Even the White House ushers were abuzz on the morning of October 10, 1963, because President John F. Kennedy was honoring the Mercury Seven — astronauts Lt. Scott Carpenter (USN), Capt. Leroy “Gordo” Cooper (USAF), Lt. Col. John Glenn (USMC), Capt. Virgil “Gus” Grissom (USAF), Lt. Cmdr. Walter “Wally” Schirra (USN), Lt. Alan Shepard (USN), and Capt. Donald “Deke” Slayton (USAF) — with the coveted Collier Trophy that afternoon in a Rose Garden affair.

The trophy had been established in 1911 to be presented annually for “the greatest achievement in aeronautics in America,” with a bent toward military aviation. At the Mercury ceremony were representatives from such Project Mercury aerospace contractors as McDonnell Aircraft Corporation (designers of the capsule) and Chrysler Corporation (which fabricated the Redstone rockets for the U.S. Army’s missile team in Huntsville, Alabama). Kennedy wanted to personally congratulate the “Magnificent Seven” astronauts, all household names, for their intrepid service to the country. And his remarks marked the end of the Mercury projects after six successful space missions.

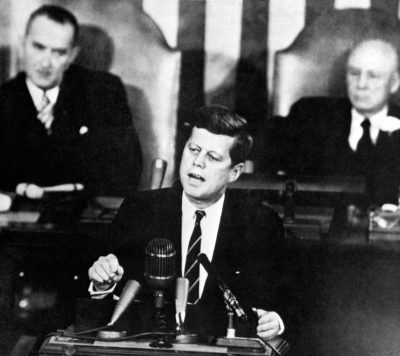

At the formal ceremony, Kennedy, in a fun-loving, jaunty mood, full of gregariousness and humor, presented the flyboy legends with the prize. Kennedy used the opportunity to drive home his brazen pledge of 1961, that the United States would place an astronaut on the moon by the decade’s end. Scoffing at critics of Project Apollo (NASA’s moonshot program) as being as thickheaded as those fools who laughed at the Wright brothers in 1903 before the Kitty Hawk flights, he turned visionary. “Some of us may dimly perceive where we are going and may not feel this is of the greatest prestige to us,” Kennedy said. “I am confident that its significance, its uses and benefits will become as obvious as the Sputnik satellite is to us, as the airplane is to us. I hope this award, which in effect closes out the particular phase of the program, will be a stimulus to them and to the other astronauts who will carry our flag to the moon and, perhaps someday, beyond.”

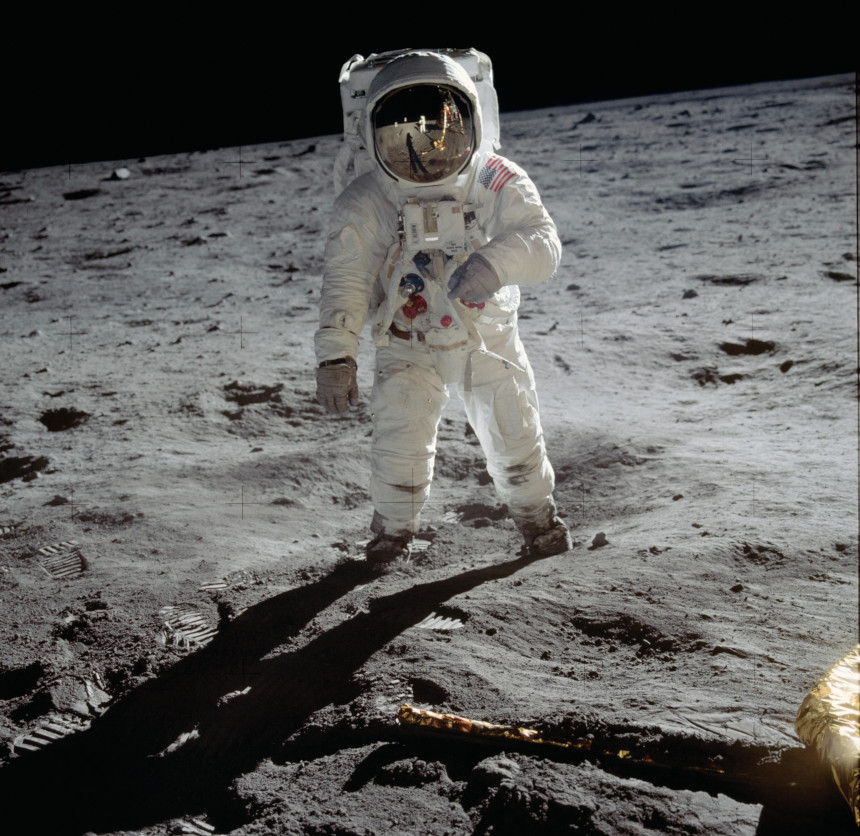

Even though Kennedy wasn’t alive for the fulfillment of his May 25, 1961, pledge to a joint session of Congress to land a “man on the moon” and return him safely to Earth, the marvel of television made it possible for more than a half-billion people to watch the historic Apollo 11 mission in real time, and I was one of them. On July 20, 1969, when Neil Armstrong gingerly descended from the spider-like lunar module the Eagle with his hefty backpack and bulky space suit, becoming the first human on the moon, I cheered like a banshee.

For years I longed to hear Neil Armstrong describe what it was like to contemplate Earth from 238,900 miles away, to explain, in his own words, the thermodynamics affecting motion through the atmosphere both in launching and reentry. Former Johnson Space Center director George Abbey of Houston (now a colleague of mine at Rice University) once told me that many NASA astronauts felt that looking at Earth was akin to a religious experience. Did Armstrong agree? What did it feel like, emotionally, spiritually, to stand on the surface of the moon? Armstrong’s reticence was legendary. He was known to be media shy.

It wasn’t until eight years later that NASA afforded me the privilege of interviewing Neil Armstrong for its official Oral History Project. I was surprised at and honored by the chance to speak in depth with the “First Man” — and thrilled when the date was set for September 19, 2001, in Clear Lake City, Texas. Then, eight days in advance of the big meeting, I saw the horrifying collapse of the World Trade Center towers on TV and listened to accounts of the two other disastrous airplane hijackings. A pervasive sense of gloom and urgency enveloped America. Like everyone else, I felt shock and repugnance at the ghastly scenes of our nation under attack, feelings that still burn to this day.

I was sure my Armstrong interview would be canceled. But it didn’t play out that way. To my utter astonishment, a NASA director telephoned me to say that Armstrong, no matter what, never missed a scheduled appointment. His effort to keep his word was legendary. The post-9/11 skies were largely shut to commercial aircraft, but Armstrong, whose own boyhood hero was flier Charles Lindbergh, refused to cancel his appointment at the Johnson Space Center, piloting his own plane from his adopted hometown of Cincinnati. It was a matter of honor, part of Armstrong’s “onward code.”

“I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth.”

—John F. Kennedy, 1961

The six-hour interview went well. When I asked Armstrong why the American people seemed to be less NASA crazed in the 21st century than back during John F. Kennedy’s White House years, he had a thoughtful response. “Oh, I think it’s predominantly the responsibility of the human character,” he said. “We don’t have a very long attention span, and needs and pressures vary from day to day, and we have a difficult time remembering a few months ago, or we have a difficult time looking very far into the future. We’re very ‘now’ oriented. I’m not surprised by that. I think we’ll always be in space, but it will take us longer to do the new things than the advocates would like, and in some cases, it will take external factors or forces which we can’t control.”

Moments later, I again tried to get Armstrong to loosen up and be more expressive about his lunar accomplishment, to defuse his engineer’s penchant for personal detachment. I had long pictured him in the sultry evenings at Cape Canaveral leading up to the Apollo 11 launch, looking up at the luminous moon and knowing that he and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin would soon be the first humans to visit a place beyond Earth. “As the clock was ticking for takeoff, would you every night or most nights, just go out and quietly look at the moon? I mean, did it become something like ‘My goodness?!’” I asked. “No,” he replied. “I never did that.” That was the extent of his romantic notions about the lifeless moon. Neil Armstrong was first and foremost a Navy aviator and aerospace engineer, following military orders with his personal best.

What became clear to me after interviewing him (and other Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo astronauts of 1960s fame) was that the story of the American lunar landing wasn’t wrapped up in any idealized aspiration to walk on the moon surface; instead, it was all about the old-fashioned patriotic determination to fulfill the pledge made by President Kennedy on the afternoon of May 25, 1961. “I believe,” our 35th president had said before Congress, “that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before the decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth.”

Only one top-tier Cold War politician had the audacity to risk America’s budget and international prestige on such a wild-eyed feat within such a short time frame: In John F. Kennedy, the man and the hour had met. Without Kennedy’s daunting vow to send astronauts to the moon and bring them back alive in the 1960s, Apollo 11 would never have happened in my childhood. It’s my contention that if JFK had been wired differently — if he hadn’t had such a hard-driving father who raised him with the need to achieve great things, or a brother who died in World War II trying to destroy a German missile facility — then the moonshot might not have happened.

For Kennedy, who himself became a World War II naval hero for his bravery in the PT-109 incident of 1943 in the Pacific Theater, the Project Mercury astronauts were ultimately fearless public servants like him. The NASA astronauts Kennedy had feted in the Collier Trophy ceremony weeks before his assassination volunteered for space travel duty at a pivotal moment in the Cold War. Like Kennedy, these astronauts were courageous, pragmatic, and cool; they were husbands and fathers who, as journalist James Reston noted, “talked of the heavens the way old explorers talked of the unknown sea.” Kennedy’s New Frontier ethos was based on adventure, curiosity, big technology, cutting-edge science, global prestige, American exceptionalism, and historian Frederick Jackson Turner’s famous “frontier thesis.” All six of NASA’s Mercury missions occurred during Kennedy’s presidency. With Madison Avenue instinct, Kennedy routinely claimed that space was the “New Ocean” or “New Sea.” If so, then he was the navigator in chief ordering NASA spacecraft with noble names such as Freedom, Liberty Bell, Friendship, Aurora, Sigma, and Faith into the great star-filled unknown. His talent for converting Cold War frustration over Soviet rocketry success into a no-holds-barred competition for the moon was politically masterful. And the American public loved him for leading the effort.

It’s fair to argue that NASA’s Projects Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo were just a shiny distraction, that the taxpayers’ revenue should’ve been spent fighting poverty and improving public education. But it’s disingenuous to argue that Kennedy’s moonshot was a waste of money. The technology that America reaped from the federal investment in space hardware (satellite reconnaissance, biomedical equipment, lightweight materials, water-purification systems, improved computing systems, and a global search-and-rescue system) has earned its worth multiple times over. Ever since, whenever we have worried about an America in decline, Kennedy’s moonshot challenge has stood as the green light reminding us that together as a society we can accomplish virtually any feat.

Full of blithe optimism, Kennedy’s pledge set an audacious goal, capping a three-and-a-half-year period in which the Soviet Union twice shocked the world, first by launching the first orbital satellite, on October 4, 1957, and then by sending cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin on the first manned space mission on April 12, 1961, just six weeks before Kennedy’s rally cry to Congress. For a world locked in a Cold War rivalry between the Americans and the Soviets, space quickly became the new arena of battle. “Both the Soviet Union and the United States believed that technological leadership was the key to demonstrating ideological superiority,” Neil Armstrong explained later. “Each invested enormous resources in ever more spectacular space achievements. Each would enjoy memorable successes. Each would suffer tragic failures. It was a competition unmatched outside the state of war.” Kennedy, with depth and commitment, articulated a visionary strategy to leapfrog America’s communist rival and win that high-stakes contest in the name of the capitalistic free-market system as represented by the United States. It was just a matter of figuring out how to do it, using engineering exactitude, military know-how, taxpayer dollars, and political pragmatism.

Calculating that the American spirit needed a boost after Sputnik, Kennedy decided that beating the Soviets to the moon was the best way to invigorate the nation and notch a win in the Cold War. But he also understood that a vibrant NASA manned space program would involve nearly every field of scientific research and technological innovation. U.S. leadership in space required specialists who could innovate tiny transistors, devise resilient materials, produce antennae that would transmit and receive over vast distances never before imagined, decipher data about Earth’s magnetic field, and analyze the extent of ionization in the upper atmosphere. President Kennedy bet that a lavish financial investment in space, funded by American taxpayers, would pay off by uniting government, industry, and academia in a grand project to accelerate the pace of technological innovation. He doubled down on Apollo even while calling for tax cuts. Breaking up congressional logjams over NASA appropriations became a regular feature of his presidency.

Though the cost of Project Apollo eventually exceeded $25 billion, the intense federal concentration on space exploration also teed up the technology-based economy the United States enjoys today, spurring the development of next-generation computer innovations, virtual reality technology, advanced satellite television, game-changing industrial and medical imaging, kidney dialysis, enhanced meteorological forecasting apparatuses, cordless power tools, bar coding, and other modern marvels. Shortsighted politicians may have carped about the cost, but in the immediate term, NASA funds went right back into the economy: to manned space research hubs such as Houston, Cambridge, Huntsville, Cape Canaveral, Pasadena, St. Louis, the Mississippi-Louisiana border, and Hampton, Virginia, to the thousands of companies and more than 400,000 citizens who contributed to the Apollo effort.

“We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.”

—John F. Kennedy, 1962.

Even without the manifest technological and societal benefits of Apollo, Kennedy would have set a course to the moon because he believed America had an obligation to lead the world in public discovery. For though the moon seemed distant, in reality, it was only three days away from Earth. On September 12, 1962, at the Rice University football stadium, Kennedy offered the nation a stirring rationale for Apollo. Identifying the moon as the ultimate Cold War trophy and throwing his weight behind landing there was the most daring thing Kennedy ever did in politics. “Why, some say, the moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask, why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic? … We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win.”

During Kennedy’s Rice speech, he deemed space the ocean ready to be explored by modern galactic navigators. “We set sail on this new sea,” he said, “because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all people.” By the time Kennedy stepped down from the Rice dais, his memorable words had been seared into the imaginations of every rocket engineer, technician, data analyst, and astronaut at NASA. It was that rare moment when a president outperformed expectations. “The eyes of the world now look into space,” he had vowed, “to the moon and to the planets beyond, and we have vowed that we shall not see it governed by a hostile flag of conquest, but by a banner of freedom and peace. We have vowed that we shall not see space filled with weapons of mass destruction, but with instruments of knowledge and understanding. Yet the vows of this nation can only be fulfilled if we in this nation are first, and, therefore, we intend to be first. In short, our leadership in science and in industry, our hopes for peace and security, our obligations to ourselves as well as others, all require us to make this effort, to solve these mysteries, to solve them for the good of all men, and to become the world’s leading space-faring nation.”

Throughout the United States there is a hunger today for another “moonshot,” some shared national endeavor that will transcend partisan politics. If Kennedy put men on the moon, why can’t we eradicate cancer, or feed the hungry, or wipe out poverty, or halt climate change? The answer is that it takes a rare combination of leadership, luck, timing, and public will to pull off something as sensational as Kennedy’s Apollo moonshot. Today there is no rousing historical context akin to the Cold War to light a fire on a bipartisan public works endeavor. Only if a future U.S. president, working closely with Congress, is able to marshal the federal government, private sector, scientific community, and academia to work in unison on a grand effort can it be done. NASA has achieved other astounding successes in the realm of space, such as exploring the solar system and cosmos with robotic craft and establishing a space station, but without presidential drive, these didn’t galvanize the national spirit. Kennedy’s moonshot was less about American exceptionalism, in the end, than about the forward march of human progress. For as the Apollo 11 plaque left on the moon by Armstrong and Aldrin reads, WE CAME IN PEACE FOR ALL MANKIND.

This article is featured in the July/August 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: NASA

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Excellent article Mr. Brinkley. There’s so much you’ve said here I could reply to, that it would be too long. First of all, congratulations on being able to interview Neil Armstrong just 8 days after the 9/11 tragedy. That had to have been very difficult, yet you and he didn’t let that horrific tragedy deter you.

When all is said and done, President Kennedy himself was ‘ground zero’ for what culminated in the successful 1969 Apollo 11 Moon Landing for all the reasons you mention, both political and personal. I don’t think he was ever very far away away from most Americans thoughts after his assassination, knew how important this was to him, and also wished to see it fulfilled. (NASA goes without saying.)

Although his life and Presidency were cut short, this was one HUGE accomplishment that the Kennedy Administration made and deserves the credit for, even though it didn’t actually occur until Nixon’s.