For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

The Hand of Fate, which in four years had bounced me like a Super Ball from Minneapolis coed to disco groupie to millionaire’s mistress (one brief shining moment) to Chicago model to New York City and Penthouse magazine, now deposited me into an office shared with the Fury, the Banshee, the Morgan le Fey of the editorial staff, Annie O’Hare.

I was terrified of Annie and her daily tirades, in awe of her ability to string together a chain of curses, utilizing the f-word as adjective, adverb, noun, and verb. I also envied her social life, as I overheard the details over and over. Annie spent several hours every day on the phone recounting her night before, the parties she had attended, the bars she had drunk in, and the men who bought her those drinks, first to the unlucky friends who had missed the fun, then rehashing the whole shebang with the pals who had been with her.

My boyfriend Michael heard daily updates on the office swapping saga and Annie’s and my lack of progress toward a state of detente. Michael was that rare man who did not give advice unless specifically asked for it, but he saw the need to play Henry Kissinger.

After two weeks of Mutually Assured Disregard, Annie and I giving each other the coldest of shoulders, Michael made an unannounced visit, his first to my new office, a territory as fraught with hostility as Checkpoint Charlie.

I had ducked out on some minor editorial task; Michael and Annie were alone. “You and Gay should be friends,” he told her. “We’re having a party on Friday. Come.”

Our apartment, though handkerchief-sized, did have access to a walled courtyard and a dangerously unwalled roof, making it the perfect site for raucous parties, parties that were enlivened by our upstairs neighbor, a novelist who owned a constantly-replenished tank of nitrous oxide. (I tried it only once; the high reminded me too much of my dad’s dental practice to be fun.)

That Friday there were dozens of people crammed everywhere, drinking, smoking, climbing the rickety, crooked stairs to the roof or to sample the novelist’s laughing gas. Annie appeared at the height of the party and the peak of my own drunkenness, materializing in the kitchen just as I realized I had no hope of making it through the crowd to the bathroom.

“Come with me,” I ordered Annie. My last feckless grasp at not being drunk was a desperate need for fresh air; then my brain was swept away by the alcohol and thought it would be better to get that fresh air on the roof than down in the courtyard. We pushed our way up the stairs and on to the roof where my stomach let me know fresh air was the last thing I needed.

I looked at Annie and slurred, “I’m gonna puke. Can you hold my hair?” I stumbled to the edge of the roof, knelt, and hurled. Annie gathered my hair up in one hand and rubbed and patted my back with the other. This is the primal girlfriend gesture that is hard-wired into my DNA; I was as imprinted as a Konrad Lorenz duckling and from then on would have followed Annie anywhere. I wiped my mouth with the back of my hand, turned to Annie and said, “Let’s go find a drink.”

That was the start of a beautiful friendship.

The following Monday, our shared office was transformed from the Gaza Strip to party central, the place where the other editors came to smoke and laugh and gossip and complain, until the crescendoing noise roused our boss, Jim Goode, from his afternoon, post-three-martini-lunch hibernation. His gaunt frame loomed in the office doorway. The other editors fled, and Jim fixed the two of us left with his coffin-maker’s gaze, then slammed the door, leaving Annie and me on our own to laugh and gossip and complain in slightly lowered voices. Eventually Jim tied a rope to our doorknob that stretched along the hallway to his desk, so he could pull our office door shut without having to get up.

Annie and I managed to amuse Jim more than we annoyed him. We tagged-teamed him in his office, four willing ears for his crackpot theories, his rampages against Bob Guccione and the entire Penthouse advertising staff, his hounding by the IRS, CIA, FBI, NSC, and probably the MTA and MOMA too. Annie and I catered to his craziness.

We took turns going down to Con Ed to pay Jim’s overdue-to-the-point-of-cut-off electric bill. We made up false names to call antique dealers, inquiring about the prices of French Belle Époque posters so Jim could spend his money on art rather than utilities. I was assigned to track down a Caribbean holiday destination that would let Jim bring his mutts with him on vacation without the nuisance of a quarantine. Jim ordered me to find out how long a parrot could live; he was convinced that somewhere Tchaikovsky’s parrot was still chirping out “Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy.” I have no idea what Jim did with that information.

Occasionally I got some work done, always in the morning before my own well-lubricated lunches.

Despite Jim’s best efforts to frustrate the Penthouse advertising department (he once pointed his long, skeletal index finger at a startled Penthouse ad salesman and bellowed “Haaaaauuubneer. If I ever see you speaking to this man you are fired”), I turned out nicely photographed, blatantly pandering articles every month on cars, cameras, stereos, motorcycles, and other things I was clueless about.

Jim grudgingly allowed me to assign “real” articles as well. I sent one writer friend off to Nashville to do a history of Gibson guitars, another to report on fly-fishing in the Catskills. I tracked down a reporter at the Miami Herald who could drive to the Keys for an article on the sunken treasure hunter, Mel Fisher; that reporter was Carl Hiassen.

Jim also decided that I was the one who should bring humor into the magazine; the ghastly, unfunny Bill Lee and “Balloonheads” cartoons littered each issue of Penthouse like so much dog dirt.

“Haaauuubner, who writes those funny bits in The New Yorker?”

He was referring to their endnotes, titled “Block that Metaphor!” or “Constabulary Notes from All Over.”

“It was E.B. White, now it’s Roger Angell.”

“Get them. I want them to write for us.”

E.B. White was dead and Roger Angell, his stepson and the finest baseball writer of any generation, did not return my phone calls. Through friends of friends, I found Mark O’Donnell, a Harvard Lampoon alumni, who for a lot of money deigned to write some almost funny pieces for Penthouse before going on to pen the theatrical adaptations of Hairspray and Cry-Baby.

One morning when we were only slightly hung over, Annie and I were called into Jim’s office, summoned by his ground-shaking rumble: “HAAAAUUUUBNER! OOOOHHHARE!”

I didn’t think Jim had a grimmer look in his facial repertoire; I wondered if one of his dogs died or if we needed to come up with a fake alibi for where Jim had been the past year or if a SWAT team of G-men were headed up to the Penthouse office.

“Have you seen this?” he shouted, and showed us the iconic photo of a fluffy white seal, its eyes two black currants peering fretfully out of its snowy head, as if it knew it was about to be clubbed to death. There were also other, bloodier photos.

“Yes, Jim,” I said. “Everyone’s seen it. That was big news like, six months ago.”

“Nobody told me,” said Jim, outraged even more, as if there were a conspiracy to keep cases of seal abuse away from him. “Penthouse has to cover this. This,” his voice got even louder and his office windows shuddered, “this is AN ATROCITY.”

An editorial was penned, bravely taking a stand against beating animals to death. It actually was pretty daring, as I suspect that 99% of Penthouse readers, those who were not legally barred from owning firearms, were avid hunters.

A year after everyone who cared was finished with the seal-clubbing controversy, a Penthouse editorial demanded: “Stop the Murder of Adolescent Seals” even though Annie and I insisted that 1) killing an animal, even a cute one, is not murder, and 2) despite the fact that the most desirable fur came from seals who would be teen-aged in human years, there is no such thing as an adolescent seal, unless up in the frozen north there are pimply, sullen seals whose parents just don’t understand.

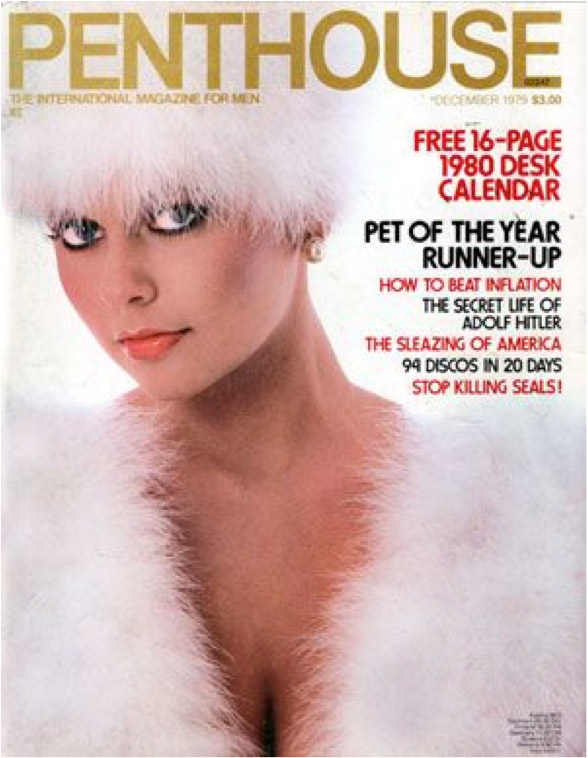

We lost both arguments. At least the space restriction for the cover line shortened it to “Stop Killing Seals.” Not a single editor or reader commented on the fact that the model on this cover was wearing a hat and vest made from the downy white feathers of about 86 dead egrets, maybe even adolescent egrets.

Besides catering to his insanity and paying for his lunches, I kept Jim sweet through regular tribute. Jim got first pick of the booty I received from companies gagging for a mention in Penthouse. Every invitation from a motor company to an all-expenses paid junket I dutifully turned over to Jim: I had no desire to test-drive a sports car (my inability to drive a stick-shift would have blown my cover as Penthouse’s automotive editor), and the only time I had dared get on a motorcycle after seeing my high school pal Betsy Johnson take a spill that shattered a leg and left half her skin on the tarmac was to throw out the first ball at a White Sox home game.

Then I received an invite from Kawasaki, one I was not going to give up without a fight. I timed my visit to Jim’s office for the golden hour, right after lunch, when the martinis were still bubbling in his system, but before the alcoholic crash turned him back into a splenetic ogre.

“Jim, I’ve been invited to Finland by Kawasaki,” Jim held out his hand; I was suppose to render unto Caesar.

“It’s for snowmobiles, Jim. I can ride a snowmobile. I grew up riding snowmobiles. Please, please can I go on this trip?” Annie chimed in from next door; she and I had split a bottle of white Dutch courage at lunch: “Let her go Jim!”

Jim pulled his bloodhound face down even farther with one cadaverous hand, as I struggled to imagine his lanky 6’3” frame hunkered down on a Ski-Doo, with no hat, no gloves, wearing a black leather jacket, his only concession to winter attire, headed toward the North Pole. Jim was probably thinking the same.

“All right, Haubner. This once.” A few weeks later I flew out of JFK on a Finnair jet along with a dozen members of the snowmobile press; until then I had no idea such an august body existed.

Outside of the impenetrable Finnish language, Lapland, in the high northern latitudes, was like coming home to Minnesota, only cleaner. We were put up in a ski lodge that would have been considered the height of modern design in 1967: lots of glass, gleaming pale birchwood, soaring ceilings, and huge stone fireplaces, with that Nordic necessity, a sauna. We landed in Rovaniemi after a day spent in Helsinki with our Kawasaki handlers desperately trying to find something interesting for the snowmobile press to look at besides the inside of a bar.

I had seen the car press drink, I had witnessed the motorcycle press out-drink the car press. The way the snowmobile press could knock ‘em back put those guys in short pants. These were my people, hailing from Bemidji and La Crosse and Michigan’s Iron Range. It was like being surrounded by my hard-drinking Minnesota relatives: men with square heads, ruddy wind-chapped faces, and short blond hair streaked with steel, whose last names ended in -sen or -son, all on a mission to see how much beer they could consume.

“I’ve never been on a trip like this before,” hiccupped my Uncle Cliff’s doppelgänger. “We don’t have to pay for anything? Can I get you another beer?”

The endless, deliciously strong, and free Finnish beer meant that the snowmobile press spent most of the day and all of the night in some state of tipsiness. Despite the drunken party atmosphere and the mildly dirty jokes swapped (“How do you find an old man in the dark? It’s not hard!”) none of these guys made a pass at me. This did not hurt my feelings; I had become the adopted little sister of the snowmobile press.

An unfortunate gutter-side incident following a Don Cuervo tequila party had taught me not to get too drunk at press events. I was mostly sober the first day we went out to ride snowmobiles over those silvered, frosty Finnish slopes during the three hours of a November day, a heavy drift of snow diluting the weak light even more.

I was cocky about my ability to operate a snowmobile. In my Duluth neighborhood a snowmobile was as de rigeur as a lawn mower, and used much, much more often.

I was eight years old when (unknown to my mother) my dad first let me drive the family snowmobile, with my little sister Lani clinging to my back. I quickly perfected the sharp turns that threw her off into the snow, always claiming it was an accident. And the last time I had driven a snowmobile, age sixteen, I was blind from half a hit of mescaline and Boone’s Farm Apple Wine and still made it home in one piece.

But that ride had been eight years ago, and snowmobile technology had come a long way. I almost catapulted off the back myself when I turned the key, gave the right handle a twist. The machine bolted from 0 to 30 mph through the man-high snowbanks. I eased up on the throttle to catch my breath and heard the whoops and hollers of my adopted relations as they raced to see how fast these suckers could go and how much air they could get shooting over the moguls.

I did not set any snow speed records that day, but I did not embarrass myself either. In the role of the little sister, I tagged behind at a distance, having quite enough fun at an almost stately 15 mph while the rest of the snowmobile press contested to see who had the biggest pair.

The sky was purple as a bruise at three, and we were back inside the ski resort holding down a long wooden table and drinking our way till dinner, which was salmon, reindeer, cloudberries, white asparagus, and small squares of dark bread. This was the unvarying menu for every meal.

But who cares about food when there’s beer? And a sauna and a roll in the snow to sober us up so we could start drinking again. After that, conversation was abandoned; since every member of the snowmobile press had spent time in the service, the rest of the night was devoted to determining which branch of the armed forces had the best drinking songs. If I close my eyes, I can picture a WWII ace, eyes as blue as a struck match, grey buzzcut, waving a brown bottle and belting out “HAAPPPY is the day! that an AIRMAN gets his pay! and we go rolling, rolling on!”

The Kawasaki PR agency had cut a deal with the ski resort, which was looking for some good publicity of its own; our minders pushed us to try some of the other winter activities available besides drinking, such as a reindeer-drawn sleigh ride.

I had a vision of myself as Dr. Zhivago’s Lara, wrapped in a fur robe, speeding across the snow in a Disney-esque sleigh. The reality was a knocked-together wood and iron over-sized sled, a mange-ridden reindeer, and a Lapp driver dressed in what would have been a colorful native costume had he not been entirely filth-encrusted; the lines on his face looked like they had been drawn on with charcoal and his long blonde beard was greasy with black dirt. There were no takers for the sleigh ride. We trooped back to the bar, and eventually I said good night after a light-weight consumption of only six beers.

There are few things more horrifying than being woken by a smell. I shot up out of my soft Scandinavian bed like a jack-in-the-box, my eyes watering at the barnyard stink. I couldn’t believe my nose. What rank, animal thing had gotten into my pristine hotel room?

I switched on the lamp: to the left side of my bed was the crusty, sled-driving Lapp, who started cackling when he caught sight of my breasts. He was accompanied by his trusty reindeer; I wasn’t sure which one smelt worse.

On the right side, a few feet away, were the gentlemen of the snowmobile press, red-faced, bursting with laughter at the prank pulled on their adopted little sis. My pal, the WWII aviator, was brandishing the screwdriver he had put to use popping open the sliding door to my room.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Wonderful read! I thoroughly enjoy your adventures, Gay. And, I never will forget your special adventure in Haiti.

I have to admit I DO love that beautiful ’79 Penthouse cover, but feel guilty knowing 86 egret birds were killed for her sexy feather outfit!! And YOU Gay! I’m ashamed of your liberal attitude towards animal abuse of any kind for the sake of human vanity! The Gay Haubner of today would certainly be chastising her earlier self for such misguided, wrong notions wouldn’t she?! I’m glad you mended fences with Annie and became friends. I guess there’s nothing like one woman helping another out when she’s throwing up! That rooftop sounds extremely dangerous to me; no barriers?! I don’t even want to know how high up it was; g– d— !!! I’m glad you got to go to Finland, and did the snowmobiling without too much of an incident, but was worried about your drinking so much, and being the only woman around a bunch of drunk men, on a business trip, in Europe, “off any leash”… Let’s hope chapter 69 doesn’t start out in the way I fear it might. Fahrin, I can only hope all those men broke into her room as just a joke, but I don’t think so. We’ll find out soon. Gay, this whole chapter actually makes ME want a drink, and I don’t ‘drink’! Well, not since 1985 with those Kamikazes at lunch to make the afternoon work time go by faster. Lunches at Flakey Jakes and the Jolly Roger, where my cute young lady co-workers talked me into being a Chippendale’s dancer for Halloween that year! No stripping, just shirtless with the cuffs and collar; too sexy for my shirt that warm day! I’ll have a glass of either Boone’s Farm Apple Wine or Annie Green Springs with you, if you can FIND a bottle of either. Let me know when YOU know, princess.