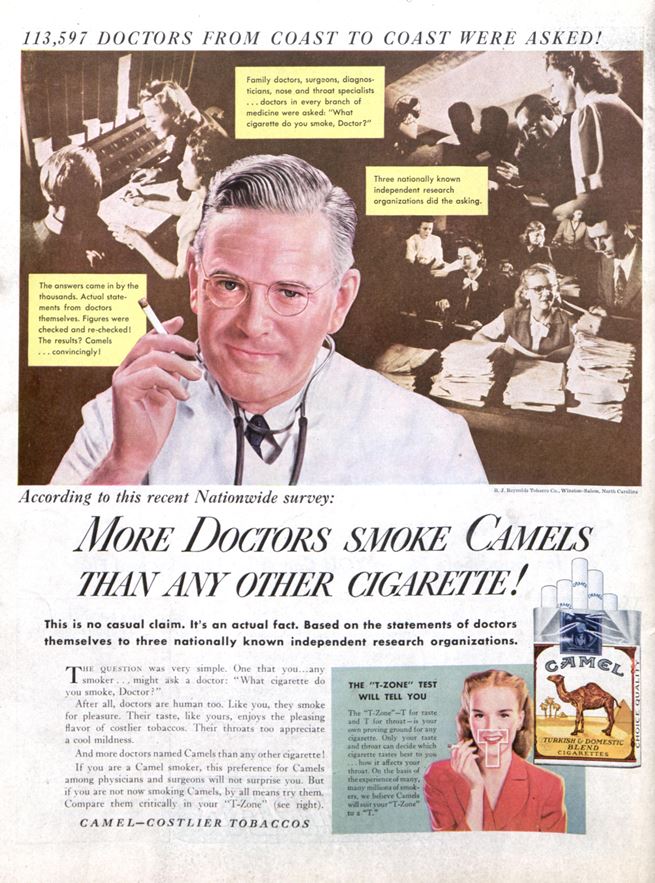

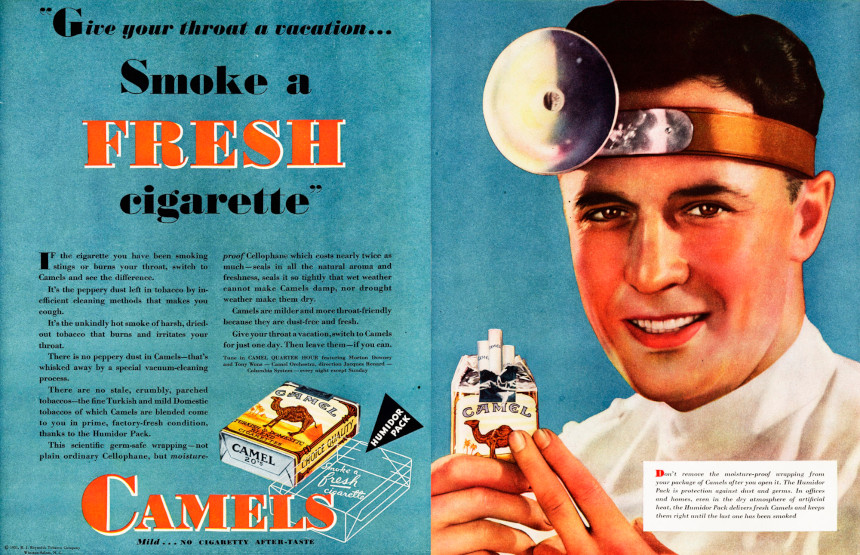

In 1946, R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company began making a bold claim in their advertisements: “More doctors smoke Camels than any other cigarette!” An ultra-specific statement in passive voice dangled above to back up this “fact”: “113,597 doctors from coast to coast were asked!” A revised version might have read “We asked 113,597 doctors from coast to coast!” Or, more accurately, “We asked 113,597 doctors from coast to coast after bribing them with free Camels!”

R.J. Reynolds’s “more doctors” ad campaign was published in most national magazines for six years, and television commercials showed men in lab coats gleefully lighting up while reading thick textbooks or making house calls.

Smoking cigarettes during this time period was as ubiquitous as drinking soda pop. Although a full-fledged public health campaign against tobacco was still decades away, anxiety about smoking and its negative health effects could be found going back to the turn of the century. Big players like American Tobacco Company, Philip Morris, and R.J. Reynolds sought to soothe these fears by using advertisements to marry doctors and cigarettes in the American mind.

Otorhinolaryngologist Dr. Robert Jackler, of Stanford University, and his wife Laurie founded the group Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising, and they compiled around 50,000 original tobacco advertisements, many of them from this magazine. The collection ranges from the absurd to the bizarre, with images of storks taking smoke breaks, cigar parents raising cigarette babies, and children smoking while their parents look on and giggle. Some of the most surreal ads, from today’s perspective, feature doctors touting the benefits of smoking certain brands. In April, Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History opened an exhibit called “More Doctors Smoke Camels” that showcases many of these American artifacts. Jackler says many museum visitors have gawked at the ads and their health claims in disbelief, but these images and their style of persuasion set precedence for all kinds of health-based advertising.

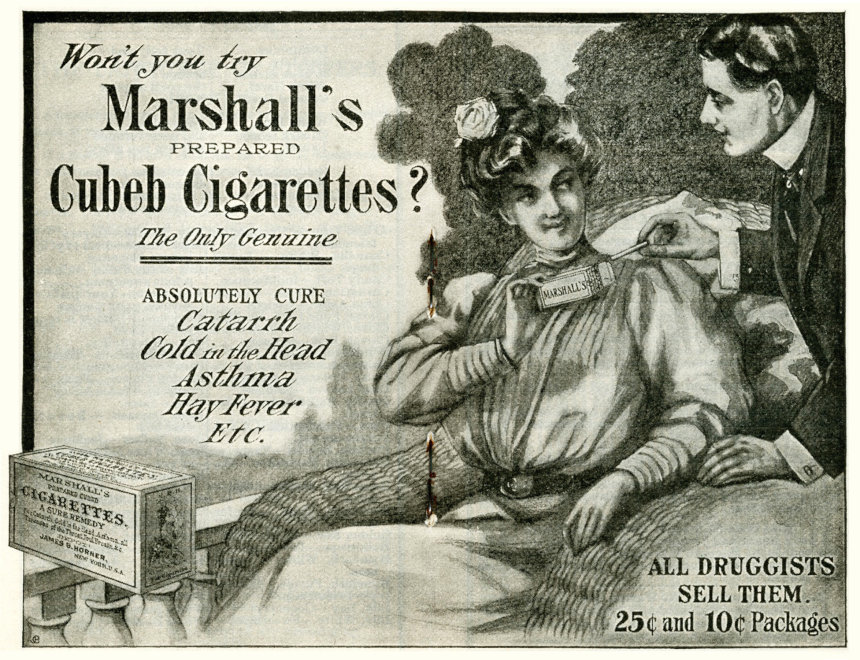

In the 19th century, it was widely believed that smoking could actually cure some ailments. For asthma, bronchitis, hay fever, and influenza, Cigares de Joy advertised “immediate relief.” Similarly, Marshall’s Cubeb Cigarettes could supposedly “absolutely cure” all of those, along with the buildup of mucus known as “catarrh.” Inhalation of smoke had long been a health concern, but well-known European doctors promoted smoking cubeb (tailed pepper), stramonium (jimsonweed), and even tobacco to ease coughing fits. These half-baked remedies coincided with the growing popularity of smoking tobacco as a signal of economic independence and masculinity.

Come the 1900s, everyone seemed to be picking up the habit.

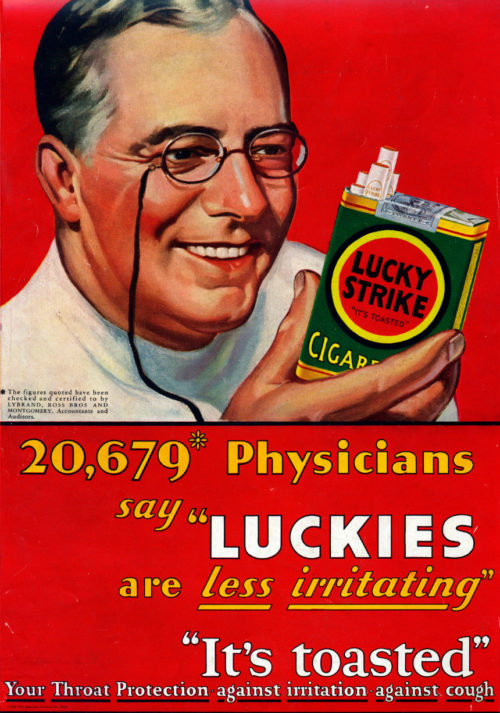

In 1930, Lucky had first made the claim that “20,679 physicians say ‘Luckies are less irritating’” on an ad with a smiling doc offering up a pack of the most popular smokes of the time. American Tobacco Company (the maker of Luckies) hired the advertising firm Lord, Thomas, and Logan to mail cartons of cigarettes to physicians in 1926, 1927, and 1928 with a survey asking whether “Lucky Strike Cigarettes … are less irritating to sensitive and tender throats than other cigarettes.”

In the decades to come, newcomer Philip Morris would claim that their cigarettes were scientifically proven to be less irritating as “eminent doctors report in medical journals.” The company insisted their addition of diethylene glycol — a poison — into their tobacco made it moister and better on the throat, and they sponsored researchers to find as much. In reality, the foundation of their claim was an experiment in which two Columbia University pharmacologists injected the chemical into the eyes of rabbits. Other researchers disputed their results.

Along with its “More Doctors Smoke Camels … ” claim, Reynolds also pushed the idea of the “T-zone test” (for taste and throat), illustrated by a T-shape superimposed on a woman’s smiling face. The diagram was reminiscent of something you might see on a poster in an otolaryngologist’s office. This came years after what Jackler called “perhaps the strangest claim in all of tobacco advertising history”: R.J. Reynolds insisted their cigarettes helped speed digestion by increasing alkalinity (“For digestion’s sake, smoke Camels!”). A 1951 FTC cease-and-desist order prohibited the company from making such claims, but that ad campaign had come and gone.

Two years ago, Dr. Jackler released a paper on a lesser-known advertising strategy of the tobacco industry from the 1930s to the ’50s. In order to court doctors directly, tobacco companies took out ads in most weekly and monthly medical journals, and particularly the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). Since advertisements were often scrapped before the journal’s archives were bound, many of these ads were forgotten, but Jackler’s team compiled more than 500 of them. “Not one single case of throat irritation due to smoking Camels!,” a 1949 JAMA ad reads. “Put your stethoscope on a pack of Kools and listen,” a 1943 ad beckons. Philip Morris flirted with absurdity in a 1942 ad emblazoned with the suggestion “What! — Prescribe Cigarettes?”

“Even though more and more data was coming out about lung cancer and eventually chronic lung disease and heart disease, so much money was coming to medicine journals [from tobacco companies], particularly JAMA,” Jackler says. In 1949, the AMA received 33 times more income from JAMA’s advertising than from membership dues.

According to Dr. Jackler’s paper, JAMA’s editor-in-chief (from 1924 to 1949) Morris Fishbein made a slow transformation from tobacco critic to consultant over the course of his career. In the late ’20s and early ’30s, Fishbein authored books and editorials criticizing cigarette advertising and the medical industry’s advertising practices more broadly. Fishbein developed a relationship with Philip Morris, however, that evaporated his skepticism in the years to come. He maintained correspondence with the company to help them create ads and even authored an editorial defending their use of diethylene glycol after 75 people died from poisoning in 1937. Fishbein ruled the journal with an iron fist throughout the ’40s, squashing dissent against its advertising practices and even ignoring calls from the board of directors to rein it in. When the protest of physicians against tobacco advertising in JAMA grew too large, the journal finally ceased publishing tobacco ads in 1954. The same year, Fishbein took a job with Lorillard Tobacco Company, making the equivalent of about $240,000 a year in 2019 money. As late as 1969, Fishbein publically doubted the link of cigarettes to cancer, calling it “a great propaganda.”

Tobacco ads on television and radio were banned in 1971, and the Master Settlement Agreement in 1998 curtailed other forms of tobacco advertisement. Tobacco companies can still advertise in print publications, although there are far more restrictions for those today. Health claims are out of the question.

A study on tobacco advertisements in magazines in Preventive Medicine found that cigarette ads increased more than threefold in publications like Rolling Stone, Star, and Entertainment Weekly from 2010 to 2014. Of course, e-cigarette advertisements have also taken off in recent years. It is possible to grab a magazine in a doctor’s office waiting room and find a full-color ad spread that calls attention to the “experience” or “taste” of tobacco, but the chance remains unlikely that we will ever again see any featuring the doctors themselves. The 1.95 percent of doctors who do smoke — according to JAMA’s latest numbers — aren’t likely to flaunt it anyhow.

Featured image: P. Lorillard, 1938 (Courtesy SRITA)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Re: Sandra

“So they banned smoking from tv ads and started pushing alcohol, adultery, fornication, glorifying drug use and unjustified killings, displaying women as sex objects, teaching young people to be disrespectful of parents, all elderly, and those in authority. Some trade off.”

There’s nothing wrong with “fornication” – We as a society are much happier with it being legal. Now, as for “teaching young people to be disrespectful of parents”, usually most parents/elderly do deserve respect, but they’re just humans, not gods, and that should be recognized. Thirdly: “displaying women as sex objects” is nothing new (see ads from the 1940s/1950s) and now that men are displayed as such too, it’s OK. “glorifying drug use” – depends on which ones. Cocaine/heroin are no-nos. “adultery” is still recognized as wrong, but something no DA will prosecute. Lastly “pushing alcohol” is nothing new. If anything the push for weed will reduce alcohol.

When in college, cigarette companies paid regular visits to campus and distributed free tobacco, usually in 4 or 8 packs! That’s how I got started.

Our government has recommended that no one smoke since it is harmful to health. But no one seems to be interested in the growing amount of woodsmoke in our air, especially in the western states, from huge numbers of wildfires as well as the prescribed burns being ignited to mitigate them. The particles making up woodsmoke are incredibly light letting them travel far away from the burn site. They are also incredibly tiny, only .01mc. When these particles are inhaled they go deep into the lungs where the body can’t easily remove them. Firefighters, the elderly and children are at the most risk, but the rest of us air breathers, even those far from a burn site are affected. I predict that in 20 years we will have a lung cancer health crisis similar to the problems caused by cigarettes as those who are breathing in woodsmoke now find out the terrible consequences.

One brand advertisement said with their cigarettes “There’s not a cough in a carload!” Lucky Strikes add “LSMFT”, Lucky Strike means fine tobacco!”

I like to sit in a shady area to do my exercise here at Assisted Living Facility.

There is a smoking area about 50 feet away. When someone is smoking a cigarette there I can smell it and it makes me sick so I have to move to another area. It is amazing how strong cigarette smoke it today or I am sensitive to it.

So they banned smoking from tv ads and started pushing alcohol, adultery, fornication, glorifying drug use and unjustified killings, displaying women as sex objects, teaching young people to be disrespectful of parents, all elderly, and those in authority. Some trade off.

It may be of interest to note that on February 27, 1833, the following declaration of a revelation from the Lord was announced by the Prophet Joseph Smith Jr. and promulgated by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints warning: “Behold, verily, thus saith the Lord unto you: In consequence of evils and designs which do and will exist in the hearts of conspiring men in the last day, I have warned you, by giving unto you this word of wisdom by revelation …..And again, tobacco is not for the body, neither for the belly, and is not good for man,…”

As a result of that revelation, members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, who observed faithfully the Lord’s council and avoided the use of tobacco, were significantly less impacted by the horrors and suffering sustained by people who became addicted to tobacco products.

That was the Kool Aid of yesteryear now it’s Global Warming

From the time I was a child, I was warned that cigarettes were unhealthy. Since then I have lost two very dear friends to lung cancer, after years of struggling with COPD. I don’t understand how so many people missed the warnings, unless they simply didn’t care what they were doing to their bodies. It seems we are always more interested in doing exactly what we want to do, regardless of how self-destructive it is.

Great article on a still horrible nightmare: cigarettes, smoking and all the endless lies and promises that these cancer sticks aren’t toxic. Less irritating to the nose and throat?! That sounds like ‘code’ to me for “less harmful”; something I’d want to steer clear of in the first place.

Your thorough research and fact finding here Nicholas make the whole thing that much more appalling. I can remember coming home from work in 1986 (right before indoor smoking was banned) and my suit jacket would still smell of it the next morning. I was able to tolerate it then, now I can’t stand even a whiff of 2nd hand smoke, it smells so horrible. Though not a pot smoker I don’t have a problem with the scent of it however, or being in a room with it. My concern there is the fact it’s still smoke.

Nicholas, could you find out what the cigarette companies are doing that make today’s cigarettes stink so much more, in a reply here? They used to smell, granted, but not like the out-and-out poison they do now. It has to be something to make them more addictive to the people who still do smoke to help offset their ever shrinking market and profits. Not shrinking enough though! HATE smelling it by accident innocently walking through a parking lot, or right outside a store entrance or exit. Please review and advise. Thank you.