This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

On February 14, Senator Kamala Harris introduced legislation into the Senate that would for the first time in American history make lynching a federal crime. The Justice for Victims of Lynching Act, originally drafted by Harris in June 2018, does more than just criminalize lynching—as its name suggests, it seeks to remember and in some small ways make amends for the thousands of lynchings that took place between the end of the Civil War and the 1960s. “With this bill,” Harris said, “we finally have a chance to speak the truth about our past and make clear that these hateful acts should never happen again. We can finally offer some long overdue justice and recognition to the victims of lynching and their families.”

The horrific stories of lynching are intimately intertwined with African American history, a significant factor in Harris’s choice to introduce the bill during Black History Month. Yet as with any American histories, lynching’s connections extend to every national community. For Women’s History Month, Harris’s prominent role in these unfolding 21st century accounts can also help us remember the fraught, contradictory, and crucial links between American women and the lynching epidemic.

Perhaps the single most jarring defense of lynching was offered by a pioneering feminist activist. Rebecca Ann Latimer Felton, the wife and political partner of longtime Georgia Congressman William Harrell Felton, was one of the Progressive Era’s most prominent and acclaimed women’s rights activists: an advocate of women’s suffrage, equal pay, and many other feminist causes, she became the first woman to serve in the U.S. Senate when, at the age of 87, she was honored with a single-day appointment as Senator from Georgia on November 21, 1922. Yet she was also a white supremacist and racist who openly advocated for the systematic lynching of African Americans.

Felton made her case for lynching most vocally in an August 1897 speech to the Georgia Agricultural Society. While she identified a number of problems facing (white) farm wives in the state, she focused in particular on “the black rapist” and the threat he posed to those women. She repeated the canard that Reconstruction had given African Americans “license to degrade and debauch.” And in response to those imagined terrors, she argued, “When there is not enough religion in the pulpit to organize a crusade against sin; nor justice in the court house to promptly punish crime; nor manhood enough in the nation to put a sheltering arm about innocence and virtue—if it needs lynching to protect woman’s dearest possession form the ravening human beasts—then I say lynch, a thousand times a week if necessary.”

Felton’s bigoted speech reminds us that the era’s progressive white women far too often allied with the forces of segregation and white supremacy, both to further their movement’s goals and (as in Felton’s case to be sure) out of genuine and deeply rooted racism. Yet as historian Martha Jones has recently argued, the under-appreciated contributions of African American women to the women’s suffrage movement played a crucial role in advancing women’s right to vote. One of the most prominent such African American suffrage activists, Ida B. Wells, also happened to be the nation’s leading anti-lynching journalist and crusader.

The opening pages of Wells’s first book, Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases (1892), reflect the intersections of her women’s rights and anti-lynching activism. In her preface, Wells acknowledges the fundraising efforts of New York City women’s rights organizations that allowed her to publish the book, writing, “the noble effort of the ladies of New York and Brooklyn Oct. 5 have enabled me to comply with this request and give the world a true, unvarnished account of the causes of lynch law in the South.” Wells highlights both her own status as a target of white supremacist violence (when her Memphis newspaper office was burned down) and her courageous response to those attacks: “Since my business has been destroyed and I am an exile from home because of that editorial, the issue has been forced, and as the writer of it I feel that the race and the public generally should have a statement of the facts as they exist.” As an African American woman speaking out against these horrors, she likewise revises Felton’s images of race and gender, noting, “[The facts] will serve at the same time as a defense for the Afro-Americans Sampsons who suffer themselves to be betrayed by white Delilahs.”

While reports of lynching usually involved African American male victims, the epidemic also extended to other communities of color, including Chinese Americans and Mexican Americans. A recent New York Times article that highlights the histories of Mexican American lynchings in particular reveals another role for American women activists: as contributors to expanded collective memories. That includes the historians upon whose work that New York Times article depends: Professors Monica Muñoz Martínez of Brown University and Laura F. Edwards of Duke University. But it also includes women like Arlinda Valencia, the Texas educator and union official whose ancestors were among the victims of the January 1918 Porvenir mass lynching in which Texas Rangers and ranchers destroyed an entire Mexican American village.

Professor Martínez’s educational nonprofit organization Refusing to Forget has in the half-dozen years since its founding done particularly impressive work recovering those histories and sharing them with audiences of all types. Those efforts include historical markers for particular sites such as Porvenir, traveling and permanent museum exhibitions, and public lectures and conversations. Martínez and her colleagues have discovered a pattern of widespread violence directed not only at individual Mexican Americans, but also and especially at entire communities, with the Porvenir massacre sadly not atypical of these outbursts of collective brutality.

Like Senator Harris, these scholarly and civic historians are working to make the lynching epidemic’s histories more consistently present in our 21st century collective memories. Doing so likewise requires remembering lynching’s complex intersections of race and gender, both in their most destructive and most inspiring forms.

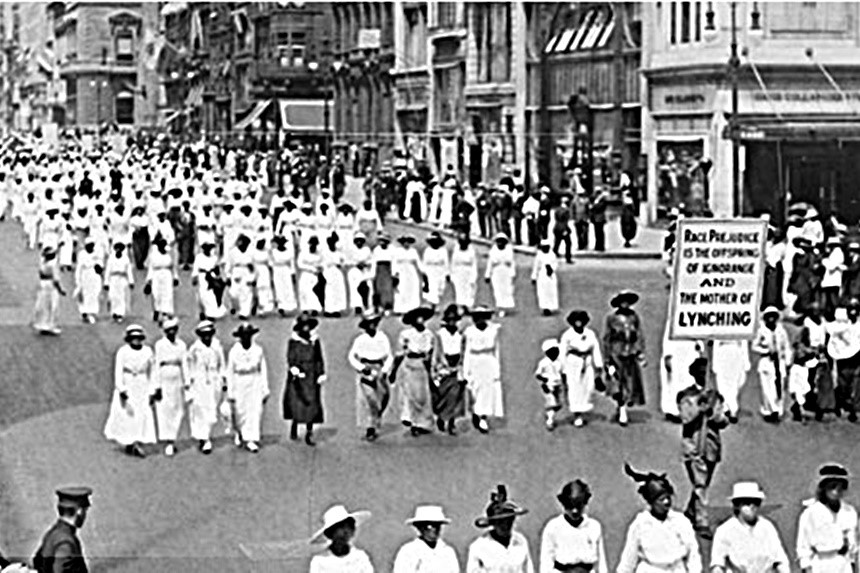

Featured image: The Silent Parade in 1917 in New York City was organized by the NAACP to protest violence toward African Americans. (Library of Congress)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thanks for the good question, George. This is the most overt Saturday Evening Post piece I’ve written on that subject:

https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2019/01/considering-history-myths-and-realities-of-the-mexican-american-border/

This long-ago blog post of mine also addresses the war’s origins:

https://americanstudier.blogspot.com/2012/01/january-25-2012-mexican-american-wars.html

And then I wrote a bit more about it in the Mexican American chapter in my most recent book, We the People:

https://rowman.com/ISBN/9781538128541/We-the-People-The-500-Year-Battle-Over-Who-Is-American

Hope that helps, and feel free to follow up further (including by email: [email protected]),

Ben

Hi Ben, I’m a new SEP subscriber seeking an accurate summary of the origin (precipitating events) of the Mex-America War. What can I read by you on that subject? Thank you. George Miller

to Bobfrommosinee > you are an example of a distorted historical view. The Democratic party of the South was exclusively known as Dixiecrats. The Dixiecrats hated the Republican party of Lincoln, especially after the Civil War. They flipped to the Republican party in the 20th century to align themselves against Democrats, especially the Northern Democrats. Crimes against humanity were a Dixiecrat policy. That hate and distortion carry on today, as tradition, via the Republican party!

To bob frommosinee> You are an example of distorted historical view. You allude to a format political party that called themselves Dixiecrats, as apart from the National Democratic Party. The South hated Republicans because it was the party of Lincoln. The flip happened in the 20th century when Dixiecrats became the new Republican Party. The racism, bigotry, and violence was a Southern phenomenon of the Dixiecrats and their supporters!

Thanks for your comment. To my mind, a central goal of this law is quite the opposite of obfuscation: it’s highlighting dark histories that far too often we have swept under the rug (or at least minimized). In so doing, every side of them will certainly emerge, from political and social ones to their lingering psychological and communal effects. I believe those lingering effects, especially on communities descended from those victims (such as those in Porvenir I mentioned in the article), are one powerful reason why laws like this remain much needed in 2019.

Ben

More Virtue Signalling, Yes To what end? It is illegal to lynch anyone, That is Law, Just Law, We have so many laws on the books that we don’t enforce, Why add another law? How about we enforce the Laws already on the books, Just how much more illegal can you make a crime? Laws do no good if they are not enforced, But we already have murder, be it lynching, shooting, knifing, clubbing, or any other way you can murder someone, So again why add another law when all to often the Law as it stands is not enforced in the first place, Just more Democrat Liberal Virtue Signaling by the same party who established the KKK, Jim Crow, and fought tooth and nale against the Civil Rights Bills, The Democrats/Liberals wanting to obfuscate their long roll in racism, slavery, and segregation long after it does any good for their victims.