americans, any of whom, the prohibitionists argued, could be secretly working for the German government. Beer was called “the Kaiser’s brew.” The head of the Anti-Saloon League said, “a number of breweries around the country are owned in party by alien enemies.” Wisconsin’s lieutenant governor said, “We have German enemies in this country… the most treacherous, the most menacing, are Pabst, Schlitz, Blatz, and Miller.”

Advocates also claimed America would gain a sober, responsible, productive workforce once alcohol was taken from workers. Businesses liked the idea of sober workers, who’d be more diligent and honest. They also saw a chance to reduce worker’s compensation due to liquor-related accidents.

The armed forces had already embraced the benefits of sobriety. Believing it essential to the strength and morale of America’s soldiers, the government outlawed all intoxicating beverages within a five-mile radius of army camps.

Sensing growing support across the country, many advocates began promising highly optimistic results. Economists predicted a more prosperous nation. Churches promised higher morals and a more honest, even virtuous, citizenry. The histrionic evangelist Billy Sunday said, “The slums will soon be only a memory. We will turn our prisons into factories and jails into storehouses.”

Some towns were so confident of the coming redemption of their citizens that they sold their jails.

According to an October 4, 1919, Saturday Evening Post article, “Doings in Dryland” by Samuel G. Blythe, prohibition was already raising the quality of life for Americans in unexpected ways.

In Los Angeles, where prohibition was already in force, a barber told him that since he’d stopped drinking he had more money to spend on the family and the house. He’d repainted his home, wallpapered some rooms, and bought a piano for his daughters. And he’d wiped out all his debts.

The manager of one of the city’s biggest hotels said that prohibition had originally cut into his revenues but they had returned to their old level. Also, there was better discipline in his employees and better behavior among his guests.

In San Francisco, hotel owners found receipts from their ballrooms and restaurants increasing. Newspaper circulation numbers had gone up. A saloon had been successfully converted into an ice cream parlor.

The dry future seemed bright, as Blythe saw it, which might have led him into overconfidence. For one thing, he said New York would go dry, whether or not New Yorkers liked it. They might “consider themselves the premium Americans,” but prohibition was now the law and they’d have to obey it.

New York, of course, took its own wayward path. It became a center for smuggling and serving alcohol. In his book, Supreme City, historian Donald L. Miller wrote there were 32,000 speakeasies in New York in 1927.

Blythe also said Americans would eventually accept prohibition and it would cease to be an issue. “We are an adaptable race, and though many will not admit it as yet we’ll get used to prohibition just as we have got used to many other reforms — not like it, it may be, but accept it and adapt ourselves to it.”

America didn’t adapt. And prohibition didn’t bring prosperity. The entertainment industry went into decline. Restaurants failed when deprived of alcohol sales. Thousands of workers in the liquor industry lost their jobs. Instead of improving American morals, prohibition corrupted law-enforcement officials and grew organized crime into a vast industry. Chicago mobster Al Capone raked in $60 million untaxed dollars annually. In his policy analysis of Prohibition, Mark Thornton found that reported crime in 30 major cities jumped 24 percent in the first year, and the murder rate shot up 78 percent.

Individual income taxes gave the federal government an alternative to liquor excise taxes, but states didn’t have that option. Prohibition wiped out 75 percent of New York state’s revenue.

Prohibition actually did reduce drinking in America. When it was repealed and Americans began drinking again, alcohol consumption was less than half of what it was in 1919.

It wasn’t until the 1970s that per-capita alcohol consumption rose above its pre-prohibition level.

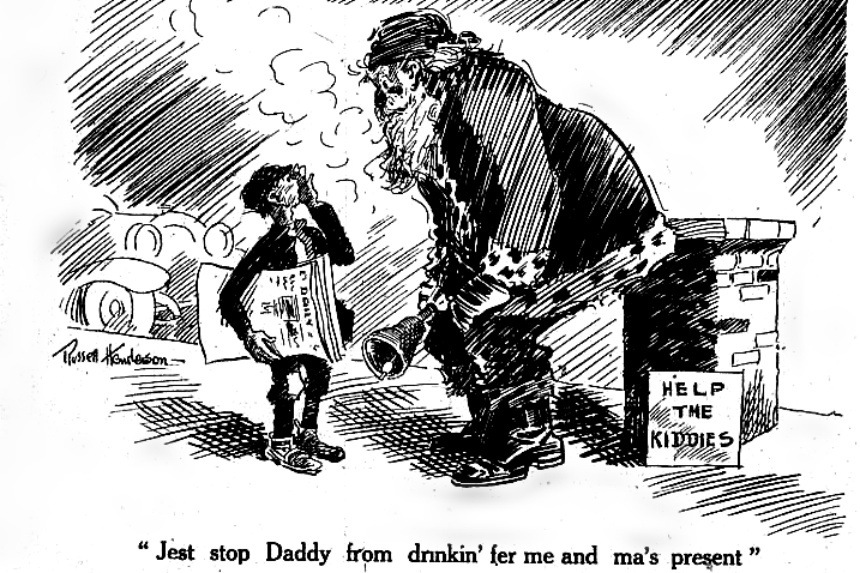

Featured image: Anti-Saloon League cartoon by Russell Henderson, 12/23/1916 (Anti-Saloon League Museum, Westerville Public Library)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now