“We look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms. The first is freedom of speech and expression. The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way — everywhere in the world. The third is freedom from want … everywhere in the world. The fourth is freedom from fear … anywhere in the world.”

—President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Message to Congress, January 6, 1941

Inspired by Franklin D. Roosevelt’s famous “Four Freedoms” speech to Congress on January 6, 1941, on the eve of World War II, Norman Rockwell wanted to contribute to the war effort by creating paintings that depicted each one.

The artist struggled with how best to visualize the abstract concepts. “I juggled the ‘Four Freedoms’ around in my mind, reading a sentence here, a sentence there, trying to find a picture,” he later recalled. “But it was so high-blown. Somehow I just couldn’t get my mind around it.”

One night in bed, Rockwell was mulling over the proclamation, getting more discouraged as hours ticked by. “I suddenly remembered how [neighbor] Jim Edgerton had stood up in a town meeting and said something that everybody else disagreed with,” Rockwell said. “They had let him have his say. No one had shouted him down. I thought — that’s it. Freedom of Speech — a New England town meeting. Freedom from Want — a Thanksgiving dinner. I’ll express the ideas in simple, everyday scenes … in terms everybody can understand.”

Excited and confident, Rockwell rolled up his sketches and boarded a train for Washington, D.C., to visit the government’s propaganda department, the Office of War Information, proposing that the illustrations be made into patriotic posters that could be sold to raise funds for the war effort. “I showed the Four Freedoms to the man in charge of posters,” Rockwell said, “but he wasn’t even interested.” On his way back to Vermont, the discouraged artist stopped in Philadelphia to discuss future projects with Post editor Ben Hibbs. In passing, Rockwell mentioned his Washington trip, explained what the series was about, and then showed him the sketches. Hibbs loved the idea, telling the artist, “Norman, you’ve got to do them for us. … Drop everything else, just do the Four Freedoms.”

Rockwell spent seven months painting the Four Freedoms, which were published in four consecutive issues of the Post, starting on February 20, 1943, accompanied by essays by four distinguished writers — Booth Tarkington, Will Durant, Carlos Bulosan, and Stephen Vincent Benet. The paintings were a phenomenal success, with the Post receiving 25,000 reprint requests. A few months later, the government changed its tune, and in May 1943, the Post and the U.S. Treasury Department launched a joint fundraising campaign, sending the paintings on a 16-city national tour. More than one million people attended the exhibition that raised an astounding $132 million.

Now hanging in the Norman Rockwell Museum, the iconic paintings capture the freedoms we enjoy as Americans and the cherished ideals that unite us — timeless reminders of what we have and what we have to lose.

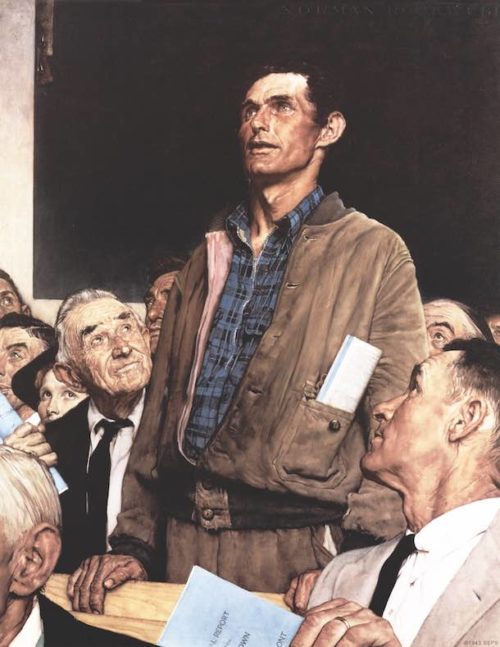

Freedom of Speech: Rockwell started the first painting in the series at least four times. He initially depicted an entire town meeting full of people, with one man standing up in the center of the crowd talking, but later felt “there were too many people in the picture.” He altered the composition significantly, tightening the focus on the speaker, now positioned in front of a blackboard, as townspeople listened respectfully to the speaker’s words.

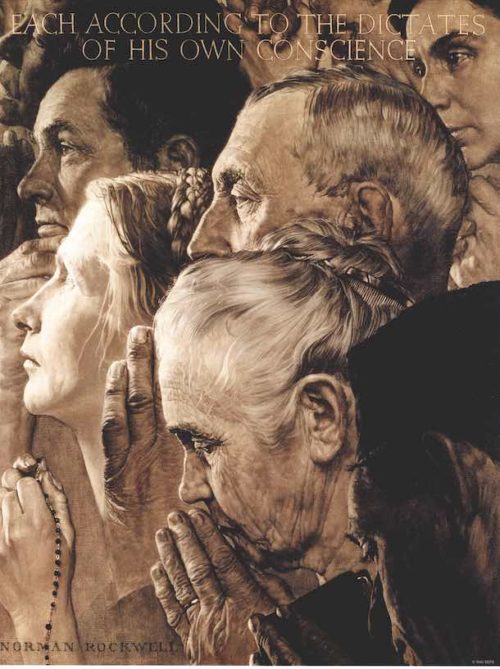

Freedom of Worship: The original painting was set in a barbershop, with patrons of various races and religions patiently waiting their turns. “I wanted it to make the statement that no man should be discriminated against regardless of his race or religion,” Rockwell said. Ultimately, Rockwell rejected that scene as ambiguous. Instead, his finished composition groups faces and hands — a mélange of different cultures — in prayerful contemplation, bearing the legend, “Each according to the dictates of his own conscience.”

Freedom from Want: One of Rockwell’s most famous and beloved works, Freedom from Want became an iconic representation of America’s quintessential national holiday, Thanksgiving. To create the scene, he grouped members of his own family and friends around a dinner table for a holiday meal. After two difficult paintings (Speech and Worship), this one came easy: “Mrs. Wheaton, our cook (and the woman holding the turkey), cooked it, I painted it, and we ate it.”

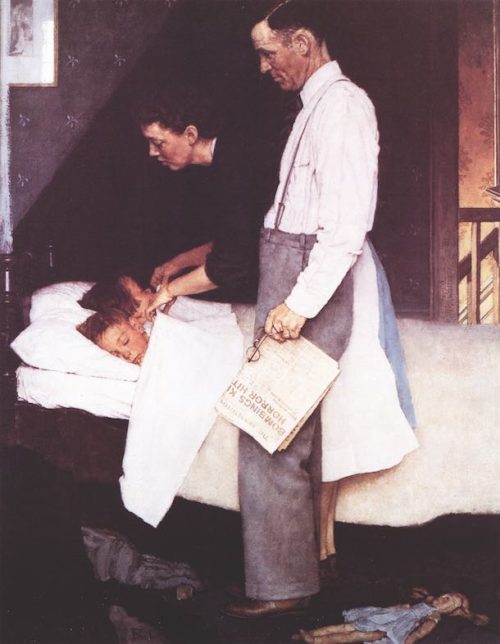

Freedom from Fear: The last in the series depicts children, oblivious to the mounting conflict in the world, resting safely in bed as their parents look on. The serenity of the scene is belied by the newspaper’s bold headline, “Bombing” — a reference the 1940–1941 blitz in London. Rockwell said the idea he hoped to convey was this: “Thank God we can put our children to bed with a feeling of security, knowing they will not be killed in the night.”

Rockwell’s Lasting Legacy

by Abigail Rockwell

We are living in chaotic and even alarming times, but here’s the tremendous gift: We are compelled to go within — so much outside of ourselves is beyond our control — to discover what our true values are — what is really important to us, for our families and our lives. Everything becomes clear in times of crisis. All of us are now urged to revisit the Four Freedoms and what they mean to us. Freedom of Speech (and the Press) is more relevant and vital than ever before; Freedom from Want — the polarity of the haves and the have-nots is starkly apparent and pressing; Freedom of Worship as everyone’s faith is being tested, judged, and at times viciously condemned; and Freedom from Fear haunts all of us as we attempt to gather greater strength, courage, and renewed purpose in the face of escalating troubles around the world.

The process of painting the Four Freedoms ushered in a new phase in my grandfather’s work; a greater sense of purpose, refined technique, and heightened storytelling began to inform his art from then on.

The great studio fire that occurred shortly after he completed Four Freedoms — a blaze that destroyed his entire studio and its contents, including the collection of his own work — forced him to immediately let go of the past and start all over again in the harsh light of an inestimable artistic and personal loss. But he embraced it, moved to a less isolated home on the West Arlington town green, and became very close with his neighbors — the Edgertons and the entire community in Vermont — which also greatly benefited his work and life.

Without his seven-month struggle in painting the Four Freedoms and the subsequent studio fire, the period of Norman Rockwell’s masterpieces in the late ’40s to mid-’50s simply would not have occurred.

To read the complete Four Freedoms essays, visit saturdayeveningpost.com/fourfreedoms.

This article is featured in the January/February 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Instructions state “Required fields are marked * ”

The comment field is not so marked – why then is it required to sign in to your newsletter?

This is my comment. Thank You,