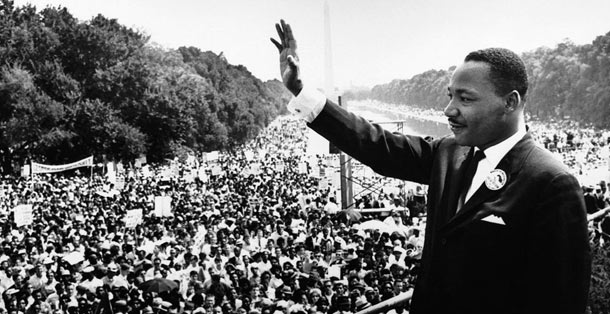

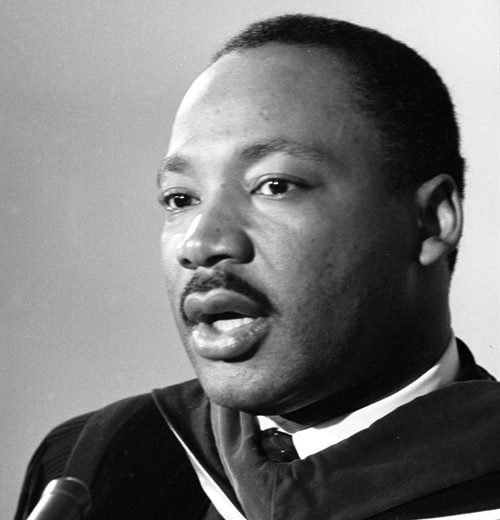

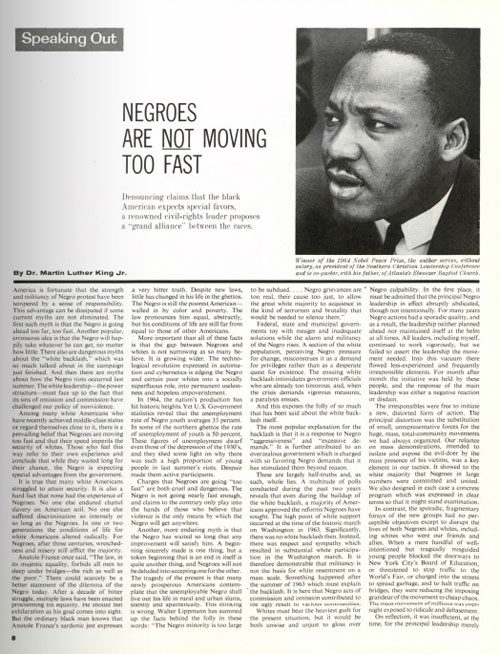

The March on Washington in 1963 seemed to herald a new era in civil rights. But in the following year, the persistence of “grinding poverty” drove some Black Americans to violence. Was progress toward equality and integration taking place too quickly, as some believed? In 1964, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., responded to that question in the essay excerpted below.

Despite new laws, little has changed in his life in the ghettos. The Negro is still the poorest American walled in by color and poverty. The law pronounces him equal, abstractly, but his conditions of life are still far from equal to those of other Americans. The gap between Negroes and whites is not narrowing as so many believe. It is growing wider.

Charges that Negroes are going “too fast” are both cruel and dangerous. The Negro is not going nearly fast enough, and claims to the contrary only play into the hands of those who believe that violence is the only means by which the Negro will get anywhere.

Another, more enduring myth is that the Negro has waited so long that any improvement will satisfy him. A beginning sincerely made is one thing, but a token beginning that is an end in itself is quite another thing, and Negroes will not be deluded into accepting one for the other. The tragedy of the present is that many newly prosperous Americans contemplate that the unemployable Negro shall live out his life in rural and urban slums, silently and apathetically. This thinking is wrong.

Federal, state, and municipal governments toy with meager and inadequate solutions while the alarm and militancy of the Negro rises. A section of the white population, perceiving Negro pressure for change, misconstrues it as a demand for privileges rather than as a desperate quest for existence. In 1963, at the time of the Washington march, the whole nation talked of Negro freedom, and the Negro began to believe in its reality. Then shattered dreams and the persistence of grinding poverty drove a small but desperate group of Negroes into the swamp of senseless violence. Riots solved nothing, but they stunned the nation. One of the questions they evoked was doubt about the Negro’s attachment to the doctrine of nonviolence.

Is the dilemma impossible of resolution? The best course for the Negro happens to be the best course for whites as well and for the nation as a whole. There must be a grand alliance of Negro and white. This alliance must consist of the vast majorities of each group. It must have the objective of eradicating social evils which oppress both white and Negro. It is not only more moral for both races to work together but more logical.

The majority of Negroes want an alliance with white Americans to tackle the social injustices that afflict both of them. If a few Negro extremists and white extremists manage to divide their people, the tragic result will be the ascendancy of extreme reaction which exploits all people.

Our nation has absorbed many minorities from all nations of the world. Many reforms were necessary — labor laws and social-welfare measures — to achieve this result. We accomplished these changes in the past because there was a will to do it, and because the nation became greater and stronger in the process. Our country has the need and capacity for further growth, and today there are enough Americans, Negro and white, with faith in the future, with compassion and will to repeat the bright experience of our past.

—“Negroes Are Not Moving Too Fast” by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., November 7, 1964

This article appears in the March/April 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now