This is an abridged version of an article that appeared in the in the October 27, 1962, issue of The Saturday Evening Post. You can read the complete original article in the flipbook, below.

This article and other features about the stars of Tinseltown can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Golden Age of Hollywood. This edition can be ordered here.

John (Duke) Wayne had just come back from his annual checkup at the Scripps Clinic in Southern California. Considering his age and, as he put it, “the pounding you have to take in this business,” the world’s number-one box-office movie star was in passable shape.

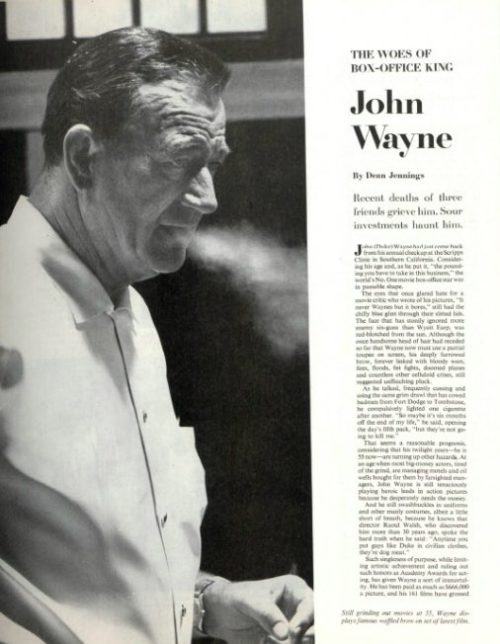

The eyes that once glared hate for a movie critic who wrote of his pictures, “It never Waynes but it bores,” still had the chilly blue glint through their slitted lids. The face that has stonily ignored more enemy six guns than Wyatt Earp was red-blotched from the sun. Although the once handsome head of hair has receded so far that Wayne now must use a partial toupee on-screen, his deeply furrowed brow, forever linked with bloody wars, fires, floods, fist fights, doomed planes and countless other celluloid crises, still suggested unflinching pluck.

As he talked, frequently cussing and using the same grim drawl that has cowed badmen from Fort Dodge to Tombstone, he compulsively lighted one cigarette after another. “So maybe it’s six months off the end of my life,” he said, opening the day’s fifth pack, “but they’re not going to kill me.”

Although he may not be worried about his health, his twilight years — he is 55 now — are turning up other hazards. At an age when most big-money actors, tired of the grind, are managing motels and oil wells bought for them by farsighted managers, John Wayne is still tenaciously playing heroic leads in action pictures because he desperately needs the money.

Such singleness of purpose, while limiting artistic achievement and ruling out such honors as Academy Awards for acting, has given Wayne a sort of immortality. He has been paid as much as $666,000 a picture, and his 161 films have grossed about $350,000,000, a record that Hollywood historians expect to stand for all time. “Most films are money in the bank,” one associate says, “when you’ve got good ol’ Duke in there banging away.”

But if Duke does well for others, he has trouble doing well for himself. The recent deaths of three close friends have sapped him, and despite the small fortune he has made, Wayne today is just barely breaking even. His distress extends to the world at large, which he considers to be run by a band of fuzzy minds who probably would have sneaked out a back archway at the Alamo.

Possibly to dispel the gloom brought on by those thoughts, Wayne absorbs a formidable amount of alcohol without getting drunk. In every angry moment he risks a flare — up from the ulcers that plagued him in earlier days, and he is so sensitive about the printed word that he now insists — though it did not apply to this article—on approving every line written about him before granting an interview.

A Rough Reputation

One time, Frank Sinatra had hired screenwriter Albert Maltz, one of the “unfriendly 10,” who served jail sentences for contempt of the J. Parnell Thomas House Un-American Activities Committee, and reporters called Wayne for an opinion. Wayne snapped, “I don’t think my opinion is too important. Why don’t you ask Sinatra’s crony, who’s going to run our country for the next few years, what he thinks of it?”

Wayne’s dig at President Kennedy appeared in print and generated so much heat that Sinatra was forced to fire Maltz. Shortly afterward at a Hollywood benefit show, Sinatra stalked off the stage when Wayne came up to the microphone.

“Frankie,” Wayne said to Sinatra later, “What the hell did you walk away from me for?”

“Well, you cried,” Sinatra said. “You blasted off your mouth.”

“You mean the Maltz thing?”

“Yes,” Sinatra replied.

“You want to talk about it?” Wayne asked him in reply.

“Some other time,” said Sinatra. “Duke, we’re friends, and we’ll probably do pictures together. Let’s forget the whole thing.”

This is typical of Wayne. Although he sits on the far right, he has many friends among Hollywood liberals. When Robert Ryan’s wife and children received a bomb threat last year, because Ryan had read part of Robert Welsh’s John Birch Society “Blue Book” on a Los Angeles radio station, Ryan and Wayne were in France, working on the Longest Day. Wayne was the first to offer help. He wanted to rush home and help Ryan find the would-be bombers and beat them to a pulp.

In recent years, Wayne has indeed had many things on his mind, most of them calculated to bring on insomnia. Although he shouldn’t have to worry about being overdrawn at the bank, Wayne claims his millions have mysteriously slipped away in the night.

“I suddenly found out after 25 years,” he said sadly, “that I was starting out all over again. I just didn’t have it made at all. Until last year I had a business manager who didn’t do anything illegal, but we were involved in many unfortunate money-losing deals. I would just about break even if I sold everything right now.”

Wayne says he invested $1,200,000 of his own money — all the cash he could scrape up — in producing the ill-fated Alamo. Friends, including Texas millionaire Clint Murchison, also invested huge sums of money. Wayne is confident they won’t wind up losers, but the picture must gross $18,000,000 before there is a profit, and Wayne’s chances of getting all his money back are about the same as falling an inside straight.

Despite it all, Wayne continues to live well. His home is a five-acre estate in Encino, where the hot San Fernando Valley sun warms an Olympic-size swimming pool and vast reaches of green grass. An electric eye controls the gate into the long, curving driveway to the big ranch-style house. Inside, Wayne and his third wife, former Peruvian actress Pilar Palette, are waited on by three servants, also from Peru.

To keep up all the payments, Wayne works in picture after picture. Recently he has been making them at a rate of three a year. In the past 12 months he has appeared in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Hatari, and The Longest Day. He has just finished Donovan’s Reef for Paramount, and he will make three more pictures in 1963. He has also joined the cast of The Greatest Story Ever Told.

Wayne’s frenetic filmmaking may eventually cure his money ills, but his deeper woes defy remedy. Gone are three of his closest friends: actor Grant Withers, who committed suicide; actor Ward Bond, who dropped dead of a heart attack in 1960 at the height of his TV fame in Wagon Train; and Bev Barnett, Wayne’s longtime press agent. “Oh, God,” Wayne said of Barnett’s death, “that’s a tough one.”

The deaths of these close friends, the near death of his 74-year-old mother, Mrs. Sydney Preen of Long Beach, in an auto accident, and two wrenching divorces have drained some of the violence out of Wayne. In the early days of his career Wayne’s muscular figure (six feet four, 220 pounds) was a challenge to folks who thought they could lick him. “I found out once,” he says, “that some of the toughest men I knew, when they really get mad, have a little smile and a look and they’re talking low. This is the way I get mad. But it happens very seldom anymore. I really like people. Unless people go out of their way to insult me, they’re going to have a hard time having any trouble with me. My last street fight was with a couple of boilermakers, but that was years ago.”

Some subjects still trigger a flare-up. One is politics. Television is another. “Television,” Wayne says, “has a tendency to reach a little. In their westerns they’re getting away from the fact that those men were fighting the elements and the rawness of nature, and didn’t have time for this couch work. For me, basic art and simplicity are most important. Love. Hate. Everything right out there without much nuance.”

This article and other features about the stars of Tinseltown can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Golden Age of Hollywood. This edition can be ordered here.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

It took a lot of courage and humility on John Wayne’s part to be so candid in sharing his fears, concerns and losses with Dean Jennings for the Post in 1962.

He had an awful lot to deal with, all at the same time which is always difficult. When it’s on a grand scale like this, all the more so. Showing the true grit of John Wayne, he got through this and triumphed in the years ahead. This isn’t only a great feature on Wayne, it’s something we can all learn from, and never give up when times are tough with pain and suffering.