This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Native American issues and identities have taken center stage in our political conversations over the last two weeks. On October 9, the Supreme Court issued a last-minute ruling upholding North Dakota’s controversial voter ID act, a law that by requiring voters to have a residential address effectively disenfranchises Native Americans living on the state’s many reservations. And on October 15, Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren responded to Donald Trump’s longstanding attacks on her claims to Native American ancestry by releasing the results of a DNA test featuring “strong evidence” of native heritage.

The Warren story has dominated much of these recent political and media conversations. While that story does offer a potential opening for important discussions of how we define Native American identity and community, it also serves as an unfortunate distraction from the unfolding battle over the North Dakota law and what it means for 21st century Native American rights and communities. And this contemporary battle becomes even more meaningful when placed in the context of the complex and contested history of Native American citizenship and voting rights.

These debates over native sovereignty are longstanding and ongoing. To many scholars and activists, Native American tribes exist outside of (and equal to) the United States. Viewed through that lens, Native Americans should, one day, be able to seek dual citizenship from both their tribe as well as from the United States; their voting rights would, therefore, be tied to that legal and political status.

Despite this status, native citizenship has been tenuous and hard-won. The 14th Amendment to the Constitution, passed by Congress in June 1866, was a watershed moment in the expansion of American citizenship — but not for Native Americans. While it extended protections to all former slaves and their descendants and enshrined into law the concept of “birthright citizenship” for all those born in the United States, this amendment did not apply to all Americans. As a number of subsequent court cases reiterated, the law defined Native Americans as “wards” of the state instead, leaving them outside of this otherwise all-encompassing revision of the national community.

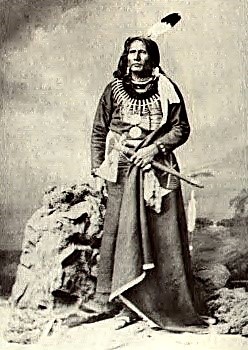

Late 19th century native activists and their allies, however, did not allow this discriminatory exception to go unchallenged. In 1879, Ponca Chief Standing Bear, who had undertaken an extensive protest and speaking tour in order to raise awareness of his tribe’s unlawful and violent treatment at the hands of the U.S. government and military, sued General George Crook. Standing Bear’s suit challenged both the Ponca tribe’s displacement from their Nebraska homeland to an Oklahoma reservation and his personal imprisonment by General Crook (for illegally leaving that reservation in order to stage his protests). After a lengthy and highly public trial, Judge Elmer Dundy ruled in Standing Bear’s favor, noting in his decision that “an Indian is a person” and that “[Indians] have the inalienable right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

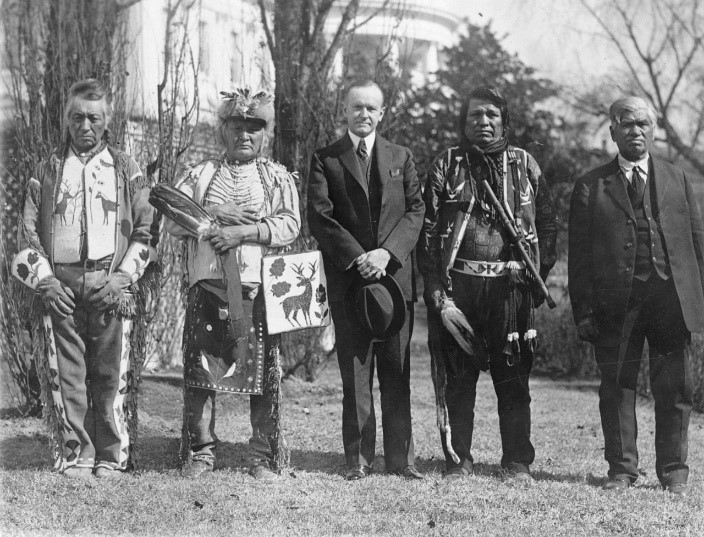

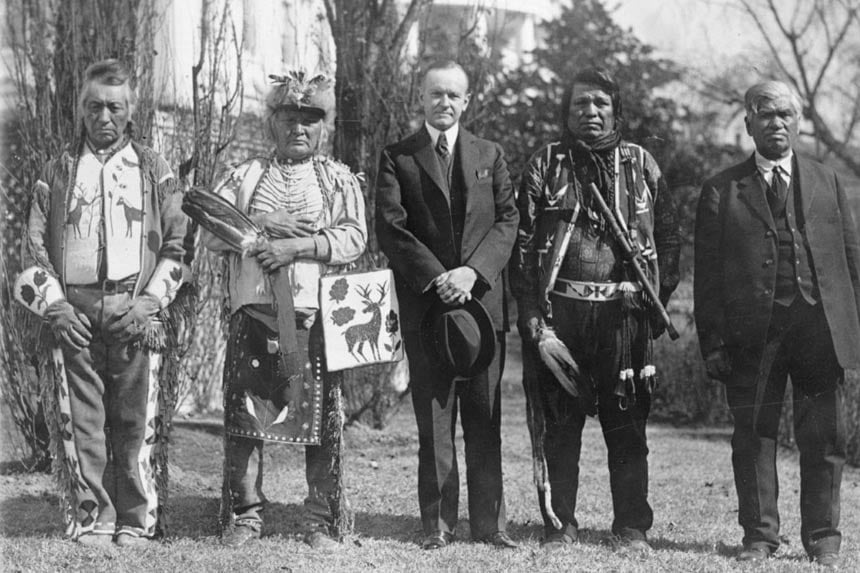

The actions of Chief Standing Bear, along with other victories such as the new (if still circumscribed) opportunities for native citizenship granted by the 1887 Dawes Act, helped push the nation toward a slow, but full recognition of Native American citizenship. This recognition came, mostly, in the form of the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act, which declared “all non-citizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States…to be citizens of the United States,” so long as “the granting of such citizenship shall not in any manner impair or otherwise affect the right of any Indian to tribal or other property.”

Yet as many other groups of Americans throughout our history have long known, full citizenship does not necessarily entail equal voting rights (despite the 15th Amendment’s guarantee that it does). Indeed, through at least the late 1950s, many states maintained laws that prohibited Native Americans from voting. In New Mexico, for example, the state constitution explicitly barred Native Americans living on reservations (the vast majority of the state’s native population) from voting in either state or federal elections. That constitutional discrimination was challenged by native and civil rights activists as early as 1948, but wasn’t amended until 1962.

Even with such changes to state law, coupled with the nationwide protections afforded by the 1965 Voting Rights Act, the battle to ensure and protect Native American voting rights has persisted throughout the 20th century and into the present day. The American Indian Movement (AIM) — too often known only for its controversial occupations and legal cases, such its ongoing fight to free Leonard Peltier from prison — has pursued Standing Bear’s legacy, pushing the struggle for voting rights into our present century. The most recent challenges to the Voting Rights Act and voting access have likewise drastically affected native communities, and are the subject of continued challenges from native activists and their allies, such as the efforts by a number of Arizona tribes to contest that state’s new, labyrinthine Voter ID requirements.

In North Dakota, Arizona, and elsewhere, voting rights and voter suppression efforts have become a central story in the final weeks before the crucial 2018 midterm elections, and rightly so. But the more we can engage with the longstanding debates over and battles for citizenship and civic participation, the more we can recognize the true significance and stakes of these 21st century conflicts.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

The History of the American Native striving to win American reconition as a citizen and to win the right to

Vote was outstanding