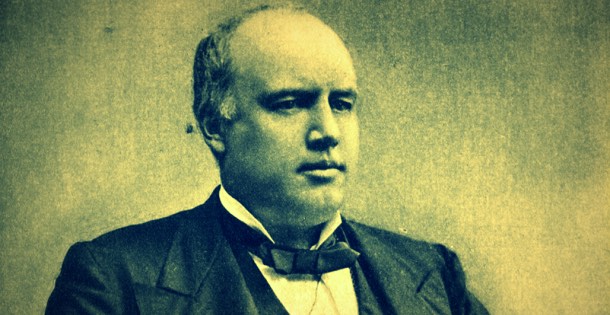

Robert Ingersoll, the 19th-century American thinker and speaker, was born on this day in 1833. Long before talking heads began bloviating nonstop on cable news, the public would line up to see the most impressive orators of the day. Despite social sea changes in the 20th century, this Post article from more than 90 years ago shows that the makings of a good public speech are timeless.

In “The Art of Public Speaking,” a 1924 analysis of oratory, Albert J. Beveridge outlines the traits of an effective speaker. According to Beveridge, an aptitude for communication enters into it, but — as with any art — orators must gain an understanding of the form and its history if they wish to be successful.

As to composition and structure of the speech, the rules of that art may be summarized thus:

Speak only when you have something to say.

Speak only what you believe to be true.

Prepare thoroughly.

Be clear.

Stick to your subject.

Be fair.

Be brief.

Beveridge commends Robert Ingersoll as a “master of the art” and recalls seeing the Civil War veteran speak as a 20-year-old: “In short, everything about Colonel Ingersoll was pleasing, nothing was repellent — a prime requisite to the winning of a cordial hearing from any audience, big or little, rough or polite.” The writer applauds Ingersoll’s conversational tone and natural gestures.

Beveridge omits the topic of Ingersoll’s oration. In fact, Ingersoll was known as “The Great Agnostic” who often criticized religion and spoke on history and humanism. Few sound recordings of Ingersoll exist, but a short speech, “On Hope,” was recorded on gramophone by Emile Berliner in 1897. Ingersoll speaks in a casual, steady rhythm, saying,

I am not trying to destroy another world, but I am endeavoring to prevent the theologians from destroying this. The hope of another life was in the heart long before the sacred books were written and will remain there long after all the sacred books are known to be the work of savage and superstitious men.

Ingersoll’s ideas about secular humanism were not always received well, but his style of calm oration afforded him the best possible response from a 19th-century Midwestern audience. Along with Daniel Webster, Wendell Phillips, and Patrick Henry, Beveridge named Ingersoll “one of the four greatest public speakers America has produced.”

The weightiest advice in Beveridge’s article is his insistence on sincerity and honesty from a speaker, because “ignorance is dangerous:”

First, last and above all else, the public speaker is a teacher. The man or woman who presumes to talk to an audience should know more about the subject discussed than anybody and everybody in that audience. Otherwise, why speak at all? How dismal an uninformed speech! When coupled with sincerity, how pitiable! And how poisonous! For that very ingenuousness often causes the hearers to believe, for the time being, that the speaker knows what he is talking about.

Beveridge’s emphasis on honesty and research came before instant fact-checking and smart phones, yet the importance of his words endures. Whether oration is given on a soapbox, into a gramophone, or livestreamed online, words still matter.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now