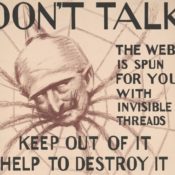

Armies lost the ability to conceal themselves when the airplane appeared above the battlefields of World War I Europe, so soldiers came up with a defense against aerial snooping, and introduced a new word to the English language.

“Camouflage” by Will Irwin, September 29, 1917

It is pronounced, at present, French fashion, like this — “cam-oo-flazh.” In the theatrical business it signified makeup. The scene painters of the Parisian theaters carried it with them to the war and fixed it in army slang; for just about that time the armies of Europe began to introduce a new branch of tactics into warfare. By the end of the first year, most of the guns and motor transports used near the line were striped with greens, browns, dull yellows; sometimes with pinks and blues. But the stripes were not regular. All lines of union were wavy or broken. Nor did the colors meet each other sharply. For a little distance they were blended. It looked more, perhaps, as though someone had poured a few bucketfuls of paint, hit or miss, over guns and transports.

It is pronounced, at present, French fashion, like this — “cam-oo-flazh.” In the theatrical business it signified makeup. The scene painters of the Parisian theaters carried it with them to the war and fixed it in army slang; for just about that time the armies of Europe began to introduce a new branch of tactics into warfare. By the end of the first year, most of the guns and motor transports used near the line were striped with greens, browns, dull yellows; sometimes with pinks and blues. But the stripes were not regular. All lines of union were wavy or broken. Nor did the colors meet each other sharply. For a little distance they were blended. It looked more, perhaps, as though someone had poured a few bucketfuls of paint, hit or miss, over guns and transports.

This article is featured in the September/October 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now