Oprah has made her picks for the best reads for the summer of 2019. So has the New York Times, National Public Radio, Quartz, actress Reese Witherspoon, Tonight Show host Jimmy Fallon, and a legion of other media outlets. With temperatures soaring into the 90s, it is peak season for summer reading.

But summer reads are hardly a new phenomenon. Name any of today’s summer reading practices — indulging in escapist beach-blanket reading, sitting poolside with a best-selling paperback, browsing that table with the label of “best summer reads” at the bookstore — and you can find these practices taking shape in the 19th century. Back then, Americans flocked to railroad cars and steamboat lines to engage in the newfound practice of summer leisure and found a selection of light summer reading waiting for them at the train station and the dockside.

The Rise of Travel, Tourism, and Summer Leisure

The story of summer reading begins with the story of American summer leisure. Taking its lead from the tradition of landscape and spa tourism in Britain and Europe, domestic tourism in the United States developed in the late 1700s around places like Niagara Falls, the Hudson River, and the Catskills. Saratoga Springs in New York state attracted those in search of the health-giving promise of its mineral springs, and Newport, Rhode Island, had attracted planters from the southern states and the West Indies with the promise of temperate summer weather.

The pace only increased in the decades that followed. By the 1830s, Ethan Allen Crawford had begun guiding travelers up Mount Washington on horseback. Wealthy Bostonians had adopted the community of Nahant, just north of the city, as a place to escape the oppressive summer heat. And by the 1850s, Maine’s Mount Desert Island and Bar Harbor had drawn artists and rusticators to the island’s rocky shores.

After the Civil War, that market for summer leisure expanded exponentially. The new wealth of the post-Civil War period broadened the customer base for lavish experiences of summer leisure — witness the appearance of the grand resort hotels along the New England shoreline and in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. So too did the expansion of the railroad. Between 1865 and 1915, the U.S. railroad network increased sevenfold, making fortunes for some of the period’s most successful industrialists and propelling, among other changes, the large-scale development of summer resorts. A promotional brochure from the early 1890s for the Poland Spring resort in Maine tells much of this story. By 1890s, Poland Spring was famous for its mineral water. It was also within easy reach of a web of major rail lines in the Northeast, including two lines from Montreal, one of which passed through the White Mountains of New Hampshire and another that connected Poland Spring to the popular resort of Bar Harbor.

The period also saw the birth of a new middle class of small business owners, government workers, white-collar clerks, and school teachers who increasingly sought summer leisure as a marker of social distinction. By 1893, the year of the Chicago World’s Fair, the summer leisure industry was so widespread that even when the editors of Appleton’s Illustrated Handbook of American Summer Resorts limited themselves to listing only the major resorts, the guidebook still included 130 different areas of note. In fact, the editors of the Appleton volume acknowledged, “There is scarcely a village or a hamlet in the New England and Middle States, twenty miles distant from a city that is not more or less visited in the summer and to this extent a ‘summer resort.’ ”

The Invention of Summer Reading

No matter how many people took to the mountains or the seashore, though, summer reading as a category was not inevitable. Light reading — reading for pleasure rather than instruction — was suspect. Warning his congregants about the dangers to their immortal souls, a prominent Brooklyn preacher condemned light summer reading as “literary poison in August.” The social whirl of the summer resort didn’t lend itself to the solitary act of reading either. In 1877, in fact, Publishers’ Weekly, the industry’s major trade publication, warned book sellers that summer was “usually a dull time” and that they needed to do more to “push” light reading.

And push they did. To compete with the period’s pirate publishers who flooded the market with cheap paperback fiction, long-established publishers brought out their own paperback series with names that capitalized on the summer season. Appleton had its Town and Country Library, Cassell’s its Sunshine Series, and Houghton Mifflin its Camping Out Books. There was a Satchel Series, a Saunterer’s Series, and in the case of one newspaper, a 100-Degrees in the Shade Summer Fiction series.

Continuing with the marketing efforts that would reshape the literary marketplace, publishers put the label “summer reading” on advertisements for whatever books they had on hand — a backlist title, a steady-seller, a novel by a popular author. And in copy they most likely provided to news outlets themselves, they promoted specific titles as best picks for “idle summer days” or perfect for “the mountains or the seashore” or the talk of the summer resort.

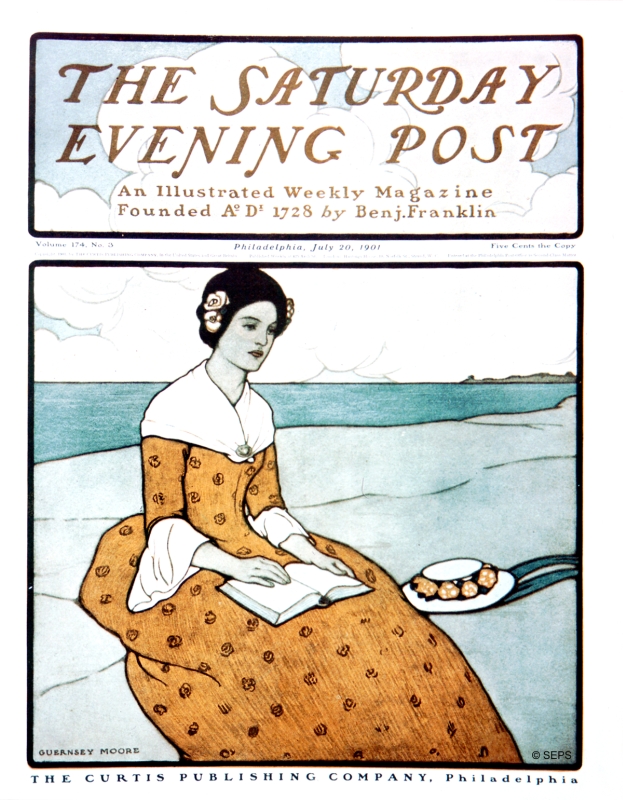

In the pages of the period’s taste-making monthly magazines — Harper’s, The Atlantic Monthly, The Century — summer novels became ways to fill up the vacant hours at a resort or protect against the boredom of rainy days. Not demanding too much attention, they were excellent company on long rides in Pullman cars. Episodic in structure, the best summer novels could be picked up and put down without losing the thread as other activities at resorts beckoned. And if these books were in paperback, all the better, noted The American Bookmaker. After all, paperbacks “have a cool and summery look, and from their flexibility may be readily stowed away in one’s pocket or thrust into an unfilled corner of a travelling bag.” They also adapted themselves “to every conceivable reading attitude, from bolt upright to the recumbent position assumed on a sofa or lounge, or in a steamer-chair, hammock or bed, or stretched out on a greensward or sandy beach.”

In short, taking aim at a criticism that equated novel reading with the sensational and the sinful, publishers worked to reframe — and repackage — “light summer reading” as a genteel act, a welcome escape from the pressures of 19th-century life, and an essential middle class pleasure.

The American Summer Novel

The book industry even introduced a new genre: the novel set specifically at a popular summer resort. Providing destination reading for readers at such resorts and vicarious pleasures for those who stayed home, these novels had plots built around resort activities — buckboard rides and picnics at Bar Harbor, going to the races at Saratoga Springs, taking part in a coaching parade in the White Mountains — letting them double as vacation guidebooks. Perhaps most important, with young women as their protagonists, the plots of many of these novels ended with marriage proposals and the promise of a wedding.

|

|

| Cover of One Summer written by Blanche Willis Howard and illustrated by Augustus Hoppin, published by James R. Osgood and Company in 1878 | Flirtations of a Beauty by Laura Jean Libbey, published by Norman L. Munro in 1890 |

Curiously, too, the genre attracted the attention of some of the most popular authors of the day. Laura Jean Libbey, the prolific and wildly successful author of paperback working-girl novels, used summer life in Newport, Lenox, and Long Branch as the settings for three of her novels. William Dean Howells, one of the period’s most prominent and prolific authors, used resort settings in more than a dozen of his novels. After the international success of The Red Badge of Courage, Stephen Crane tried his hand at a novel with a summer setting in The Third Violet. Mary Virginia Terhune, one of Scribner’s most popular authors who wrote under the pen name of Marion Harland, offered the publishing house her own take on the summer novel, this one set at a grand resort hotel on Mackinac Island, which Terhune had recently visited. The book ought to have “a fair summer sale,” Terhune told Scribner’s, and she could produce it quickly.

Those fair summer sales continue today. The summer reads of 2019 may come with hashtags (#TonightShowSummerReads) and audiences who vote online. Their covers may appear on Instagram and recommendations may be found increasingly on book blogs and podcasts. But their roots remain in the 19th century.

This article is based on the author’s book, Books for Idle Hours: Nineteenth-Century Publishing and the Rise of Summer Reading (2019) from the University of Massachusetts Press.

Featured image: Idle Hours by William Merritt Chase, circa 1894 (Wikimedia Commons, Amon Carter Museum of American Art)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now