Author of the novels The Cool World and Flush Times, Warren Miller gained recognition for his political fiction in the 1950s and ’60s that depicted inner city racial tensions. His short story “Chaos, Disorder, and The Late Show,” is a slice of life for a quirky accountant and his aging parents. The story was included in an O. Henry Prize Stories collection.

Published on October 2, 1963

I am a certified public accountant and a rational man. More exactly, and putting things in their proper order, I am a rational man first and an accountant second. I insist on order; I like the symbols of order — a blunt, hardy plus sign or a forthright minus delights me. I make lists, I am always punctual, I wear a hat. Maltz believes this has caused my hairline to recede. Maltz is one of my associates at the office. He married too young and he regrets it.

In fact, there is no scientific foundation for his view that wearing a hat causes the hairline to recede. Such things are largely a matter of heredity, although my father has a luxuriant head of hair. But what of my grandfathers? I have no doubt that one of them accounts for my high forehead. Talent, I believe I have read somewhere, often skips a generation or jumps from uncle to nephew. Studies have been made. Naturally there are exceptions. But it provides one with the beginning of an explanation. The notion of having been an adopted child is a fancy I have never indulged. I have never doubted that my parents are my true parents. But I sometimes suspect they think I am not their true son.

Let me say just this about my father: He is a high-school history teacher, and every summer for twenty-five years he has had a three-month vacation. Not once has he ever put this time to any real use. He could have been a counselor at a camp, taught the summer session, clerked at a department store or … any number of things. I recall that he spent one entire summer lying on the sofa, reading. Some years he goes to the beach. Once he went to Mexico. His income is, to be sure, adequate, but I am certain that one major illness would wipe out his savings. I have tried to speak to him about preplanning; he listens, but he does not seem to hear.

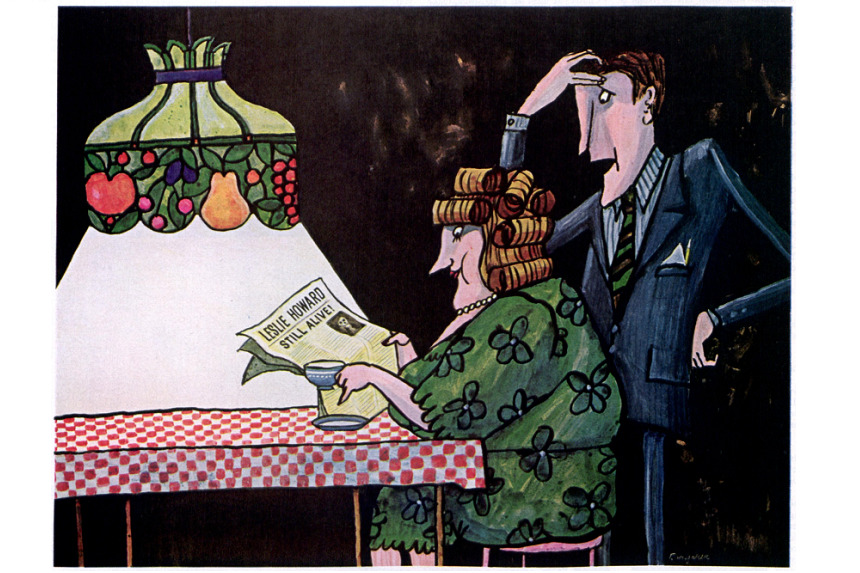

My mother — I think this one example will suffice — my mother believes that Leslie Howard, who was a Hollywood actor killed in the war, is still alive. My father merely smiles when she speaks of Leslie Howard — I believe he actually enjoys it — but I have brought home almanacs and circled references in Harper’s and other magazines attesting to the fact that Leslie Howard is, in fact and in truth, dead. Definitive proof.

Not that I care; not that I care very deeply. It is a harmless-enough delusion; but it is sloppy. I believe that the world tends naturally to chaos and that we all have to make our daily — even hourly — contribution toward order. My parents, in my opinion, are unwilling to shoulder their share of this responsibility.

I have, once or twice, discussed the matter with Maltz, whose wife has proved to be unreliable in some ways and who has a sympathy in matters of this kind. Maltz agrees that my father is mistaken in his indulgent attitude; on the other hand, he believes it would, perhaps, be better psychologically if I ignored my mother’s pitiful little delusion — as he called it.

But it is like a pebble in my shoe or loose hair under my shirt collar. Chaos and disorder in the world, in the natural scheme of things, is bad enough; one does not want to have to put up with it at home too. The subways are dirty and unreliable; the crosstown buses are not properly spaced; clerks in stores never know where their stock is.

The extent of the breakdown is incredible. Every year at this time I rent an empty store on upper Broadway and help people with their income-tax returns. These people keep no records! They have no receipts! They lose their canceled checks! They guess! The year just past is, to them, a fast-fading and already incomplete collection of snapshots. It was full of medical and business expenses and deductions for entertaining, yet they remember nothing. Believe me, the chaos of subways and crosstown buses and our traffic problems is as nothing compared to the disorder in the heads of people . Every year I am struck with this anew.

This extra-time work continues for three months and becomes more intense as deadline time draws near. It is amazing how many people wait until the last possible moment. Often I am there until nearly midnight.

At the beginning of March, I hire Maltz and pay him by the head. He is not as fast as I would like, but he is reliable and, because of his wife and her extravagances, he needs the money. “It would embarrass me,” he says, “if I had to tell you how much she spends every week on magazines alone.”

Poor guy.

I live with my parents. The store I rent is near their apartment, a matter of three blocks, walking distance. It is a neighborhood of small shops and large supermarkets which once were movie houses; their marquees now advertise turkeys and hams. Maltz occasionally will walk me to my door.

That night, the night of the incident, it was snowing. It had been snowing all day. No one had cleaned his sidewalk, and it made walking treacherous. I almost slipped twice.

“Isn’t there a city ordinance about people cleaning their sidewalks? Isn’t it mandatory?” I asked.

Maltz said, “There is such an ordinance, Norman, but it is more honored in the breach than in the practice.”

The sadness of his marriage has given Maltz a kind of wisdom. The next time he slipped I took his arm, and I thought, Here is a man who might one day be my friend. The loneliness of the mismated is a terrible thing to see. It touches me. I believe I understand it. At the door of my building I said good night and I watched for a moment as Maltz proceeded reluctantly toward home.

The elevator was out of order again. When a breakdown occurs, tenants must use the freight elevator at the rear of the lobby. I had to ring for it three times and wait more than five minutes; then I had to ride up with two open garbage cans. It was not very pleasant. The elevator man said. “How’s business, Mr. Whitehead?”

“Very good, thank you, Oscar,” I said.

“I’ll be in to see you real soon, Mr. Whitehead.”

I nodded. I knew he’d wait, as he did last year, until the last possible moment. I tried to shrug it off. It’s no good trying to carry the next man’s share on your own shoulders, I told myself. Forget it, I thought.

Because I had come up in the freight elevator, I therefore entered our apartment by way of the kitchen. I took off my rubbers and carried them in with me, my briefcase in the other hand. As a result, the door slammed shut, since I had no free hand to close it slowly.

“Is it you?” my mother called.

She was at the kitchen table having her midnight cup of tea; she said it calmed her and made sleeping easier to have tea before bed. I have tried to explain to her that tea has a higher percentage of caffeine than coffee, but she continues to drink it.

She was smiling.

“What is it?” I said.

“Mr. Know-it-all, come here and I would like to show you something.”

She had a newspaper on the table. I did not move. “What is it?” I asked.

“Come here and I will show you, Norman,” she said, still smiling.

At this point my father shouted something unintelligible from their bedroom.

“What did you say, dear? What?”

“Bette Davis on the late show. Dark Victory !”

My mother put her hand to her heart. “I remember the day I saw it,” she said. “At the Rivoli, with Millie Brandon.” She sat there, staring at nothing; she had forgotten all about me.

“What was it you wanted, Mother?” I said.

“Twenty-five cents if you got there before noon, would you believe it,” she said.

I looked at the newspaper. I was astonished to see that she had brought such a newspaper into the house. There it was, beside her teacup, one of those weekly papers that always has headlines such as: MOTHER POISONS HER FIVE BABIES or TAB HUNTER SAYS “I AM LONELY.” The inside pages, I have been told, are devoted to racing news.

“Mr. Know-it-all,” she said and began to smile again.

“What are you doing with that paper, Mother?”

“Millie called me this afternoon and I ran out and bought it. Look!” she cried, and with an all-too-typical dramatic flourish she unfolded it and showed me the front page. The headline read: LESLIE HOWARD STILL ALIVE.

“So much for your almanacs and your definitive proof,” she said. “Now what have you got to say, my dear?”

“Two minutes, dear,” my father called in to her. “Commercial on now.”

“Coming,” she called back.

“Mother,” I said, “you know very well what kind of paper this is.”

“Why should they pick this subject?” she said, tapping the headline with her fingernail. “Why should they pick this particular subject right out of the blue? I would like to ask you that.”

“Did you read the article itself, Mother? Is there one iota of hard fact in it?”

“There are facts, and there are facts, my dear boy.”

I was very patient with her. “Mother,” I said, “he is dead. It is well known that he is dead. He went down at sea in a transport plane … ”

“First of all, Mr. Smart One, it was not a transport. It was a Spitfire. He always flew Spitfires. He and David Niven.”

“Well, then, Mother, just tell me this,” I said. “If he’s alive, where is he? Where is he?”

“It’s starting, dear,” my father called.

“The loveliest man who ever walked this earth,” she said.

“I have never had the pleasure of seeing him, Mother.”

“Steel-rimmed glasses. A pipe. Tweed jackets.”

“Well, where is he, Mother?”

“So gentle. Gentle, yet dashing. If everybody was like Leslie Howard, wouldn’t this be one beautiful world. Oh, what a beautiful world it would be!”

“Under no circumstances would I trust that particular newspaper,” I said.

“This newspaper, my dear boy, is like every other newspaper. It is sometimes right.”

I put my rubbers under the sink.

“The year you were born I saw him in Intermezzo , Ingrid Bergman’s first American movie. Produced by Selznick, who was then still married, I believe, to Louis B. Mayer’s daughter Irene.” She sipped her tea and looked at the headline. She said, “These days they don’t even name boys Leslie anymore. Girls are now named Leslie. Before the war people had such lovely names. Leslie, Cary, Myrna, Fay, Claudette. What has happened?”

She looked at me as if it were all my fault. “I don’t know what’s happened, Mother,” I said, perhaps a little testily.

“It’s your world, my dear; therefore you should know,” she said. “Nowadays they even name them after the days of the week.”

“I have named no one after any day of the week, Mother,” I said, but she was not listening.

“You could always find a parking place. People were polite. Self-service was unheard of. Frozen food was something to be avoided at all costs.”

“I can put no confidence at all in that particular newspaper,” I said. “Absolutely none.”

“Then I am sorry for you and I pity you,” she said in a manner that I thought entirely uncalled for.

“Why? Why should you be sorry for me and pity me?” I asked.

I waited for her to answer, but she went back to sipping her tea and reading the headline.

“I have a good job,” I said, “and I am doing the work I like.”

“Nevertheless, Norman, I feel sorry for you.”

I had not even taken off my overcoat, and 1 was forced to put up with an attack of this nature! I was struck by the unfairness of it. I said, “You know what a silly newspaper that is, Mother. What is the matter with you? You know he is dead. I know you know it. Everybody knows that he is dead.”

She banged down her cup. “He is not!” she said. “He is not dead! He is not!”

“What’s going on in there?” my father called.

“He is alive!”

“Then where is he?” I demanded, and I raised my voice, too; I admit that I raised my voice. “Where is he?”

“Oh,” she said as if she were completely disgusted with me. “Oh, Mr. Born Too Late, I’ll tell you where he is,” she said, getting up from her chair, the newspaper in her hand. And she began to hit me on the head with it. She hit me on the head with it. Every time she mentioned a name she hit me. “I’ll tell you where he is, I’ll tell you where he is. He is with Carole Lombard and Glenn Miller and Will Rogers and Franklin …”

I ran out of the room. Why argue? She has a harmless delusion. From now on I will try to ignore her when she gets on this particular subject. Maltz may be right about this. I hung up my coat. Fortunately it is only when I stand at my closet door that I can hear the sound of their television set, which often goes on until three in the morning. Once I shut that door, however, my room is perfectly silent.

Illustration by Tomi Ungerer (SEPS)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This is a really well written story. I love the fact it’s mainly conversational and is still entertaining over 55 years later. Can’t you just picture it being acted out on the stage?

When I first saw the title of the story, I thought of ‘The Late Show’ with David Letterman since he left as host. And the unwatchable ‘romper room zoo’ mess ‘The Tonight Show’ has been since Jay Leno left as host. The one on ABC isn’t worth mentioning in the first place, past or present.