“It was like Moses parting the seas.” That was how one eyewitness described the scene. By 2010, Comic-Con San Diego had ballooned from its humble 1970 origins into the massive carnival it is today, with tens of thousands of conventioneers dressed as their favorite heroes and heroines, each hoping to play the latest video game, handle exclusive merchandise, maybe catch a glimpse of an A-list star. Yet in all the chaos, the countless Batmen, Wonder Women, and stormtroopers parted to make way for the biggest name in the building. Over a thousand people would cram into the conference room where he would field questions.

He was no hot young actor or starlet, nor a director of the latest comic book to get a film treatment. At almost 90 years old, Ray Bradbury could only smile as his wheelchair was pushed through the parting throng of gushing, gawking fans.

The scene in 2010 was different from the one in 1939 at the great-granddaddy of all cons, The World Science Fiction Convention in New York. Bradbury, then only 19 years old, had to borrow money from his good buddy (and, later, his literary agent) Forry Ackerman to ride a Greyhound across the country and stay at the local YMCA. At this gathering, the teen rubbed shoulders with the likes of Isaac Asimov and John W. Campbell, editor of Astounding Stories of Super-Science and a leader in the burgeoning science fiction genre, but ultimately failed to sell any of his stories to the numerous publishers he visited.

Thirty-one years later, Bradbury was asked to speak at a new conference venture in San Diego. In 1970, all of 300 people attended the Golden State Comic-Con, as it was then known, and no one knew that it would soon evolve into a world-famous annual comic event, known simply and without need of explanation as Comic-Con. Bradbury was well-established in the world of science fiction and fantasy by then, having published the modern classics Fahrenheit 451 and The Martian Chronicles, the former already a mainstay of high school English classes.

There was only one reason for someone as successful and well known as Ray Bradbury to attend a tiny gathering that the rest of the world ignored: He just loved comics. As he later said of his childhood comics, “Without all this splendid mediocrity, this sublime and wondrous trash in my background, I don’t think I would be any sort of writer today.” Comics created Bradbury, and in turn he propelled the medium forward.

Other writers had seen their works illustrated, but it was Bradbury who first embraced comic books and respected them in a way more easily understood in today’s Internet-based culture. He envisioned graphic novels decades before they existed, defended comic books at a time when they were being burned in public, and supported Comic-Con from that first gathering in 1970 through the end of his life. He never cared whether what he liked was trendy or cool; he simply did what he loved.

The World the Children Made

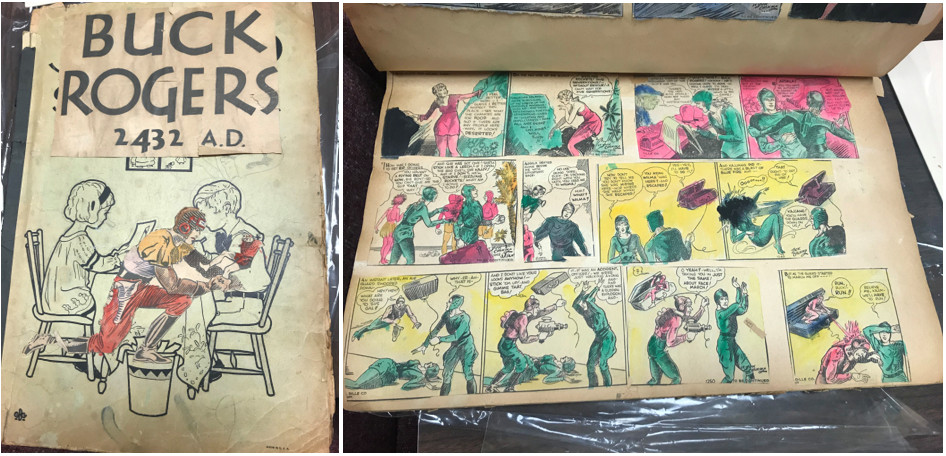

As a boy growing up in Waukegan, Illinois, a city he would immortalize as Greentown in Something Wicked This Way Comes and Dandelion Wine, Bradbury obsessively scrapbooked his heroes from the newspaper comic strip pages. These included the wonderfully illustrated worlds of Phil Nolan and Dick Calkins’ Buck Rogers, Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon, and Hal Foster’s Tarzan and Prince Valiant. Hal Foster’s art depicted fantasy realms in nonexistent lands. Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon were Earthmen in space who introduced an entire generation of children to faraway galaxies and literally out-of-this-world inventions. In an era when horses were still hauling blocks of ice and plenty of homes went without electricity, these cartoons predicted a world of rocket ships, ray guns, and jetpacks. While science fiction was starting to pop up in movies, it was the funnies that brought the genre daily to the masses. They also planted the seed in a boy’s mind that sprouted one of the most prolific fantasy and science fiction careers of the 20th century.

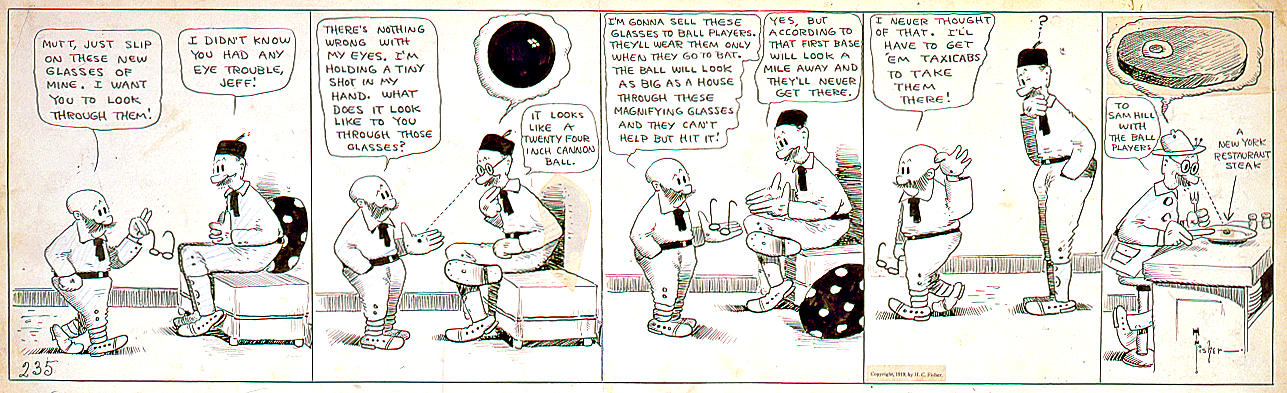

In the late 1920s and early ’30s, there were no comic books per se. Occasionally a publisher would release a bound volume of Mutt and Jeff or Bringing Up Father, but the roughly 8-x-10-inch comic books selling for a dime at the local newsstand would not come into being until Famous Funnies debuted in 1934, edited by Max Gaines. Indeed, knowing that children kept the funny pages and threw out the rest of the paper convinced Gaines that comics could be sold directly to consumers.

Starting in 1929, Bradbury created his own comic anthologies from newspaper strips, cutting out his favorites from the Waukegan News-Sun and the Chicago newspapers and pasting them into scrapbooks, sometimes adding his own artistic flair by coloring them himself. He did this with religious devotion every day for years, pausing only briefly as a nine-year-old caving to peer pressure. As he explained decades later in a piece published in the guide to San Diego Comic-Con 1980, “Kids made fun, I took on embarrassment, and tore up the strips. A month later, empty, I burst into tears, asked myself what was wrong. The answer: Buck Rogers was gone, and life not worth living.” He soon began collecting again and never looked back. Moreover, he learned to never care what the world thought of his “low-brow” tastes. As an adult, he not only kept his collection of childhood strips —24 of his scrapbooks are still intact at the Center for Ray Bradbury Studies in Indianapolis — but he would defend comics at a time when they were neither hip nor valued as art.

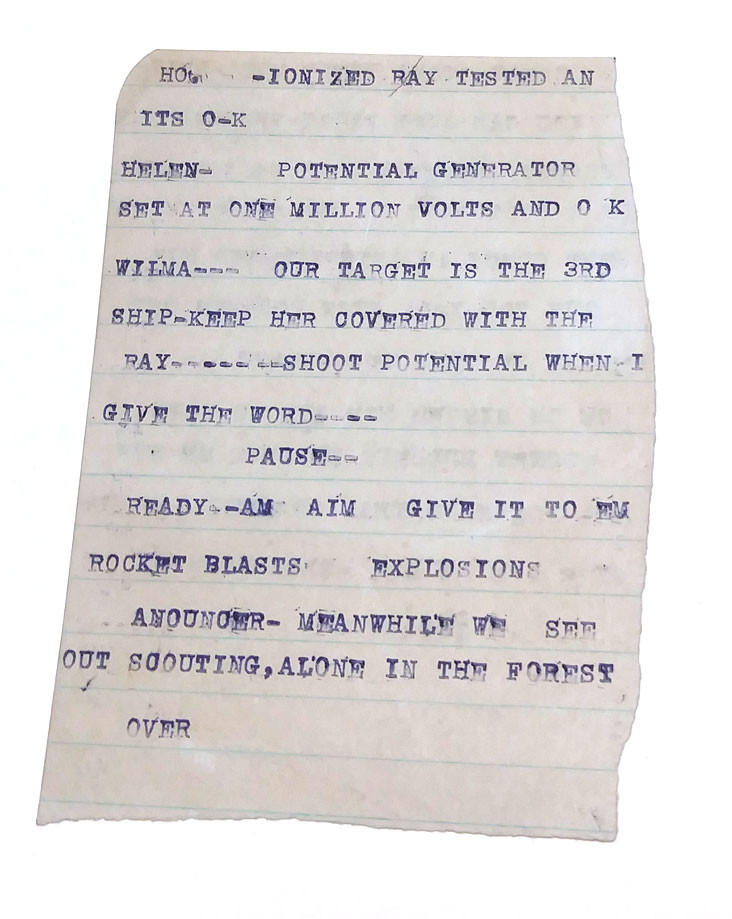

Strictly speaking, the first time the comics industry paid off for Bradbury was in 1932, when the future writer was a mere 12 years old. His family had relocated to Tucson, Arizona, and Bradbury found work as an errand boy at a local radio station. A bold child, Bradbury walked to the studio of KGAR and asked for a job. Radio shows like Chandu the Magician were another joy of Bradbury’s childhood, and dozens of his stories would later appear on radio classics like Lights Out and X Minus One.

KGAR employed the boy to empty out ashtrays and fetch food for the men. After two weeks acting as their gofer, the workers asked if he would like to be on the air. He zealously accepted. With other children, he read the adventures of The Katzenjammer Kids and Tailspin Tommy, complete with funny voices and sound effects. KGAR paid him with movie tickets, the films of Lon Chaney and Douglas Fairbanks being another love of his.

While in Tucson, the Bradburys bought their youngest a toy dial-a-letter typewriter as a Christmas gift. From the age of 12, he typed fantastic stories, including his own fan-fiction continuation of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter of Mars. Bradbury’s pre-teen writing is especially impressive when you consider how tedious the dial-a-letter typewriter was: He had to dial in and then type each letter, one at a time.

As a 17-year-old, after the family had moved to Los Angeles, Ray Bradbury joined a local science fiction club. There he met Ray Harryhausen, Forry Ackerman, and Robert Heinlein, who would become (respectively) a pioneer in stop animation visual effects; an editor, promoter, and literary agent of the science fiction genre; and “the dean of science fiction writers.” Heinlein helped the young writer get his first short story in a professional magazine, Script (the editors paid Bradbury with three free copies).

After the war, he wrote increasingly about space travel, which was becoming more likely and less theoretical as both America and the Soviet Union experimented with rockets. He speculated about interstellar travel in haunting tales like “Kaleidoscope,” “The Rocket Man,” and “I, Mars.” He rose quickly in the world of fantasy and science fiction magazines like Weird Tales and Thrilling Wonder Stories, eventually gaining a reputation as the “Poet of the Pulps.” People took notice of his talent, one of them a young comic book editor named Bill Gaines.

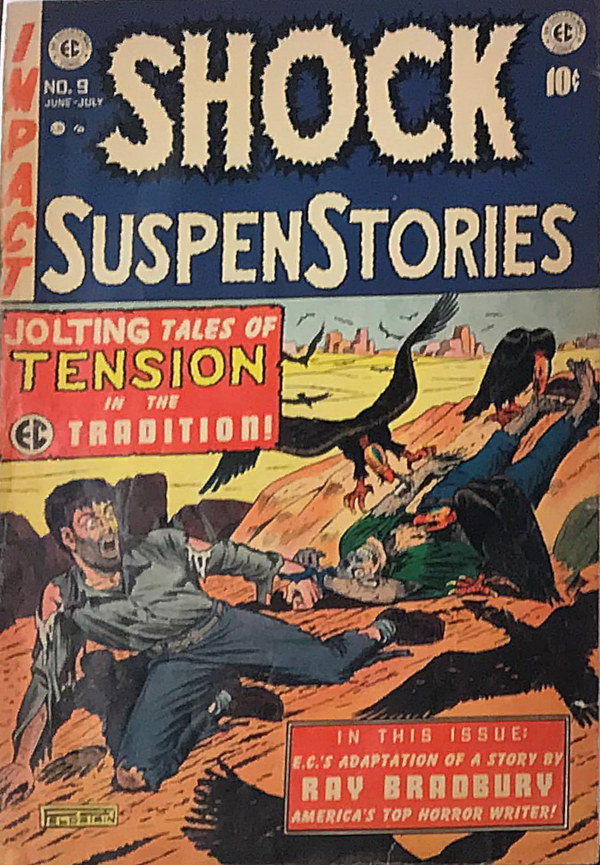

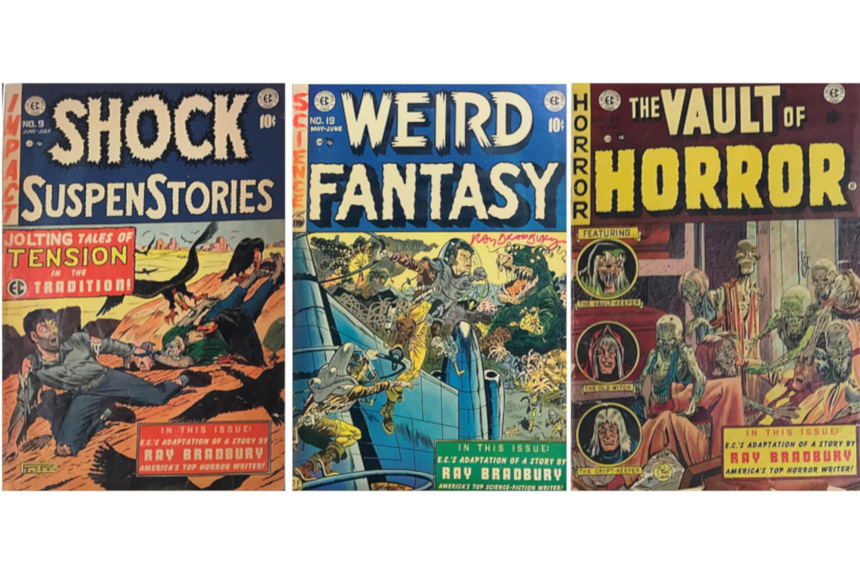

The May/June 1952 issue of Weird Fantasy, one of the many titles published by E.C. (Entertaining Comics), included the Wally Wood-illustrated story “Home to Stay,” which appeared to be based on Bradbury’s “The Rocket Man” and “Kaleidoscope.” Previous issues of E.C. Comics’ The Vault of Horror and The Haunt of Fear showcased plotlines reminiscent of two other Bradbury stories, “The Emissary” and “The Handler.” Friends and colleagues brought these stories to his attention.

Bradbury was always highly defensive of his work. He took action by sending this tactful letter to Gaines:

Just a note to remind you of an oversight. You have not as yet sent on the check for $50 to cover the use of secondary rights on my two stories. … I feel this was probably overlooked in the general confusion of the office work, and look forward to your payment in the near future.

Gaines realized it made sense to pay the writer whose star was rising in the world of science fiction. He replied in kind: “Although we do not agree with your conclusions, … we are enclosing our check for $50, without intending to agree with your contentions.”

This minor spat between Bradbury and Gaines could have ended here if not for the author’s respect for what E.C.’s team of artists had done with his works. Though in his 30s, Bradbury was still the kid from Waukegan with a basement full of newspaper strips, and he was genuinely thrilled to see his stories turned into comics. He ended his initial letter to Gaines with this coda: “PS Have you ever considered doing an entire issue of your magazine based on my stories in DARK CARNIVAL, or my other two books THE ILLUSTRATED MAN and THE MARTIAN CHRONICLES?”

At this point, these were the only three books Bradbury had published, all of them collections of short stories. The prescient writer was calling on Gaines to create something that didn’t yet have a name: the graphic novel.

Gaines passed on illustrating entire Bradbury books, but his company eventually would adapt 27 of his best-known tales, including such classics as “The Lake,” “The Sound of Thunder,” and “There Will Come Soft Rains.” In a way, E.C. Comics did create Bradbury’s graphic novels, as most of these works would later be collected in two paperbacks, The Autumn People (1965) and Tomorrow Midnight (1966). Bradbury routinely wrote letters of praise not just to Gaines but also to the artists — Al Feldstein, Wally Wood, Joe Orlando, Will Elder, and Jack Kamen.

Besides seeing his works drawn by some of the best in the business, Bradbury’s name also appeared on the covers. (“In this issue: E.C.’s adaptation of a story by Ray Bradbury, America’s top horror writer!” He was also America’s “top science-fiction writer” depending on the genre of the comic.) His was the only writer’s name E.C. Comics stamped on its covers.

But Bradbury soon asked that his name not be so prominently displayed. In the early ’50s, comics were considered at best silly, juvenile, and not worthy of “real writers.” At worst they were thought to poison children’s minds. In January 1953, Bradbury wrote a long, apologetic letter to Gaines, asking that his name be removed from upcoming covers of Entertaining Comics. He painfully explained that this request was purely business, not personal. He had recently “graduated to the slicks,” meaning that he was finally breaking out of the pulps of Weird Tales and Planet Stories and into more respected, better-paying titles like The Saturday Evening Post and the Truman Capote-edited Mademoiselle. His association with low-brow comics would not enhance his reputation.

The Irritated People

It may seem disappointing that Bradbury, famous for standing up for mass culture and being opposed to censorship, seemingly gave in to peer pressure, but this would be a simplistic way of thinking. Surrendering to the trends of the times would have meant simply abandoning E.C. Comics, considered by many social reformers to be the worst of the worst comic books, with their shocking covers and gory tales of death and dismemberment. Bradbury continued to work with Gaines and his stable of artists until their magazines folded; his asking they take his name off the covers was a compromise. “By all means,” Bradbury wrote, “exploit my stories and my name INSIDE your magazines, all that you wish.” Given that they paid him only $25 per adaptation (about $250 in today’s money), it’s clear that he was not getting much financially from a partnership that could only jeopardize his reputation. In our modern era, when top talents like Stephen King and Margaret Atwood eagerly turn their writing into graphic novels, it needs to be remembered that this was by no means a trendy or even wise move for a writer in conformist 1950s America. Bradbury wanted E.C. Comics to adapt his works simply out of childlike glee.

In the end, Bill Gaines and E.C. Comics found themselves in the crosshairs of one of America’s more hysterical movements: the comic-book burnings. In 1953, respected psychiatrist Fredric Wertham published Seduction of the Innocent, a best-selling book that claimed comics caused juvenile delinquency and homosexuality. In his denunciation of comic books, Wertham claimed, “Special emphasis is given in whole series of illustrations to girls’ buttocks. … Such preoccupations, as we know from psychoanalytic and Rorschach studies, may have a relationship also to early homosexual attitudes.”

By 1954, churches, schools, and respected civic organizations were leading bizarre purges, gathering children in public squares to throw their “filthy” comic books onto bonfires. The scenes must have reminded Bradbury of Fahrenheit 451, which he had just published.

Bradbury never forgot this odd episode of American history. In the introduction to Ray Bradbury Comics #4 (more on that publication in a moment), he wrote: “I was … put upon by professional psychologists and social reformers who … told us that fantasy was bad for children. … One learned professor managed to get quite a few comic books banned for many years.”

In that same issue, he added the following line to his previously published story “Usher II”: “All the tales of terror and fantasy, and for that matter, tales of the future were burned heartlessly. They began by controlling books of cartoons.”

Next Stop, the Stars

Bradbury’s career in comics continued to thrive as the industry itself grew and gained respectability. In 1970, he was asked if he would be willing to put in an appearance at a small convention happening in San Diego. The very first Comic-Con was so small that it fit in the basement of the U.S. Grant Hotel. Now called Comic-Con International: San Diego, the world’s largest comics convention attracts about 130,000 people annually. Bradbury returned to San Diego’s Comic Con every year until 2010, his declining health making the trip unfeasible. He loved the attention and happily signed autographs.

In 1972, he almost realized his dream of having his own newspaper comic. He commissioned Doug Wildey, who would create the Jonny Quest series, and his lifelong friend painter Joe Mugnaini, cover art designer for many of Bradbury’s books, to illustrate The Martian Chronicles. Bradbury had hoped for a weekly Sunday strip, but unfortunately, no distributors picked it up. Only the L.A. Times ran with it, and then it was only a three-page spread of the story “Mars Is Heaven” in the Times’ West Magazine.

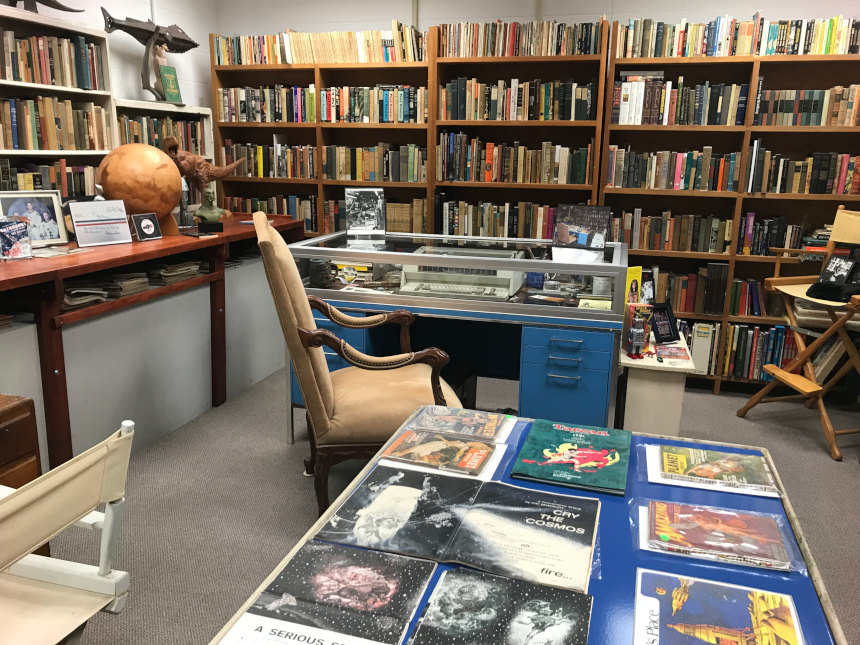

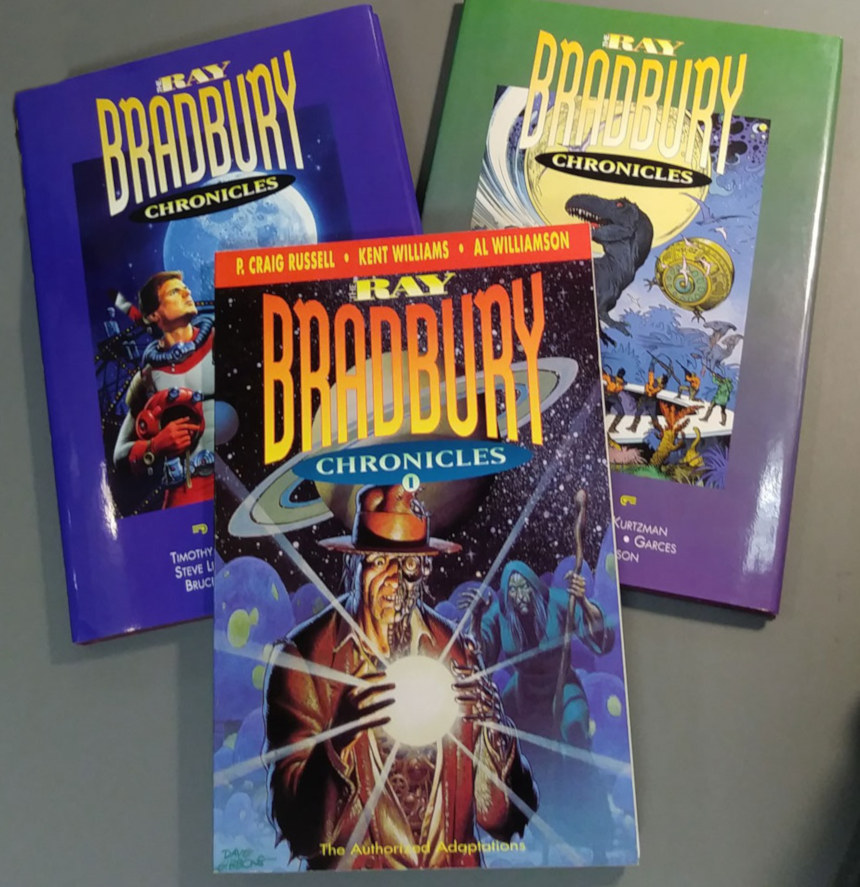

It wasn’t until the 1990s — 50 years after he first suggested book-length adaptations of his stories — that Bradbury saw this vision come true. The Bradbury graphic novels began, oddly, as the result of a video game. He collaborated with writer and software developer Byron Preiss to turn his two best-known works, Fahrenheit 451 and The Martian Chronicles, into games. Preiss next gathered a team of artists to publish The Ray Bradbury Chronicles, a limited-edition hardcover series of graphic novels of his best-known stories. This same team developed Ray Bradbury Comics, numbered issues published by the short-lived Topps Comics. While Topps will always be better-known for its trading cards, it did briefly have a comic book division in the mid-’90s, a time when many companies tried their hand at graphic novels. Each issue of Ray Bradbury Comics started with an introduction from Ray himself and included reprints from the E.C. years, plus new adaptations. This being Topps, each edition also came with three trading cards depicting scenes from various Bradbury stories.

Between 2009 and 2011, Hill & Wang published Fahrenheit 451, The Martian Chronicles, and Something Wicked This Way Comes as graphic novels. That they were published by Hill & Wang shows how much more respected Bradbury and comics had become — this was the same company that printed an illustrated version of the 9/11 report.

In 2010, Bradbury graciously accepted the Comic-Con San Diego Icon Award, granted to people who are “instrumental in creating greater awareness of and appreciation for comic books and related popular art forms.” It was a fitting tribute to a man who did so much to make science fiction and comics the respected art forms they are today, and who stood by comics at a time when many were calling for them to be outright banned.

The world can now see comics the way a little boy in Waukegan once did 90 years ago. As Bradbury once said of comics finally being accepted as art:

And anyway, it appears we are vindicated. The Pop Art people come along, late in the day, to tell us about comic strips and characters. But we send them packing. Our answer is: we knew it all the time! Don’t tell us about what we have already loved and loved well!

—from the introduction to the Autumn People, 1965

Want to learn more about Ray Bradbury’s life and legacy? Read some of his short stories that appeared in the Post, plus our one-on-one interview with the man himself in 2009. Also check out Indiana University’s Center for Ray Bradbury Studies and support the Ray Bradbury Experience Museum in Waukegan, Illinois.

Featured image: All images associated with E.C. Comics are owned and licensed by William M Gaines Agent, Inc. © 2019, All Rights Reserved.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

My brother got me the more recent Bradbury comics about a decade ago. I have loved Bradbury for years!

Bradbury is one of my favorite writers and this is a terrific piece. That photo of him with George Burns is great.