This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Last week, nearly 50,000 members of the United Auto Workers union went on strike at General Motors factories across the country, one of the largest national strikes in decades and part of a larger trend toward significant labor actions. And in a few weeks, Netflix will premiere director Martin Scorsese’s much-awaited new film The Irishman, which stars legendary actors Robert De Niro and Al Pacino in a historical drama depicting controversial labor leader Jimmy Hoffa and his ties to organized crime in mid-20th century America. These events are bringing renewed attention to different sides of the American labor movement.

While Hoffa was only one figure, and his historical legacy has perhaps been overstated due to his still-mysterious disappearance, Scorsese’s film reminds us of a central element to the 20th century labor movement: its status as a racket. It’s impossible to tell the story of American labor over the last 100 years without engaging that side of the story, not just through overt aspects like the relationship to and role of organized crime but also through labor leaders and organizations that have themselves operated much like mob bosses.

Yet like Hoffa’s larger-than-life legacy, those aspects of the labor movement can be given too prominent a place in our collective memories — and in so doing, we risk forgetting the truly radical origins of the labor movement in America, legacies that importantly contextualize today’s national strikes.

The 1877 railroad strikes, which are generally seen as the first such national such labor actions, exemplify those radical origins. Strikes had been part of American society since its first European settlements, with Polish craftsmen in the Jamestown colony striking for fair treatment and civic rights in 1619. As early as 1648, Boston coopers and shoemakers both formed workers’ guilds to advocate for workplace standards and practices. But for the next two centuries, both labor organizations and labor actions would remain largely at the local level, achieving advances in their particular communities but not uniting larger cohorts of American workers in service of shared, societal goals.

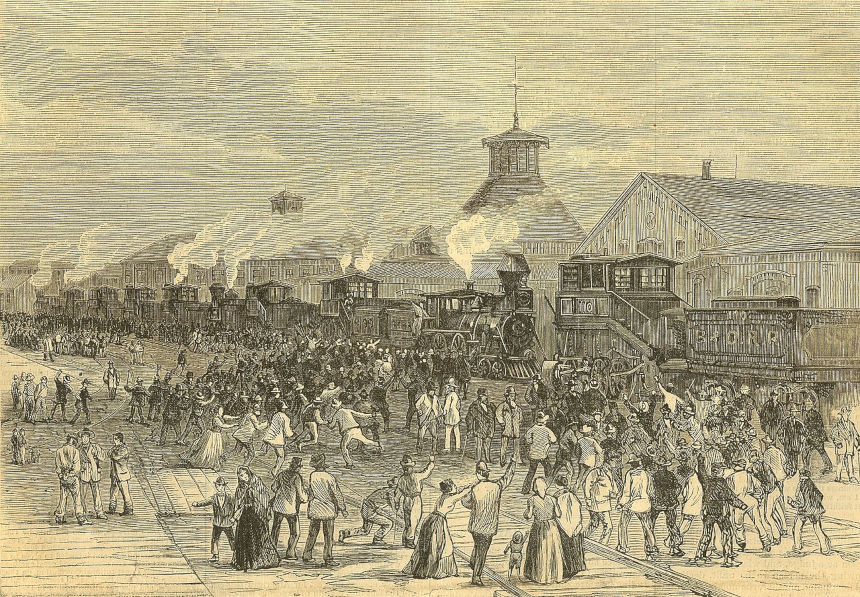

The 1877 strikes would bring labor organizing and activism to the national stage. They began on July 14 in Martinsburg, West Virginia, where the Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) Railroad had cut its workers’ wages for the third time in a year. In response, striking workers stopped all train service in the city. Governor Henry Mathews sent in the state militia to end the strike, but the soldiers would not fire on the strikers and the labor action continued. It soon spread to other mid-Atlantic states, with the first follow-up strikes in the Maryland cities of Cumberland and Baltimore, as well as a more violent clashes between the militia and strikers in that latter city. By the end of July strikes and violence had reached Albany, Pittsburgh, Scranton, Chicago, and East St. Louis, among other cities.

The combination of widespread, sustained labor actions and extreme, violent responses led these 1877 events to be known collectively as the Great Upheaval, and both elements reflected the moment’s profound radicalism. The strikers wanted to achieve their immediate goals (such as wage guarantees and increases), but also advocate for broader, systemic changes that would affect workers across the nation and in every industry. That is, even while they fought for their lives and rights, the 1877 strikers, organizers, and labor leaders also advocated for issues like child labor laws, health and safety regulations, and the 8-hour workday.

The consistent use of troops and violence to respond to the strikes likewise reflects the moment’s truly revolutionary nature. Like Governor Mathews in West Virginia, the authorities in each affected city and state called out not just police but also state and volunteer militias (as well as private armies like the infamous Pinkerton detectives); and unlike in Martinsburg, in far too many cases those units did not hesitate to use lethal force. When those local and state forces were unable to stop the strikes, President Rutherford B. Hayes went one step further, sending federal soldiers to each city in order to suppress both the violence and (especially) the labor actions themselves. These nationwide clashes between American soldiers and rebels could be accurately described as a brief but brutal period of revolution or civil war that reflected the moment’s profoundly radical nature and effects on American society.

Beyond those violent repercussions, the effects of the 1877 general strike were both immediate and long-lasting. On May 1, 1880, the B&O Railroad company established the Baltimore and Ohio Employees’ Relief Association, a groundbreaking example of worker insurance and protection; four years later, the company offered one of the first corporate pension plans in American history. On a broader scale, the national labor movement grew exponentially in the years following the strikes: the Knights of Labor, the first truly national union, grew from a few thousand members in the 1870s to 28,000 in 1880 and roughly 700,000 by 1886 (with many members also separating to form the American Federation of Labor); and the 1880s as a whole would witness more than 10,000 strikes and labor actions, as this form of radical activism became a commonplace part of American society.

Yet to my mind, despite such prominent effects neither general strikes nor violent clashes reflect the labor movement’s most radical elements. Instead, I would emphasize the ways that movement represented a diverse coalition of American workers. Too often, the movement relied upon hierarchies or discriminations, such as the late 19th century American Federation of Labor (AFL)’s use of the category of “skilled labor” to consistently exclude immigrants and African Americans.

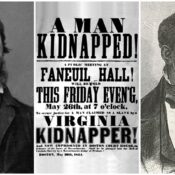

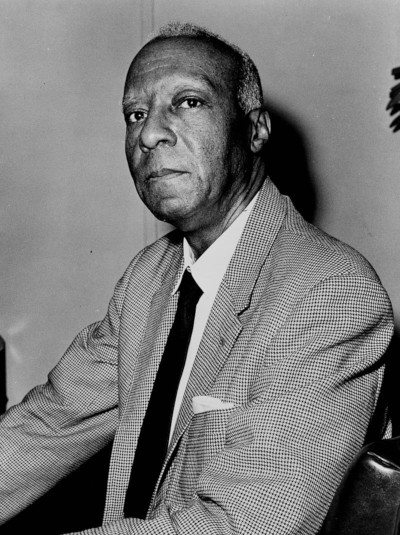

Instead, labor leaders of color helped actively resist discrimination and model an inclusive labor movement. A vital case in point is the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), the first labor organization led by African Americans to receive an AFL charter. African-American Pullman porters had comprised the vast majority of that workforce since the railroad company’s late 19th century origins, and Pullman remained one of the nation’s largest employers of African Americans into the 1920s. Porters had tried unsuccessfully to organize for years, but in August 1925 a group of more than 500 met in Harlem, formed the BSCP under the slogan “Fight or Be Slaves,” and chose New York labor organizer A. Philip Randolph (previously co-founder and president of the short-lived African-American union the National Brotherhood of Workers in America) as their first president.

Powerful figures like Randolph and his BSCP co-founder (and first vice president) Milton Price Webster, a Chicago political leader in the era’s “black Republican machine” as well as a lifelong labor activist, represent a key contrast to more corrupt labor leaders like Jimmy Hoffa. Randolph and Webster certainly ruled the BSCP throughout its early years, quickly turning it into a national powerhouse that by 1929 received affiliated status from the AFL. But they did so in order to advocate for the under-represented workers and gain them a voice. Their efforts produced inspiring legacies: in labor activism, as illustrated by Pullman’s ground-breaking August 1937 contract with the BSCP; and in civil rights, as Randolph in particular would become a leading voice in the nascent Civil Rights Movement, as exemplified by his June 1942 Madison Square Garden address to an audience of nearly 20,000 African Americans, a speech that launched the era’s March on Washington Movement.

From the 1877 general strikes to that 1940s activism, and up through today’s UAW actions, time and again the labor movement has represented a radical force in American society, politics, and culture. While we can’t ignore the darker sides to the movement, whether its discrimination or its links to organized crime, neither can we afford to minimize that fundamentally radical legacy. Not if we want to understand our histories, and not if we want to move forward into the kind of fair and equal society that the labor movement can help us create.

Featured image: The Sixth Maryland Regiment confronts striking workers in Baltimore (photo by D. Bendann, Harper’s Weekly, August 11, 1877, Library of Congress)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now