One song aimed to comfort a young boy dealing with turbulence in his family life. The other song cautioned against the use of violence in social change, yet somehow managed to anger both ends of the political spectrum. The 45 single they came on hit number one in 15 countries and ended 1968 as the number one release of the year in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and the United States. The songs are “Hey Jude” and “Revolution,” and The Beatles released them 50 years ago on August 26th.

The seeds for “Hey Jude” were planted in May of 1968 when John Lennon split with his wife of six years, Cynthia, after beginning his affair with artist Yoko Ono. In June, Paul McCartney went to visit his bandmate’s soon-to-be ex-wife and their son, Julian. On the drive, a song occurred to McCartney that he called “Hey Jules.” It was meant to help make the separation easier on the young boy. Soon after, McCartney changed “Jules” to “Jude,” as he thought that latter was easier to sing and sounded better.

At the same time, Lennon was dealing with his own feelings and his increasing political consciousness. Vietnam War protests in the United States, protests against the communist government in Poland, and the May 1968 campus uprisings in France roiled together in a stew of news coverage that fed Lennon’s interest in expressing his own anti-war sentiments in song. As related in The Beatles Anthology book released in 2000, which collected interviews with the band, Lennon said, “I thought it was about time we spoke about it [revolution], the same as I thought it was about time we stopped not answering about the Vietnamese war.”

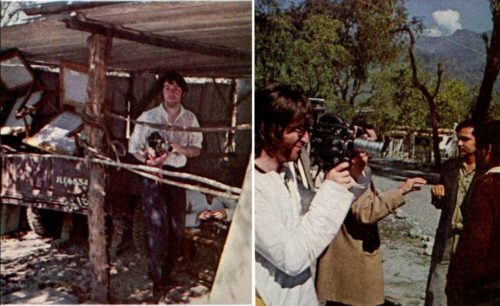

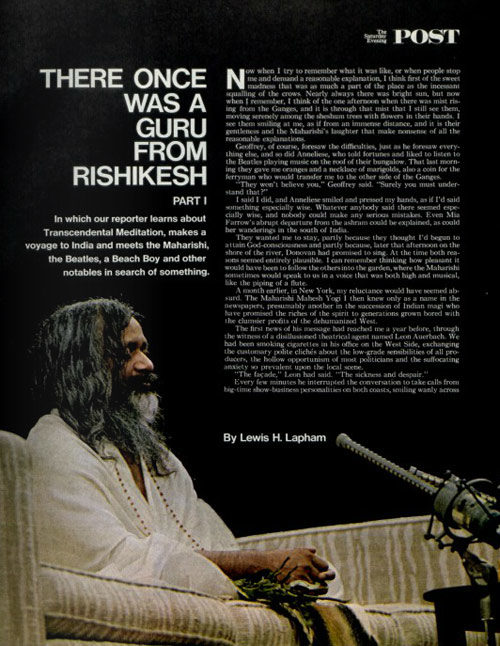

Lennon was also deeply influenced by what he and the rest of the band had experienced with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi earlier in the year. The Maharishi introduced Transcendental Meditation to the West and became the spiritual guide for the band in a period where they publicly rejected drugs in favor of their study of TM. In a pair of stories from 1968 by Lewis H. Lapham, The Saturday Evening Post documented the band’s trip to India along with fellow musicians Mike Love of The Beach Boys and Donovan. Lapham wrote, “Lennon referred me both to their photographs and to their records as diaries of their developing consciousness. In the recent photographs, he said, he hoped people might notice “something going on behind the eyes other than guitar boogie.”

The time in India proved to be a wellspring of creativity for the band. Ringo Starr finished his first tune as a songwriter, and the incredibly prolific Lennon, McCartney, and Harrison would write a total of 18 songs used on The Beatles, aka The White Album and two for the later Abbey Road. During the trip, the band would become disillusioned with the Maharishi over what was perceived to be self-interest and alleged impropriety with another famous student, Mia Farrow, though the group softened their split with him over time. Harrison later went so far as to publicly apologize for the way that The Beatles treated the Maharishi at the time.

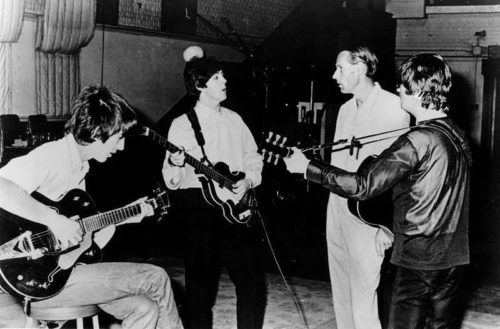

After their time in India, the band returned to the studio in England in May. The recordings of “Hey Jude” and “Revolution” took place from July 9 to July 13 for “Revolution” and July 31 to August 1 for “Hey Jude.” As usual, George Martin sat in the producer’s chair. The version of “Revolution” that backed “Hey Jude” was actually the third version of the song recorded. The first version is the slower, more bluesy take that kicks off Side four on the double-album The Beatles, aka The White Album. The second, experimental version, named “Revolution 9,” is the next-to-last song on that side. Lennon wanted the first “Revolution” to be the single, but McCartney and George Harrison disagreed; McCartney wasn’t sure about the political reception, and both he and Harrison had misgivings about the slower pace.

The compromise became the third, and arguably (perhaps also inarguably) most recognizable, version. The Amplifier/Boss Talk column at the Roland musical equipment company website broke down the recording technique used to achieve the legendary, distorted fuzz-tone guitar that opens the record. They reported that, “According to Geoff Emerick (the studio engineer for that session), he had John Lennon and George Harrison running their guitars directly into the mixing desk. The guitar tone is a result of one channel on the mixing desk being run into another. Both of these channels were driven well beyond their normal operating capacity. Bad news for the desk (it could have overheated and caused permanent damage), good news for guitar tone history!”

The official promotional film of “Revolution” by The Beatles.

Though the band would, excuse us, come together on the idea of “Hey Jude” being the A-side, they still needed to record it. For two nights prior to the official session, the band rehearsed the song, laying down 25 takes. During the actual recording, the band did four full takes, but chose the first one as the master for the song. Additional instrumentation and background vocals were added in the overdubbing phase, as was the final coda, which featured a 36-piece orchestra (producer George Martin provided the scoring for their parts). The final version of the single clocked in at 7 minutes and 11 seconds, a mammoth for its time.

“Hey Jude”

Many musicologists and critics have tried to dissect the appeal of “Jude” over time. The sing-along aspect certainly contributes to its popularity. It’s also a classic slow-build song in that it starts simply (McCartney on the piano, singing) as the other pieces gradually come in and build to the grand climactic combination of orchestra and stadium-pleasing “Na Na NA Na Na Na NA” refrain.

Music comes and goes, but The Beatles stubbornly refuse to fade. Dozens of their songs remain staples across a variety of radio formats, and surviving members McCartney and Ringo Starr have vital, ongoing concert and recording careers. The band was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1988, and each member has received an individual induction (as has Martin and their original manager Brian Epstein). As for “Hey, Jude,” Rolling Stone ranked it at number eight on their “500 Greatest Songs of All Time.” It may be, without exaggeration, one song that nearly everyone on the planet knows. It certainly seemed that way when McCartney performed it near the end of the opening ceremony of the 2012 Olympic Summer Games in London. To create music that cuts across all cultures and political differences . . . maybe that was the biggest revolution of all.

Featured image: Shutterstock.com

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Hey Jude is a catchy song marred by McCartney’s pseudo profound lyrics. Pseudo profound lyrics ruin a lot of the Beatles’ stuff for me. No wonder the previous generation of songwriters loathed them. It wasn’t the music, it was the shamefully sloppy lyrics.

The world is losing legendary music icons that really plays the instrument and truly gifted with great voice. The Beatles is just one of those. Their music are so well thought of and studied. Instrumentals and lyrics that lift your spirit. Thank you Saturday Evening Post for this article.

This is yet another interesting trip back to 1968 this year via the POST in a well researched feature. We see how ‘Hey Jude’ and ‘Revolution’ came to be with various factors basically colliding at the same time: the Vietnam War, John’s divorce and lessons learned in India.

I found the part about the mixing desk to be interesting too. Both versions of ‘Revolution’ are appealing depending on what mood I’m in; not unlike Del Shannon’s ‘Runaway’. You have the original, Bonnie Raitt’s beautiful, slow version from ’77, then Del’s “Crime Story” sophisticated hard-edged remake from 1986 featuring that sexy saxophone.

Thanks for the links to both songs. ‘Hey Jude’ is a crowd pleaser as the experts mention, partly because of the mentioned refrain. It just goes on about 2 minutes too long, unfortunately.

In a way the Beatles are overshadowed/overpowered by these 2 songs to this day, just as Sargent Pepper still overshadows Magical Mystery Tour and The Yellow Submarine. Radio stations are largely responsible for this over the years as well. (The Car’s ‘My Best Friend’s Girl’ and ‘Just What I Needed’ from ’78, are treated as THEIR only songs 40 years later. ‘Candy-O’ from ’79 is like a ‘Best Of’ album, even though it wasn’t.)

Many so-called Beatles fans also don’t acknowledge their solo career work, much of which matches or excels their Beatles work. Fans like to keep musicians pigeonholed. How dare Ringo Starr do the beautiful Doo-Wop classic ‘Only You’ in ’74, or Robert Plant do that Honeydripper’s album in 1984 with ‘Sea of Love’, also Doo-Wop, and also far better than the original.

So we have to see these Beatles songs as only part of a much larger collective tapestry of work; one that shouldn’t be left in the dark shadows of ignorance and neglect, especially by those ‘claiming’ to be fans. There was life after the Beatles, and a good one at that.