It’s February 20, 1862. The nation is torn by Civil War. Elements of the Union Army camp along the Potomac River; men and horses alike are struggling with the bitter cold. Yards away, inside the home of the president, a different struggle draws to an end. There’s a killer in the White House, and before the night is over, what that killer does will irrevocably shatter the Lincoln family.

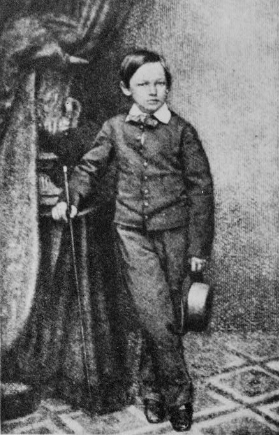

Young Willie Lincoln is his father’s favorite, if he would admit such a thing. He’s also his mother’s favorite. His older brother Robert is away at Harvard, and his younger brother Eddie died at age three. Eight-year-old Tad Lincoln is the “notorious” hellion; the White House is his jungle gym and he’s known for an unrestrained free spirit. But Willie, Willie is like his father. Even at 11, he takes the role of the serious older brother; family friends describe him as bright and lovable. Willie loves to read and write. He’s one of the bright points for his father in a dark time in history. But on the evening of February 20, Willie Lincoln lies in a bed on the second floor of the White House, with his mother and father at his side, gasping for air and clinging to life. It would be on this evening, in this room, where Willie Lincoln succumbed to a silent killer.

Initially, Mary Lincoln blamed his death, and that of Eddie, on the family’s political ambitions. In a letter to a friend she wrote, “Our heavenly Father seems fit to visit us at such times, for our worldliness.” What Mary Lincoln did not know is that Willie’s death was not the poisoned fruit of political ambition, but more likely, it was caused by the same disease that stole the life of three former presidents and countless other Washington, D.C. residents in years past.

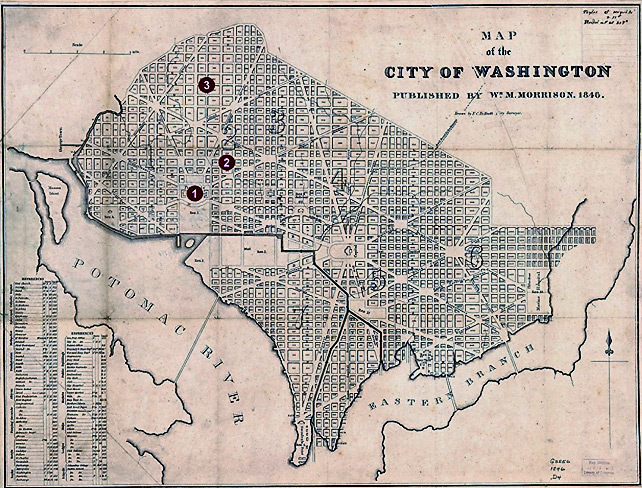

To understand what may have claimed the lives of these victims we have to take a look at Washington, D.C. at the turn of the 19th century. The new federal city was supposed to be a shining beacon of democracy and freedom; instead, it was an overgrown swamp with primitive roads and almost no infrastructure. John Adams became the first president to move into the White House in November of 1800. The would-be mansion was damp, poorly ventilated, and a far cry from what tourists see today on Pennsylvania Avenue. Abigail Adams famously lamented about having to hang the family laundry to dry in the East Room.

The rest of Washington, D.C. was not much better off. The small, makeshift city was struggling with some of the more basic municipal maintenance concepts that Americans take for granted today. One of those non-existent amenities was solid waste processing. The lack of a sewer system caused early residents to leave their so-called “night soil” in the streets. It would then be collected and deposited in a sparsely populated section of the near north side of the city.

This night soil depository was believed to be in the vicinity of the modern intersection of 15th Street and R Street. Today, the quiet residential neighborhood is home to a hostel and a Presbyterian church. And while its residents today may not know, the effects of what happened in this neighborhood may have had long lasting consequences on the history of the United States.

In the early years, water was carried in buckets to the White House by servants and stored in two wells inside breezeways. Piping running water into the White House was first proposed during the James Madison administration, but before this work could be started, the White House was burned to ashes by the British in 1814 during the War of 1812. In 1829, the Committee on Public Buildings again proposed piping water into the White House. The purpose was not for bathrooms, toilets, or kitchen use, but instead for fire protection. With the 1814 torching still fresh in their memory, officials were nervous about the possibility of another fire destroying the president’s house. Up to this point, the only fire protection the White House had was a fire engine that was purchased by President James Monroe and was parked in the carriage house behind the White House. Ultimately, instead of appropriating the funds to install the pipes for running water, the committee spent the money on repairing the north portico of the White House.

Besides gaining funding for the project, another issue was the question of how to get the water to the White House. With the lack of ground water beneath the house, the Committee on Public Buildings set out to find a suitable source of water nearby. In a letter to President Thomas Jefferson on May 27, 1807, surveyor Nicholas King proposed pumping water from a spring just six blocks north of the White House. Located at the intersection of Massachusetts Avenue and 16th Street West (the current location of the General Winfield Scott statue), the spring sat at an elevation of about nine feet above the White House. King suggested delivering the water to the White House from the spring using a series of pipes.

But this proposed site and plan was never used. Instead, the Committee on Public Buildings purchased a spring in Franklin Square in 1831. The site was only four blocks northeast of the White House and was closer than the site that King suggested in 1807. Ground was broken on the site in 1833. Engineer Robert Leckie was put in charge of the project. Leckie had extensive experience in leveling streets and building water lines in Georgetown and Washington, D.C.

Leckie used iron pipes to run the water from the spring in Franklin Square to three small reservoirs located in the Treasury building, the State Department, and the White House. Since the spring was at a higher elevation than the White House, gravity did most of the work. Leckie completed this system at the end of May, 1833.

President Andrew Jackson was the first resident in the White House to take advantage of this new running water. No concern was given to the pipes, the water, its source, or even the bacteria-filled night soil depository that was located uphill, less than a mile away from the spring.

Complicating matters in Washington, D.C. was the city canal. As if the contaminated water from the Franklin Square spring weren’t enough of a health risk, the Washington, D.C. canal was a danger all on its own.

The canal ran along what is now Constitution Avenue in Washington, D.C. It was an original feature of the city, designed to connect the Anacostia River with Tiber Creek. Since the canal ran through the heart of Washington, D.C. and bordered the National Mall, it was subject to a lot of misuse. Soon after its opening in 1815, it quickly became nothing more than an open sewer, with reports of citizens dumping raw waste and animal carcasses. Since it was not covered, many drunken patrons, fresh from a visit to the local pub, found themselves immersed in its filthy waters. A foul stench emanated from it, exacerbated by the long and hot Washington, D.C. summers.

The canal ran only one block south of the White House. It is easy to see how bacteria and disease could find its way onto the White House grounds from such a lengthy, uncovered channel.

The threat from the canal was compounded by the Potomac River. Visitors to Washington, D.C. today would have to walk over two miles from the White House to reach the banks of the river, but up until the late 19th century, the Potomac River stretched across the National Mall and reached the city canal. It was not until the completion of the Washington Monument that officials began to dredge the land around the mall and fill it in with earth, pushing the river back to its present-day boundaries. The city canal was finally covered in 1872. The local drunks could now freely walk about without fear of falling to a slimy fate.

But recent research shows that all of these factors presented a larger danger than anyone at that time would realize.

In March of 1841, President William Henry Harrison delivered his infamous inaugural address, a two-hour speech made in cold and rainy conditions that many at the time believed caused his untimely death the following month. But over a century-and-a-half later, science points to a different source of the president’s demise.

In a 2014 study for Oxford Academic, Jane McHugh and Philip Mackowiak theorize that Harrison was actually killed by the running water in the White House. Their study first takes a look at the initial diagnosis from Harrison’s doctor, Thomas Miller; Miller claimed that the president’s eventual cause of death was pneumonia. However, the symptoms Harrison displayed during the time he lay on his deathbed in the White House were more consistent with that of enteric fever and a gastrointestinal infection, which could have been brought on by a parasite or bacteria introduced through contaminated water in the White House.

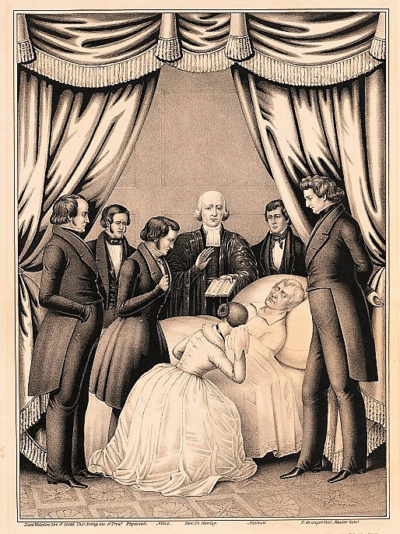

Harrison initially complained to Dr. Miller of anxiety and fatigue three weeks after his inauguration. These ailments quickly gave way to nausea, constipation, and a rising body temperature. These symptoms were treated with a steady regimen of mustard plasters, laxatives, laudanum, and enemas. Obviously, Dr. Miller was treating President Harrison’s symptoms, and not the actual cause of his ailments.

In their study, McHugh and Mackowiak theorize that since Harrison’s “pulmonary symptoms were not as severe as his gastrointestinal distress,” it is more likely “that he died of a gastrointestinal infection.” They go on to explore the possibilities of this infection being the product of the bacteria S. paratyphi. President Harrison’s infrequent, and then frequent (thanks to the many laxatives he was given) stool samples strongly resembled those of typhoid patients (in fact, a number of sources attribute Harrison’s death to typhoid, treating it as a settled question). The Oxford Academic study concludes, “There is ample reason to conclude that Harrison’s move into the White House placed him at particular risk of contracting enteric fever.”

Rather than the inclement weather, the water that Harrison drank, bathed in, and cleaned with was more than likely the cause of his demise.

As Harrison lay in his deathbed on the evening of April 3, 1841, he uttered his final words; “Sir, I wish you to understand the principles of government; I wish them carried out, I ask nothing more.” Over the next four hours, his pulse would slowly drop, until he stopped breathing at 12:30 the next morning.

Only eight years later, an eerily similar situation was playing out in Nashville, Tennessee. On June 15, 1849, James K. Polk lay in a bed, his body rocked by diarrhea, vomiting, and severe dehydration. Only three months prior, Polk was finishing up his only term as President of the United States. But now, he was consumed by cholera morbus; a common gastrointestinal illness.

Polk spent most of his life fighting various illnesses. From kidney stones to gallstone removal, he was no stranger to fighting back from ill health. But this bout of cholera was too much for the 53-year-old.

While it’s not possible to definitively link the contaminated water in the White House to the death of a former occupant, the similarity in the symptoms between Polk and Harrison are striking. The gastrointestinal issues that haunted Harrison in his final days reappear in Polk, shortly after Polk left the White House. These symptoms are most commonly the result of the introduction of a waterborne bacterial parasite, like S. paratyphi. In the four years that separated the death of Harrison and the inauguration of Polk, little improvement was made on the White House water system.

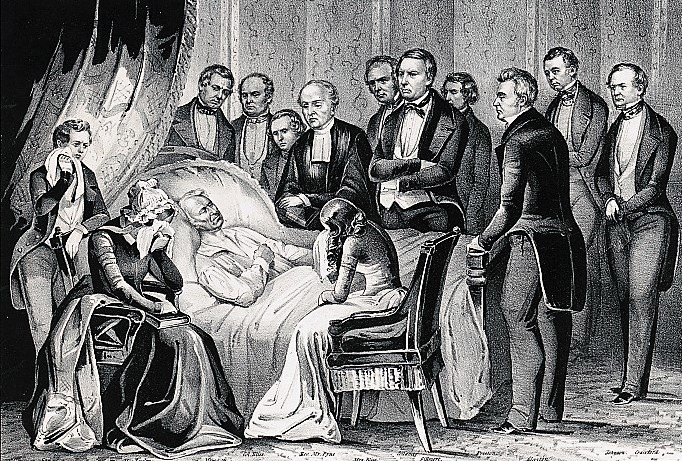

While Polk made it out of the White House before he succumbed, his immediate successor did not. Just a year-and-a-half after taking office, President Zachary Taylor found himself in an ominous position.

It was commonly accepted that President Taylor became ill after consuming too much iced milk and cherries on July 4, 1850. But in a 2003 biography of Taylor, The Life of Major General Zachary Taylor: Twelfth President of the United States, author Henry Montgomery reveals that Taylor also “partook freely of water” during his Independence Day binge eating session. Within an hour of eating the cherries and drinking large amounts of iced milk and water, Taylor began to complain of cramping. These cramps gave way to vomiting, diarrhea, and other symptoms that are associated with water-borne illnesses, including cholera and typhoid.

Five days later, after fits of violent diarrhea and vomiting, it was time for Taylor to take his place in history by uttering his last words: “I have endeavored to do my duty, I am prepared to die. My only regret is in leaving behind me the friends I love.” Had the water in the White House claimed its third president in six years?

Back at the White House, little progress was made on the sourcing and sanitization of running water. In 1860, President James Buchanan ordered running river water to be pumped to the second floor of the White House for bathing. Luckily for Buchanan, that work was not completed until his successor and his family moved into the White House.

Young Willie Lincoln was strong, exuberant, and full of life. Unfortunately, he, like three presidents before him, was likely not strong enough to overcome decades of mismanagement with the White House plumbing system. At the time he fell ill, water from the tainted spring in Franklin Square was still being used in the White House. The open and festering city canal was still running just one block south of his home. Willie and his younger brother would often climb to the roof of the White House and look out on Union soldiers who were camped along the Potomac River, just a few blocks away. Little did Willie know that those soldiers were often relieving themselves and dumping discarded animal carcasses in that river. That very same water was being piped upstairs to the second floor of the White House, and young Willie was likely bathing in it frequently. He was unaware of the microscopic bacteria that was entering his body. As with the deaths of Presidents William Henry Harrison, James K. Polk, and Zachary Taylor, this was likely his silent killer.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

The Harrison line in question refers to his speech, which was given in March of 1841. Of course, 1841 is not 1844. We regret the error.

Just a quick note, William Henry Harrison was elected in 1840, not 1844.

Thank you for this informative article! I, too was not aware of how poor water quality was in Washington, DC. A big Thank you to the employees of water treatment plants who toil tirelessly behind the scenes in today’s America.

This is the first article I’ve ever read concerning this devastating ‘silent killer’ that came from the White House water system, killing three Presidents. Microscopic waterborne bacterial parasites are something they would have had had no idea was happening, obviously, if the water looked and tasted normal.

It’s a wonder more didn’t die at the White House and surrounding areas per this report. S. paratyphi, cholera and other diseases are still major problems to this day in India, Africa and other areas keeping Medecins san Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders) busy 24/7, 365 days per year healing and saving lives of so many thousands affected by such water contamination. Whatever you can afford to give goes directly toward the medical supplies and all that’s needed for their work.

They work tirelessly too of course, to see that the water, from its source, is free of disease and remains that way. It’s an organization well worth supporting, to help people in other nations end suffering that is not their fault, anymore than it was here in the 19th century, or in the centuries before or after.

It is sad and ironic that such water pollution was so close to the White House. It was a perfect storm of unfortunate circumstances per description coming together that caused so much illness, misery and death. When you see the President’s House as in 1860 here, you’d never think it wouldn’t have safe, modern plumbing. You would be wrong. Historically speaking, the water safety we take for granted today is still a relatively recent advancement.