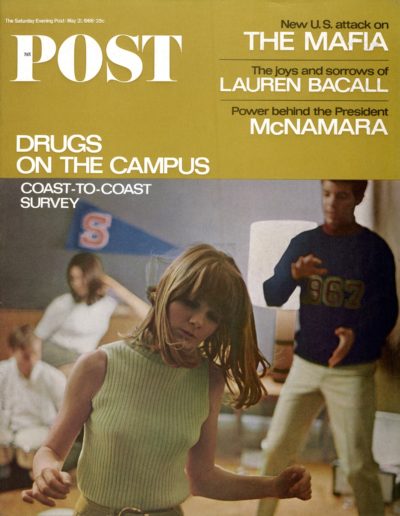

[Editor’s note: This two-part story was originally published in the Post as “Drugs on the Campus” on May 21 and June 4, 1966. We republish it here as part of our 50th anniversary commemoration of the Summer of Love. Scroll to the bottom to see this story as it appeared in the magazine.]

Part 1

At Harvard, a student stands beneath a bulletin board that offers cars and typewriters for sale, and points out a cryptic message: “Ride wanted to Antioch — this weekend. Will pay expenses.” This, the student claims, is a general plea for marijuana. The offer to pay expenses is a declaration of solvency. A local pusher will phone the number given and make an appointment.

At the University of Wisconsin, where single males often appear on campus to search out dates, a student enters a women’s dormitory and cries up the stairs, “Anyone want a date? I’m from the U. of C.” It’s a typical-enough moment, except that “U. of C.” stands for the University of Chicago, where some Wisconsin students claim to get their marijuana. The knowledgeable girl who responds to this mating call will show up with $25 and an empty handbag.

On the University of Texas campus, one student sells incoming freshmen annotated maps of the campus. For five dollars you can buy a special map with a black “x” drawn in gothic lettering. On this spot the owner will usually find a patch of marijuana, ready for harvesting.

At the University of California at Berkeley, a student makes periodic trips to Mexico with a trunkful of scuba tanks. Once across the border, he purchases marijuana on the easy Mexican black market, and sets about replacing the compressed air with marijuana smoke. When he returns to Berkeley, he sells the tanks, “just like you would sell a keg of beer to some kids having a party.” The tank is passed around like a marijuana pipe, each user inhaling from the mouthpiece. The method is inefficient, but it is considered colorful.

Marijuana has become this generation’s illicit pleasure. In the ’20s, illegal booze parties took place on ivy-covered campuses on which golden Scott Fitzgerald characters frolicked. In the ’50s, when the Kinsey Report stunned a “Puritan” America, college students were experimenting with sex — and bragging about it. Now it is drugs. On campus after campus, scandal and denials follow the revelation that students are “turning on.” Administrators deny it, and alumni doubt it. But the police know about it. Health officials and school psychiatrists are aware of it. The students themselves are not only sure it exists but they can usually tell you where to find the action.

In Harvard Square, you can obtain marijuana within 30 minutes. Near Columbia University, on Upper Broadway, it takes 20 minutes. From Princeton’s Nassau Street to Minnesota’s Dinkytown to Seattle’s University Way, students are experimenting with non-addictive drugs.

Marijuana is, after alcohol, the most popular intoxicant in the world. Scientists call the plant Cannabis savita. Indians call it bhang, Turks hashish, Chinese ma, Moroccans kef, Mexicans marijuana. Most Americans who have used the drug call it pot, though other names — boo, grass, maryjane, stuff — appear as rapidly as the cult tires of the old words.

The long-haired element on campus (those who are variously called “ethnic,” “beatnik,” “folkie” or “fringie”) is often a major source of marijuana, but it is a grave mistake to assume that these students are the only ones who use drugs. Drugs have begun to invade “respectable” areas of campus life, like Fraternity Row. Special names are given to locally grown marijuana — Brooklyn green, Berkeley boo, Wisconsin weed, Kentucky bluegrass, Kansas standard. When so many are certain that the law is wrong, illegal activities become a huge game like the activities many Americans indulged in during prohibition. When you considered liquor harmless and fashionable, the fact that it was illegal seemed laughable. College students today feel that way about marijuana. Pot smokers, to a man, find their vice “enjoyable” and “harmless.” They deny that student users graduate to heroin.

To many college students, marijuana is illegal but safe, and heroin is dangerous, and therefore uncool. The few students who use heroin are referred to as “sickies” by even the most Bohemian of students. Most important, they suddenly become “square.” They have allowed the body to dominate, and they have exhibited vulnerability and dependence; cool people do not depend. Most important, with their glazed faces and drug obsession they scare even the habitual marijuana users, or “potheads.”

Police estimate that 30 percent of all heroin addicts begin with marijuana — but these statistics simply do not apply to the college scene. A former narcotics commissioner at the New York City Health Department has reported that 90 percent of the city’s heroin addicts are school dropouts, and concludes that few college students are likely to use addictive drugs. The slum drug addict, caught in a hopeless, dismal existence, turns to drugs as an escape from slum life, but our student population is the most pampered and worried-about in history.

The question of the danger or safety of marijuana, however, is by no means settled. By general medical agreement, marijuana is non-addictive. It almost never leaves a hangover. It is less damaging, physically, than alcohol. Some psychiatrists and doctors believe that the drug should be legalized, and eventually will be. They predict that marijuana will someday rival liquor as the prime social intoxicant.

Other experts, however, point out that marijuana may be “psychologically” habit-forming, although it is probably less so than either tobacco or alcohol. Some doctors believe that, taken in excessive quantities, marijuana can produce brain and lung damage. Most experts say that, for people who are already emotionally disturbed, marijuana sometimes uncovers psychological problems. And some doctors see dangers in the very fact that marijuana users can still function while high. One doctor asserts: “The user will be able to perform feats on marijuana, while he would probably just pass out on liquor. For instance, he can drive a car under the influence of marijuana, even though his judgment is impaired. And he can commit acts of violence under marijuana, since it sometimes creates a sense of ultimate power that can be dangerous to the abnormal personality. Liquor does this also, but it also makes it hard for the individual to do physically what he may feel like doing emotionally.”

The reasons students use marijuana vary from group to group, but the great majority claim they take the drug simply because it gives them pleasure. Some experimenters give up after one or two times, because “It made me nauseated,” or “It didn’t do anything for me,” or “It’s like parachute jumping. Once is enough.” But marijuana users claim that a pleasurable experience always comes with practice. Medics are not so sure. One doctor says, “It’s a very mild psychedelic [psychedelics are drugs which change perception and disorient the mind]. It just gives you a head start on yourself. For many, it does nothing at all, and they have to fake it.” Boston police report one “pot party” in which authorities found a group of teen-agers who seemed to be very high on marijuana. But little could be done, once the police realized they had confiscated ordinary cigarette tobacco, bought at marijuana prices from a clever pusher.

Students who can get high simply by suggestion form one end of a continuum at whose other extreme is the experimenter who gets nothing from the real thing. Somewhere in between is the “contact high.” One student explains this form of secondary intoxication: “You throw all the clothing out of a closet, and you stuff four or five guys inside. You light up some joints, and maybe one or two guys actually smoke. The others just breathe. After a while the whole place becomes thick and oozy. It’s like you’re trapped inside some kind of jar. Everything seems to have walls. You don’t get as much from a contact high as you do from smoking. But it beats just watching everyone else turn on.”

The marijuana user, on almost any given campus, may be placed in one of three categories: a dabbler, a user, a head.

The dabbler has experimented with marijuana, but does not use the drug frequently. For the dabbler, marijuana is something daring — something to tell them about at home. The dabbler refrains from extensive drug usage out of fear, out of moral qualms, or out of immunity to the drug. The large majority of students who try marijuana belong in this category. It is in this group that the “respectable” pot smoker is usually found.

The user indulges on weekends, much the way the rest of the campus uses beer. It is here that the “cult of marijuana” begins. The user enjoys smoking pot, but he also enjoys the mystique surrounding the drug. He is likely to exaggerate the impact of his experience, since he smokes for social as well as psychological reasons. Emotional disturbance is present in such a group, but it does not predominate. What is outstanding is the importance of the group itself. It survives police raids, and even graduation. Often its members dress alike and hold similar political opinions. Drug obsession is rare, and the occasional graduation to stronger psychedelics and amphetamines, or pep pills, is a matter of personal choice rather than group pressures.

The heads, the smallest segment of the drug-taking population, probably make up no more than five percent of all students experimenting with marijuana, but they are often the center of the marijuana cult. The head is high on marijuana most of the time. He often turns on by himself, or with a small group. No matter what the reasons behind his initial experiments with drugs, he now finds an entire personality in this solipsistic world. His most dangerous enemy, as one head says, is any authority, from police to deans and parents; he must learn to live like somebody who is hunted, with the whole respectable world as an enemy. To enhance his stability, the head may often be a supplier. The head may drop out of school, but he continues to make his home on or near the campus. He may eventually become a victim of hard narcotics.

The college student who uses marijuana does not conform to any stereotype, but it is possible to make some rough generalizations about him. He is likely to be either apolitical or liberal; drug experimentation fits into a general pattern of rebellion against society’s values. Marijuana was used in Berkeley’s Free Speech Movement, as it is within many activist groups.

Sexually the marijuana user claims to be experienced. Most students were contemptuous of promiscuous sex, but many reported favorable experiences under marijuana. Doctors are uncertain of the sexual effect of the drug. Though no one has been seduced merely because he or she is under the influence of marijuana, many have found that the drug reduces their fears about sex.

Academically, the marijuana user spans the entire spectrum of grades. The pot smoker may be a dropout or an honor student.

Drug usage also cuts across social classes, but a distinction can be drawn between urban and rural campuses. The use of marijuana is prevalent in the cities. On many Midwestern campuses, it is the cliques from New York and Chicago that first experiment with the drug. On rural campuses, where the student body is composed mainly of local residents, the symbol of rebellion and cool seems to be alcohol, often beer. On Friday afternoon, many Southern campuses undergo what is referred to as TGIF — Thank God It’s Friday. The drinking, to hear students tell it, begins Friday afternoon and ends Sunday evening, around curfew time. In urban colleges, marijuana plays a similar role for students. Marijuana users call beer-guzzling students “hicks” or “foamies.” The beer drinkers call the potheads “junkies” or “fringies.” One Southern student summed up the reaction to marijuana in rural areas: “Man, you could tie me down. You could do anything, but you’d never get me to go near the stuff.” Police officials point to the Northeast megalopolis and the West Coast urban sprawl as the chief areas of marijuana consumption. Except for such areas as New Orleans and parts of Southern Texas, pot is less of a problem in the South. In the Midwest, it is a problem mainly in urban areas, or where urban students gather.

Most authorities admit that there is a danger of permanent impairment after use of the stronger psychedelic drugs. They cite numerous cases of suicide and psychosis brought on by LSD, and the majority of students agree with the authorities. They say, “It’s just not worth the risk.” Many admit they are frightened by such drugs, and most seem aware that “kids who are hung up should stay away from LSD.”

But students are not convinced that there is similar evidence about the dangers of marijuana. One of the major reasons why the marijuana rebellion has sustained itself on campus after campus is the lack of convincing medical evidence against the drug. One student explains, “The only thing that taught us liquor was bad was the hangover. The only thing that made us let up on sex was unwanted pregnancy. But with pot, all they can dig up to make us stop is the narcotics squad.”

Why do so many future businessmen, accountants, teachers and doctors, who differ so markedly in ideas and outlook, share this illegal weed?

A pretty Hunter coed says, “For me, it intensifies everything. Once, under pot, we went into a sleazy little Chinese restaurant … I mean the kind of a place you usually call ‘the Chink’s.’ Suddenly it seemed like the most beautiful place in the world. The wonton soup sparkled.”

A Berkeley student reports, “It broadened the perspective I had on myself. I’m not so fooled by what people around me think. I’ve got a firmer grip. Really, I’m much calmer now.”

From Antioch College: “We all took the stuff and rolled our own cigarettes, and then put on this really cool jazz, and started to smoke. We put blankets on the windows and candles on the floors. The whole room became like the inside of a flame. We were all together in there, and it was like we were doing something wrong that was fun — like eating candy before breakfast — any minute our parents would come barging in to stop us.”

What does pot do?

“It relaxes me. It’s like two drinks without the aftertaste.”

“Nothing. If I’m in a good mood, it makes me feel a little better. If I’m feeling lousy, it makes me feel lousier. So I only use it when I’m feeling good.”

“I imagined I was a lion. I started roaring.”

“I could see inside myself.”

“If we take it before we go to bed together, it makes it all seem better.”

“I saw God inside a flower.”

“It’s like looking inside your own throat.”

“Nothing. Nothing at all.”

“More than anything, I wish they made marijuana-flavored ice cream.”

You climb the stairs in a shabby yet still respectable tenement. You knock on the door, and when it opens you hear the sound of bongos and soft conversation, and you see students lounging in shirtsleeves, in sweaters and skirts. You smell the marijuana — that oozing, languid smell.

The pot party may be anywhere — beneath white porticoes of fraternity houses, or inside tents especially constructed on handy rooftops — but usually it’s at a student’s apartment, away from the campus and prying parental eyes. The apartment itself — no one calls it a pad — is small, but well-kept. There’s a carpet in one of the rooms, and the walls sport cubist prints and Japanese paper lanterns. Scattered around the floor are candles of all shapes and sizes. There is talk of politics and music and much talk of school. The pusher is lounging in a corner with his girl. Everyone sits in small groups. By now, 25 students are present: Talk ceases.

Steve, your host, passes the pot around. He rolls it carefully into cigarettes, using the roller the group chipped in to buy. It is good pure pot bought at a good price and not cut with oregano, which has the same color and texture. Eight cigarettes lie side by side on the floor. You take one up and begin to smoke it, then pass it along.

You hold the smoke in. The windows are closed, and the smoke will soon thicken, making it possible to inhale the atmosphere. You take another drag as the cigarette is passed again. You can feel the preliminary symptom known as the “buzz.”

Soon the butts of cigarettes, or “roaches,” are gathered together and mixed with fresh marijuana to make up a new round. The smoking begins in earnest now, around cupped hands. Nobody wants to let anything escape. You forget the others. You close your eyes for a minute. You are on the beach. There are cigarette butts and seaweed on the floor. You can sense the girls who sit along the rock jetty, waiting for the older boys who have boats to come and pick them up.

Without ever knowing it, you are up. There is no signal, no magic click, just a gradual feeling and a suddenly freer sense of association. Your entire body tingles slightly. There seems to be a constant breeze around you, and it smells unbearably sweet. You are suddenly hungry, and you walk into the kitchen. Now you are slightly nauseated from the motion.

In the kitchen you pick an orange. The color seems gemlike. When you eat, you can feel every muscle in your mouth and throat working; the fruit no longer tastes like any other orange — it has a wholeness of its own.

You return to the room. They are playing the Rolling Stones. The Stones are part of your pot party, because they seem to fit into the room. They sing with their fingers. They seem to be doing exciting things to every song — they are raping the lyrics, word by word. Right now they are singing “Hey, you, get off of my cloud.”

Across the room, the president of a big fraternity, or maybe it’s the editor of the college newspaper, is smoking from your “joint.” Through the smoke you get a feeling of togetherness from that — something like what the radicals must have had in the ’30s. But this seems a lot safer than screaming about class warfare — and a lot less taxing.

You find yourself drinking wine, not because it is intoxicating, but because it is sweet and red, and wine. The label says it is a kosher wine. Suddenly you are an ancient Hebrew, blowing a huge spiral horn while wall after wall comes crashing down upon you. You quote Biblical passages, but later you will not be able to remember them.

All this has taken hours, though it seems like minutes. For a while you go outside. Policemen and ice-cream vendors never suspect you are high, because it is all inside. You can talk when you want to, though the words may become slightly slurred, as though someone else were speaking out of your mouth.

The party lasts well into the next day. Perhaps you fall asleep, perhaps not. Perhaps you return home and awake the next morning to face grumbling parents or house matrons — still slightly high and thus able to take it all.

All you know is that it has been fun, able to be turned on or off at will, and, unlike liquor, without a hangover. And there were no bad experiences — at least, as far as you can remember.

You are still high. You go into the bathroom and brush your teeth. And all the Rolling Stones sway around you — long hair, tight denims, all those hot lights — and you are singing with the microphone between your lips, suddenly happy because you are a Rolling Stone and everyone has finally gotten off of your cloud.

It’s Christmas in Boston.

The Common — a large tree-lined park in the center of the city — is decked with holiday lights. Dioramas depict the Nativity. Sheep and reindeer run loose in spacious pens around the park. Under a bejeweled statue of the Three Kings, five students meet. One is from Princeton, two from Harvard, and the others from Boston and Northeastern universities. Some 20 feet away is a policeman’s shack, disguised as a chapel.

The boy from Princeton is a pusher. He has come to Boston via New York City, where he bought nearly five pounds of marijuana from a part-time student at Columbia University. The others are local dealers who supply friends and acquaintances on their respective campuses. Amid the brassy music of a Salvation Army band and the squeals of delighted children, money and marijuana change hands. No one sees; the cops are drinking coffee. The five students wish each other a Merry Christmas, and separate.

Within three weeks the marijuana purchased that night could appear almost anywhere else in Boston that university students gather.

A few days after the purchase, in a darkened room near Harvard Square, five or six students sit listening to a Bach concerto. The walls are bare, except for a carefully mounted print. The dealer arrives, carrying a green cloth bookbag. Inside the bookbag he carries pot. Two girls produce short-stemmed pipes. The dealer joins the others in an informal circle on the floor.

Some three hours later someone remembers that the dining hall closes in 30 minutes. There is a general scuffle. The windows are opened and magazines are used as fans. The dealer takes the remaining pot and stuffs it into his bookbag. Ten minutes later everyone is eating stew in the dining hall, still high but perfectly respectable. There is a little laughter, someone whispers that the carrots look like pencils, and someone answers that the tomatoes are really bloody eggs. At the next table other students are giggling over the new Fellini film. After dinner everyone will study.

This is one Harvard party. There are also the big Harvard pot parties, almost always with girls present, and usually held in private apartments in the slum sections of Cambridge. The drug scene at Harvard is normally played in private. The pushers, or dealers, are often students themselves. They make connections in Harvard Square.

At Harvard Square, pot is slightly more expensive than in Times Square ($5 will net twelve cigarettes in Boston, fourteen in New York). Stronger psychedelics, on the other hand, are cheap in Boston. The price of LSD has dropped from $5 per dose to 75 cents. The reason, police claim, is the increase in supply around campuses.

Public concern over marijuana at Harvard can be traced to an article that appeared in The New York Times last year. In that article, Harvard students estimated that from one fifth to one half of the students at Harvard will have tried marijuana sometime during their stay at Cambridge. The article unleashed a storm of criticism from Boston judicial authorities and from Harvard administrators. A Harvard College dean told one reporter that “adult estimates of marijuana usage here run about one percent.”

A more recent estimate, from a Harvard Crimson reporter, runs close to 30 percent. Last December, Harvard placed four students on probation for the use of marijuana. Other students reportedly have been placed on probation after unpublicized discoveries of drugs.

There are nine Residential Houses at Harvard, and the Residential House, with its own dining room and library and tutoring staff, is the basic social unit. It is normally within this unit — and not on the streets of Cambridge, as police claim — that the students engage in drug experimentation.

Most houses attain status-images. As a result, the “preppie” type is likely to live in either Eliot or Lowell House. The athletic student can usually be found at Winthrop House. And the Bohemian element prefers Kirkland or Adams House. One ex-student of the college explains their social habits this way: “Walk into Winthrop House, and they’ll offer you a beer. Walk into Lowell House and they’ll serve you an aperitif. Walk into some of the other houses, and you might get a marijuana joint.”

Few smokers are ever expelled — if they agree to spend some time with a psychiatric worker at the University Health Service. A student at the college says, “It’s generally known that if you have a drug problem you can go to the Health Service and they will keep it confidential.” Dana L. Farnsworth, director of Health Services, says, “The Health Service is anxious to help students find medical solutions to the drug problem before they are implicated to the point of being subject to legal action. … The best thing we can do to protect the student is to help him protect himself.”

There are some 30 schools of higher education in Boston, and this does not include Cambridge, or any of the numerous Boston suburbs. Life for a Back Bay cop is sometimes like that of a private campus guard. “We’re like a campus police station,” a narcotics agent says. “This is all a new field for us. We have to do work in dormitories, and rooming houses, and anywhere that college students gather.” He calls marijuana in schools such as Boston University “a problem that has been mushrooming.” “Last year we took in isolated cigarettes,” the agent declares. “This year it’s in five-dollar bags, in ounces, even in pounds. Last week we hit an all-time high — sixty pounds in one seizure.” He removes a key from his pocket and opens two long footlockers, exposing tightly packed marijuana. “That came from Mexico, through California and New York, and here it is in Boston. But we lose most cases we bring into court, because of the type of defendant — the caliber of the people involved.”

Two fine-arts students at Boston University demonstrate “the caliber of the people involved.” They are serious students. “We get our pot from friends, mostly,” one of them says. “Someone will buy in bulk because it’s cheaper that way. He sells what he can’t use. So, we get his name and maybe call him up. There just is no underworld involved at B.U.” Another student admits that he grows marijuana in his parents’ home, “in the backyard,” and harvests a crop during every holiday. “My folks think it’s philodendron,” he says.

Police officials believe that drug usage at Boston University and other schools in the area is an off-shoot of Ivy-university experimentation. One college official commented, “Apparently my students began to smell the odor wafting across the Charles River. I think they get high on romantic notions more than they do on narcotics. I think the Harvard men made it seem like the thing to do, and police raids made it seem like the thing forbidden to do. Everybody just jumped on the bandwagon.”

Why do the students use marijuana? The pressures at Harvard are mentioned. “Pot takes the pressure off in a very real way,” says one honor student. “There’s a sense of total, timeless ease.”

The impersonality in a large university is blamed. “When you smoke,” says one student, “it’s like a big conspiracy. It’s personal; there’s a common enemy for the whole group.”

A long-time administrator asserts: “Kids are rebelling against adult norms. They think they are more rational and realistic than their parents, and smoking marijuana is a way to prove it.”

“I’d be lying if I didn’t mention the social factor,” says a Harvard student. “Pot gave me a real sense of purpose, an assurance, a kind of concept of the straight and narrow, though that might sound ironic. The whole thing is the kids you smoke it with. You really start to share bits of yourself with the smoke. And after a while you’ve got friends, and an ideology, and even girls — you’d be amazed at how many Cliffies [Radcliffe girls] equate pot with seduction.

“Even after the pot is over, I mean even after you graduate and begin your career, and, you know, begin wearing bowlers and vests, the group still holds together. I predict that when we’re all thirty, we’ll be shocked by whatever is the pot of the new generation. But we’ll still be together.”

On most campuses, there is a rigid line between pot and more dangerous psychedelic drugs, such as LSD. At Harvard the line is much less firm.

Such drugs were recently available under the aegis of Richard Alpert and Timothy Leary, two professors of psychology at Harvard. Their experiments with the consciousness-expanding properties of LSD and psilocybin (another hallucinogen) brought the university its first major scandal over drugs. Before their experiments were discontinued, 167 persons, many of them Harvard men, had tried such drugs. Leary ecstatically noted that 95 percent of the students reported positive, meaningful experiences under psychedelics. But for the other five percent the psychedelics were a living hell. Two students wound up in mental hospitals after taking the drug. A third was almost killed when he walked into oncoming traffic, convinced that he was God and could not be hurt.

In 1962, the university gave undergraduates a formal warning about dangers in the use of hallucinogenic drugs; in 1963 the university fired both professors. Since then, the two men have become martyr-heroes to the psychedelic cult at Harvard. Harvard men, curious over reports of “mystic insight” and anxious to take part in this new and meaningful ritual, began to investigate sources for the drug outside the university. They found them soon enough.

One student who has used psychedelics while at Harvard admitted that “students aren’t sufficiently aware of the dangers around psychedelics. I know one hundred people at Harvard who have used psychedelics. One cracked up completely. And one in five have had bad highs.”

Psychedelics are not as widely used at the colleges which surround Harvard. At Boston University they are “rare and very personal.” At Northeastern they are “talked about but never seen, like flying saucers.”

But Harvard is not the only Ivy League college campus at which drugs are plentiful, forbidden, and mysterious. If Yale University in New Haven, Conn., has not yet suffered a major drug scandal, it is not because the student body has shunned pot. “Pot is fairly common here,” says one student, “but no one seems to be able to put his finger on it. It’s very private here, and smoked in very small groups.” Another Yalie declares: “Everything went underground after the Harvard scandal. Everybody here has a career to think about, and a future. No one is willing to risk it all for the sake of one tiny forbidden thrill. But marijuana does exist here. The hip people are hip, but they are being very quiet about it.”

The use of marijuana at the “seven sisters” women’s colleges seems related to contacts within the Ivy universities. Smith, Radcliffe and Barnard girls are common appendages at pot parties at Yale, Harvard and Columbia. They are not stunned onlookers, but delighted participants.

But women students seldom turn on with members of their own sex. One student at Smith College explains, “Somehow, pot is a masculine business. It’s groovy enough to brag about going with a pothead, and of course it’s fine to imply that you’re joining him — in everything. But you don’t smoke the stuff with your friends, or in your dorm. It just doesn’t mix.”

And a Cliffie sums it up, “We go across the street to pot parties. Sometimes we come to my room, but we’re always with a crowd of guys and girls. Women just don’t smoke by themselves. It’s unladylike.”

New York City is America’s largest college town. Its student population of 250,000 could fill many American cities. Its Student Union is one of the world’s great Bohemian quarters — Greenwich Village. And, since the great majority of students in New York are native New Yorkers, their manners and mores differ sharply from what has come to be called “collegiate.” Campus dances are well attended, but the endless row of foreign movie houses on the East Side, folk clubs in the Village, and theaters provide an inexhaustible supply of off-campus entertainment. The average New York student lives either at home or in an apartment surrounded by non-students. His parents are not voices on the long-distance telephone, but, usually, a physical presence. If he wears a beard, or shoulder-length hair, he must do so in the middle of a well-scrubbed Brooklyn or Bronx neighborhood, which is no easy task.

There is a simple explanation for the prevalence of marijuana on New York City campuses. Police officials admit that the fascination with that particular kind of “high” is an urban phenomenon, and New York City, as one of the world’s greatest urban conglomerations, is the natural place to find the most marijuana at the cheapest price. But the Federal Narcotics Bureau denies that the “mob” is involved in marijuana traffic, since the profits are paltry compared with those culled from illicit heroin traffic.

Drugs are present on all of New York’s campuses, but there are some colleges at which drug experimentation is rare, and almost never public. This is especially true of the Catholic universities. A student at Saint John’s University says, “Maybe there is drug experimentation here, but it’s completely underground. You expect that on a campus of this nature, where protest and rebellion just aren’t part of the scene, the way grades and dating are.” And on Fordham University’s Bronx campus, a senior says, “It’s all beer here. In many ways, Fordham is like a respectable Southern school. It’s not that the students are overly pious; they just have a well-developed sense of propriety. Besides, everyone knows that in the Bronx, the Irish drink beer, the Italians sniff glue, and the Jews smoke pot. And this is an Irish school!” Explanations of sociological phenomena based on ethnic considerations are always suspect, but it is a fact that marijuana is a problem on many city campuses where Jews form at least a sizable minority. Many sociologists have estimated that Jews are unlikely to join the nation’s growing ranks of alcoholics. They point to a long-standing tradition in Jewish culture which treats the consumption of alcohol as a commonplace occurrence. For the Catholic student in New York, rebellion often takes the form of frequent alcoholic bouts. But for the young Jewish rebel, marijuana, non-addictive, but thoroughly unrespectable, could be a better vehicle for parental defiance.

For those who want it, pot is easily obtained at New York University, the city’s largest private educational complex, which enrolls 40,000 students. The university’s major campus is located in a center of the city’s drug traffic — Greenwich Village. Last January, NYU expelled an undisclosed number of students from a red-brick dormitory on the Washington Square campus, apparently for suspected marijuana smoking. The administration has steadfastly refused to discuss the case in public, but students were outraged at the action. They accused the dean’s office of spying, conducting an inquisition, and bowing to outside pressure. The city’s press, in turn, was shocked at what appeared to be the widespread acceptance of marijuana by students.

Isidor Chien, professor of psychology, offered an explanation. He said, “Adolescence … is a period in which the problem of identity is most intense. If past experience is any guide, the greatest bulk of even the most radical experimenters — if not punished — will grow up to be staid, respectable, middle-class citizens complaining about their own children.”

Roger, an NYU sophomore, tells about the availability of marijuana on his campus: “Anyone who lives near New York and comes to the Washington Square campus to study knows that sooner or later he’s going to be offered pot. It’s so absolutely easy to find. It floats around. It’s possible just to go to pot parties with friends and stay high weekend after weekend without ever spending a cent. I mean our student union is Macdougal Street in the Village. Look out any classroom window any time, and if you’re sharp enough, you can witness drugs changing hands.”

Hunter College, in the Bronx, is part of The City University of New York (CUNY), a conglomeration of 11 colleges including Queens, Brooklyn, and City College. The city transit system is all that unifies the student body of the City University. Since students go home every night, there is little pressure to become standard collegiate, and the college is not responsible for the lives of its students after 3 P.M.

No one knows who started it, or how it spread, but somehow pot became cool at Hunter. Even smokers denied this at first. Then last year Meridian, the student newspaper, decided to survey the campus on the use of drugs, because, as a reporter in charge of the survey said, “We knew that it would make news.”

It did, although the results were so staggering that they were never printed in their original form. On a campus of 4,000 day students (those who go to school full time), 400 or 500 students had smoked marijuana more than twice and considered themselves users, the Meridian found. But it was not the statistics that surprised the Meridian editors. It was the discovery that the fraternity man — long the stereotype of respectability, the one who was headed for conventional success in the suburbs — smoked pot. Meridian found that the average user was beardless, dungareeless, and guitarless. He was a respectable student, without emotional problems or disturbing qualms about where he was going. He used pot “because it’s fun,” and “because everyone does.” Furthermore, Meridian found that marijuana was present within the student government.

“Once we knew it was safe, we figured it was cool,” one fraternity brother explained. “You were on the fringes of being a degenerate when you used pot. But you were still safe.”

The Meridian report was presented to the school administration. The reactions ranged from skepticism to gratitude, but some two weeks after the presentation, panic set in. The word went out that the dean had a list of all marijuana users on campus, the FBI was present in droves, and there was going to be trouble.

Some three hours after the rumor hit the student cafeteria, the waiting room of the dean of students began to fill with worried students. They were assured that there was no FBI and there were to be no recriminations for past off-campus activity — but the dean’s office had been given concrete proof of pot at Hunter.

Eventually, however, police entered the scene. Five Hunter students were arrested. Found in the apartments of two of the students were no less than seven pounds of marijuana, a half-ounce of cocaine and a small quantity of LSD.

Students, stunned by the arrests, realized something that they had conveniently forgotten back when marijuana was an adventure: Whatever its attractions, pot is illegal. Suddenly friends were behind bars, and news reporters were scattered around the campus. Suddenly parents were grumbling about “that Commie school,” and asking their children, “The truth or no allowance — are you a junkie?”

“The bust was the only thing that made us feel using pot was wrong,” one Hunter student says. “We finally realized we were doing something illegal. Before that, so many kids were doing it so openly, you never thought the cops would dare bust us. So, we all stopped using it for a while, at least until things blew over.”

Things have since quieted down at Hunter College. But marijuana is still there. Everyone knows about it, though no one says very much. Once in a while the school newspaper has printed sly references to confirm the fact in code — “Hunter Grass Festival Next Week,” or “Be Ahead — Join Meridian.”

The City University’s largest college is the City College of New York, CCNY, and, according to a CCNY official, drugs are not a problem.

Jim agrees that pot is not a problem at City — at least from his point of view. As a campus pusher, he is ecstatic about the whole thing. After pushing marijuana for just four months, he temporarily retired — $2,000 in the black. At 50 cents a cigarette — the going New York price — that’s quite a lot of marijuana.

Ray, a City College junior, is a good friend of Jim’s and a good customer. He says, “The campus is a good place to smoke. You meet your friends there; it’s congenial. It’s a social gathering place.”

He takes you around the campus, to the places where “the scene” happens. There are secluded sections of cafeterias, chipped-plaster tunnels, rooftops, and lawns. On the South Lawn you watch a dozen students smoking in a small circle. Their books are open and one strums a guitar. It is only as you get closer that you realize they are smoking marijuana.

“Many smokers like to turn on around the South Lawn,” Ray says. “It’s pleasant in the spring.”

Just what is the extent of marijuana usage at CCNY? Jim begins figuring in a CCNY notebook.

“Including fraternities … and hippies, 20 percent. Almost no one ever gets to heroin or anything like that.

“That’s this year. It’s all starting to change, you know.” Jim looks up from his book and smiles. “There’s such a difference in the attitude. That’s what’s so amazing. A while ago everyone was shocked when you mentioned marijuana. Now everyone knows about it, and even kids who never use it talk about it — a lot. Sometimes they even pretend to be high. But you can always tell. They’re not really happy.”

A few blocks away, in the Morningside Heights area of Manhattan, Dean David B. Truman recently told the undergraduate newspaper, The Columbia Daily Spectator, that he would be surprised “but not totally astonished.” to find out that one third of the campus had smoked marijuana.

Truman’s statement followed the apparent suicide of a “model” student, Tim Rolfe. When police found Rolfe’s body in his dormitory room, they uncovered a cache of narcotics — including marijuana — and a diary containing names of students. One reporter on the Spectator describes what happened as the suspicion spread that Rolfe was a drug pusher. “Well, there was quite a panic here. Everyone knew that the dean and the police had the diary. But the students mentioned in it were never caught. Some came voluntarily, both to admit they had used pot and to insist that Rolfe was not a pusher.”

It is difficult to determine exactly what the administrative attitude toward the use of drugs is at Columbia. One administrator made a stab at it when he said, “We treat drug users as individual cases, and not by any hard-and-fast rule.” The rule — if there is one — seems to be: If the student is pushing, he is suspended; if the student is experimenting, he is referred to psychological counseling.

Anthony F. Philip, chief psychiatrist for the student health service, admits, however, that the use of drugs may not indicate a severe emotional problem. “There’s nothing potentially dangerous in essentially healthy students trying marijuana,” he said. “It’s part of the maturing process, trying new experiences. But for some students, for those who lack commitment to any set of goals or feel lost in a very profound way, it can be quite bad.”

At Columbia, marijuana is sometimes given as a Christmas present (one pusher revealed that he specially packages $2.50 doses of marijuana — which he calls a “thrupence bag” — for purchase by Columbia students around Christmas time).

And pot is smoked with a special swagger among fraternity men. A reporter on the Spectator claims that “marijuana is used extensively in more than one of Columbia’s fourteen fraternities. And when I say extensively, I mean they hold secret parties for that special purpose.”

A member of one such fraternity described a pot party here as “more of a primitive rite than a wild party. It’s all very organized, and secret. You have a special knock. You can’t bring guests, and girls just aren’t allowed. Everyone sits around and passes pot. It’s done very slowly, and there are records going.

“Then, after a while, it becomes wild. There’s this weird sense of competition about the whole thing. Everyone has got to get a better, more unusual high than the guy next to him. It’s all really kind of a farce. Sometimes I watch these kids faking and bragging, and it just makes me want to crack up. All those faces they make — it’s phony. But I do it anyway. I mean, after all, these guys are my friends.”

Huge marijuana raids are not infrequent in the area around Columbia, and the school is some 20 blocks away from the most notoriously addict-filled area in the city, a stretch of Broadway that culminates in a small plaza known locally as “needle park.” “With all the dope around here,” a policeman says, “it’s a miracle these students never run into any of the hard stuff. You hardly ever get students in a real dope raid. Only on the petty stuff, like marijuana.”

Rod, a 19-year-old junior at Columbia, has been a campus pusher for “a few years.” Tonight he stands along tree-lined College Walk, beneath a statue of Alma Mater — a stern, seated lady.

He is easy enough to reach. You get his first name from a student customer. You call him up. You make an appointment. He makes “a few thousand each year.” He sells “marijuana, LSD, pep pills, and a small amount of heroin. There’s not much demand for pills around here, except around exam time.”

Rod is a rarity — he is a college student and a heroin user at the same time. No one would suspect what his “hobby” is, from looking at, him. He has no beard, he wears no political buttons, he carries his draft card safely on his person. He obeys all laws and all social customs. He dresses well, talks well, and “makes out OK.” He pushes “to earn a little extra money.”

Unlike the campus pusher who buys marijuana for a small group of friends, Rod guarantees nothing to his customers, and he admits that those who buy from him receive marijuana that has been heavily cut with oregano.

“In this business, nobody asks you questions. This is a free-enterprise system around here. It’s not my business what happens to my customers, or what kind of a high they get.”

But Rod leans against the statue of Alma Mater, his finger tapping against her bronze toe.

“It’s like the Romans said: ‘Let the buyer beware.’”

In the college drug world, the New York City student plays another key role — that of migrant supplier of drugs. Every year thousands of New Yorkers leave their native city to study at suburban or Midwestern schools. Though they disperse themselves among the student populations, they tend to congregate at certain schools where they know they will find others of their backgrounds. Cornell University, in upstate New York, is one such institution. Berkeley is a West Coast haven for New York students with a wanderlust. Antioch College in Ohio, Bard College in the Hudson River Valley, the University of Miami, nestling among the palm trees in Vacationland — these are other places where New Yorkers gather.

Sometimes, as in the case of the University of Miami, they arrive expecting lush tropical vegetation and academic recreation. Sometimes, as at Berkeley, they search for a place where any idea or way of life will find acceptance. They enter Antioch or Bard because these are small “progressive” schools with a sense of student identity which they find missing in the big-city multiversities.

Wherever New York students go, they bring their culture with them, often including pot. They soon find a hangout; they congregate in private apartments. As their number grows, the word spreads — pot is fun, safe, and ever so illegal. In due time, the police get involved.

Bearded agents recently posed as students and made two purchases of marijuana (at a cost of $435 for three pounds) in Philadelphia. They trailed the dealers back to Rutgers University’s South Jersey campus and arrested seven students in an apartment near the university in North Camden, N.J. These seven were charged and arraigned on various counts, ranging from possession to sale of marijuana. At 3,000 cigarettes per pound of marijuana, the police had bought enough for close to 9,000 cigarettes — all destined to be smoked by students. The New York State Narcotics Bureau has evidence of marijuana consumption on at least 15 upstate campuses.

Or, take Miami U. A pleasant university — palm trees, beaches, air-conditioned classrooms. One student at Miami recently said, “I wouldn’t say pot is in much demand with the Southern crowd out here, ’cause they’ve got other ways of telling who’s with it and who isn’t. It’s with the kids from the cities, especially New York, that you get pot parties. It’s all very outdoorsy. There’s a lot of fuss made about going outside and running along the streets high. I think the idea is to confront all the straight people.”

At Miami, as at most schools throughout the country, the “straight” people seldom strike back for fear of publicity. They remember what happened at Cornell. That upstate New York university has been plagued with scandal after scandal over marijuana.

Cornell University borders on the small city of Ithaca. Its 13,000 students make up nearly one third of Ithaca’s population. Those students who do not live in campus dormitories take apartments in “Collegetown,” a small section of stores and student services adjacent to the campus. For those who cannot afford to live in town and who cannot find a place in Cornell’s dormitories, joining a fraternity is the most convenient way to live.

Cornell has its New York hippies. They wear the same boots and English-style hairdos as on other campuses, but somehow in the horse-and-buggy atmosphere of Ithaca they seem more extreme, more rebellious, more hip. Other students stare at them. In their Collegetown hangouts they talk and laugh at their own jokes. There is a notable sense of the exclusive about everything they do. The hippies do not speak for Cornell. Marijuana is less commonly used than at either Harvard or Berkeley. Yet if any one campus has achieved a notoriety for drug usage, it is Cornell. The first pot raid involving the Cornell campus occurred in the spring of 1963. This was swiftly followed by another raid in the fall of 1963, the same day President James A. Perkins took office, and still another in the winter of 1965.

The 1965 raid is typical both of Ithaca police methods and of the curious ring that operates from campus to campus around the East. During the 1964 Christmas recess a 21-year-old Cornell student mailed a “nickel bag” ($5 worth) of marijuana to a student at Connecticut College; the recipient eagerly opened the package and lit up. She became ill and went to the infirmary. Word got around. Connecticut College President Charles E. Shain notified Cornell, and Tompkins County District Attorney Richard B. Thaler began an immediate investigation.

Rumors spread across the Cornell campus that another marijuana raid was imminent. The hippies panicked. At a meeting of the student government, a member claimed that a pot investigation involving over 80 students was under way. The Cornell Daily Sun, the student newspaper, got hold of the rumor, and the administration finally released a statement:

Cornell University views with utmost concern the availability of marijuana in our community, and its use by even a few students. When the university learned of the present case, it reported the matter to the District Attorney’s office. Cornell hopes the investigation will lead to the real offenders in this vicious business — the organized network of producers and agents who prey upon young people and persuade them to experiment with habit-forming narcotics.

The Daily Sun revealed that University Proctor Lowell George questioned 25 students, but the results of the investigation were inconclusive. The Cornell girl was charged with the sale of narcotics. So was the boy she bought the nickel bag from, a former Cornell student and the son of a professor. District Attorney Thaler blames the make-shift results of his investigation on the Daily Sun. “The paper left us hanging in mid-air. It completely broke the secrecy of our investigation, and we found it much more difficult to proceed. Everything went underground.

“This a fad,” Thaler says. “The kids think this is a sophisticated way of feeling they can handle anything. It’s kind of a superman thing. But what happens, after a while, is that the kids lose track of the legal restrictions.” He asks for special legislation to deal with marijuana experimentation. “These kids are different from slum users,” Thaler admits. “There should be a way to bring across the point that marijuana is wrong and harmful without incarcerating them for five years.” Thaler points to the difficulties in enforcing the law. “The court is very unlikely to convict an above-average student — which is what most of these people are — for puffing a marijuana cigarette. You have to get them pushing, or else it’s hard to do anything except get them kicked out of school.”

How effective has Thaler’s campaign against marijuana at Cornell been? The police call drugs “a continuing problem.” The administration says it is keeping the situation under close surveillance. But Judy, a long-haired coed at Cornell, finds marijuana “just as plentiful, and even more popular here than it was, say, two years ago.” She estimates that “up to 15 percent” of the campus has used marijuana, and she says that this figure represents a noticeable increase. “Because it seems to be more forbidden here than anywhere else, kids use pot with more of a relish. I mean, there really is a danger involved in smoking it, so it’s not just a safe rebellion.”

Marijuana flourishes on campuses like Judy’s, where a small group of urban students band together to shelter themselves from dominant campus mores, which conflict with their own. When this happens at a small Midwestern college, the few Easterners who experiment with drugs can be conveniently dismissed as “kooks,” “beatniks,” or “rebels.” By the time police and administrators take note of the scene, the urban student has accomplished what he has set out to do: He has carved out a place for himself and his peers in the university structure. And he has given the school a reputation so that others of his persuasion will want to follow.

There are a few schools in which such transplanted students make up virtually the entire student body. Perhaps the best known of such “transplanted schools” is Antioch College, located in Yellow Springs, Ohio. Antioch offers a curriculum and a disciplinary system unusual among American colleges. For 1800 Antiochans, college is a five-year adventure. Ten quarters are spent at work, on jobs located all over the country. The “work break” provides Antiochans with a wider range of experience than the average college student could ever hope to encounter.

But academic scheduling is only part of what makes the Antioch experience unique. In areas of personal and group morality, the college operates on a strict honor system. The college community votes on its voluntary curfew for visiting within the dorms, and once that curfew is established there is no one present to force students to abide by it. Tests are often given out of class, and the student is expected to take them on his own time, and on his own honor. On the whole, the honor system works.

But the honor system has not been able to cope with the use of marijuana by Antioch students.

Estimates of just how many Antiochans try marijuana during their college “adventure” vary, but many students questioned indicated that the figure is unusually high. There are many reasons why marijuana experimentation might be common at Antioch. The college is a closed, sheltered community. There are few student hangouts in the town of Yellow Springs, and few occasions when the students mingle with townspeople. There is resentment against Antiochans among residents of Yellow Springs. But, as one Antiochan says, “When you’re subject to criticism and slander from the outside world, you emerge with a tremendous sense of solidarity. We tend to take care of each other.”

Antioch’s dean of students, J. D. Dawson, recently told an assembly of students, “There are rumors and misunderstandings floating around, and much concern about the college’s position on drug usage. In acting on an educational basis rather than on a punitive one, we have been wrongly interpreted by some as condoning the use of drugs.” The dean warned the students of “the physical and psychological dangers” and “serious legal consequences” of illicit drug usage. “Students engaging in this type of secret practice sabotage the honor system and the open community.”

Yet, despite the warnings, many students insist that the right to quiet, private experimentation with drugs is inherent in the notion of the open Antioch community. “It’s not a frenzied scene out here,” one student notes. “Nobody uses drugs out in the open, and no one flaunts it around for cool. That’s because it’s so easy to get here, and such a peripheral part of things. It’s available to almost everyone.”

At Shimer college, a small “progressive” Midwestern school in Mount Carroll, Ill., malicious mind-busting is the only cardinal social sin.

Mind-busting is taking advantage of a student who is high on pot — and thus susceptible to suggestion.

For instance, “You tell someone who’s inhaled pot for a while that he’s been holding his breath for twenty minutes, and he’s liable to believe you. It really busts his mind.”

Or, “You keep shouting at some head, ‘What’s the matter with your face, huh? Hey, look at it, it looks ugly. You’ve got two noses.’ And you keep shouting that kind of thing over and over again.”

Or, “You start creating a tunnel around the guy’s head with your hands. You start chanting at him, ‘I’m drawing your mind out of your head, it’s coming out through your eyeballs, it’s coming into my hands.’ And then, after ten minutes of this, you suddenly clap your hands hard together. It blows the other guy completely.”

Shimer students draw the line between “malicious” mind-busting, which results in terror for the victim, and “ego games,” which add pleasure to the marijuana high. In an ego game, for instance, you wear a pair of glasses with lenses tinted in complementary colors. Or “You let your friend look at the steel tip of an umbrella for ten minutes. Have him really concentrate on it until he can see it change colors. Then suddenly you open the umbrella in his face.”

The effect is not as bad as it might seem. “The guy usually starts laughing — it’s so unexpected. It’s like seeing a magician pull a hat out of a rabbit.”

All this is one small aspect of the marijuana mystique at Shimer College, and Shimer itself is one small part of the marijuana mystique among students throughout the Midwest. But the college, nestled among the quaint brick streets and small farmhouses of Mount Carroll, is the Midwest in miniature.

The town of 2,200 is dominated by the college. And Shimer itself is an academic small town, with a small, well-integrated student body. Its curfews are standard (midnight for girls, none for boys), and its regulations are respectably strict.

Shimer students are an isolated, self-contained community with their own language. At Shimer, a “frat-rat” is “a guy who’s flunked out of another college and comes to Shimer with all the trappings of a fraternity type.” A “teenie-bopper” is “a guy who is completely stuck on rock ‘n’ roll, thick sweaters, and convertibles,” “the center people” are those in student government, and “the folk” are the hipsters and the Bohemians.

The obsession for labels extends to the marijuana cult. “Scissors” is code for marijuana. “Can I borrow your scissors?” means “I want to buy any pot you can sell me.” “I need a haircut” means “I want to turn on with you.” The folk turn on. The center people may be involved, but they are mellow — respectable. The athletes turn on, but not publicly. The teenie-boppers are sometimes hippies, and their pot cult is loud, ostentatious.

And when the Shimer College student smokes marijuana he partakes of two aspects of the pot scene that are especially apparent in the rural Midwest: secrecy and ritual.

During semester break, eight Shimer students fill individual pipes from a plentiful supply of marijuana which lies in the center of the floor, and they inhale deeply. The tiny, short-stemmed instruments are called Toke pipes. They are purchased in Chicago from a girl in Chinatown who provides the best in opium and marijuana smoking equipment. The pipes are shortened, and the holes in the bowls narrowed so that only a thin stream of smoke passes through to the user’s lips.

At Shimer, the Toke pipe is a prime object of the pot mystique. It is decorated in bizarre patterns, with silk thread, feathers, dyes and colored glass. It is carried in special pouches.

And, to complete the ritual, the students produce a large, multicolored candle, with complex geometric patterns carved into the melting wax. “We never turn on without it,” one of them explains.

Where does he get his pot? A prime source is Chicago. One Shimer student claims, “Shimer and the U. of C. [University of Chicago] have a game going. There’s no real pushing involved. Everyone just chips in five dollars, and we send someone down to Chicago to bring some up.” Students claim there has been some police investigation of this supply route (cars and rooms of visiting Chicagoans have supposedly been searched), without much success.

There is also Berkeley and New York. “Kids just kind of float through here, and in a week they can push up to a kilo [2.2 pounds] to other students.”

But the major sources of marijuana for Midwest students are the surrounding corn fields. Marijuana grows wild in Illinois, as it does all over the country, and students were quick to take advantage of this natural bonanza. One student says, “We picked three sports car loads of pot in forty-five minutes, right outside of town. We stripped the leaves behind a barn, and then we put them into laundry bags. We drove to school and threw everything in the dryers in a campus dormitory till the humidity was removed.”

The student dealer who tells that story reveals that seven friends subsequently turned a dormitory room into a marijuana drying house. “We put a cover of muslin on the floor, then a layer of pot, then some more muslin, and some pot, and finally we strung heating lamps from the ceiling.

“When it was all over, we filled a whole footlocker with good, smokable pot. It was worth over ten thousand dollars. I bought two motorcycles from the profits.”

There is as much marijuana in Chicago as you would expect within a metropolitan area of six million people. There is also supposed to be “the syndicate” — a mysterious, vague source which reaches even into the student pocket for its revenue. (No one speaks about the syndicate on campus, but everyone assumes that it controls marijuana traffic within the city.) In addition, there are the campus dealers who carry their wares in the trunks of convertibles and in motorcycle toolkits, and supply students in nearby universities — like Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Antioch, and Shimer.

In Chicago’s Hyde Park section, on the south side, the scene is played in the small nonalcoholic restaurants where the university meets the ghetto. Both Hyde Park High School pupils and students from the University of Chicago, which is located in the Hyde Park section, meet in these coffee and pop bars. Dealer meets customer at these same coffee bars, but the actual exchange of drugs rarely takes place in public.

In Hyde Park, pot is smoked in the small student apartments within this university “town.” In one such apartment, a fifth-floor walk-up with a view of the Illinois Central Railroad tracks, Joseph Peters [pseudonym] sits among his record albums, his books and his Beatle posters, and talks about the scene at the U. of C.

“Being under twenty-one and living here,” he says, “it’s easier to buy a nickel bag than a pint of gin. And Hyde Park is not such a bad place to make a connection. The FBI is around — everyone knows it, and everyone knows how to spot a narco [a federal agent], so the whole scene is pretty secretive. Small parties, that kind of thing. But no one congregates around here. You don’t go around Hyde Park asking questions.”

Joseph estimates that 10 to 15 percent of the University of Chicago is involved in marijuana consumption, though he admits that estimates are hard to make.

“Many people have the image that the U. of C. is the homeland of the Midwestern radical,” he says. “This isn’t usually true. Most of the kids are straight — at least when they come in.”

What makes some of them potheads by the time they leave the university? Bill Jackson [pseudonym], Joseph’s roommate, says, “First of all, almost everyone at the U. of C. accepts pot. About eighty percent of the kids know what it’s all about. The only thing they don’t know is where to get it, and if they did, a lot more would be using the stuff.”

“The idea is to stay cool, not hooked.”

A Chicago pusher may be a student, a townie, a dropout, or a supplier with shadowy mobster connections. One pusher, a University of Chicago student, says he deals only with friends. “I didn’t come into this crowd as a pusher,” he claims. “I had money to begin with — my folks are pretty well fixed.

“Frankly, I started because it seemed like a good way to make friends. It was like a treasure I was giving out when I began to deal in pot.”

Bill Jackson calls this pusher “emotionally screwed up, but harmless. He goes into laughing fits whenever he’s high, even on beer. He talks to paintings, starts necking with trees, you know, like that.” But Bill Jackson will remain friendly with his pusher because “basically I know his limits, and heroin is beyond them.”

Another pusher, a townie who dropped out of high school and began using marijuana at 13, was “always on the periphery of the circle,” according to Bill. “But when we found out that he was using H [heroin], he was dropped completely. There was this stigma about using hard stuff, and it just went into action as soon as it became apparent he was hooked. I think we were all a little surprised at ourselves for being so intolerant. After a while we’d never mention him. He just floated away and into another group.”

The University of Chicago administration knows little about the world of the campus pusher. George Playe, dean of undergraduate students, admits that “no administrator anywhere is fully aware of what the drug situation is like on his campus.”

But Dean Playe insists that “a very insignificant proportion of the student body, perhaps only five percent,” uses marijuana. He characterized such students as “rebellious, uncomfortable in social situations, and marginal — academically.”

Dean Playe terms the cooperation between police and university officials “reluctant.” “We try to make a distinction between the user and the pusher here,” he says, “but when the police are involved it’s out of our hands. I certainly don’t know of any university that can take the stand that punitive means of dealing with this kind of problem are to be desired.”

But Dean Playe admits that “the fear of retribution is the primary reason for the lack of wide-spread marijuana experimentation at the University of Chicago.” If the legal barriers were removed, it seems likely that drug usage would soar. “The people from both coasts are likely to be the sharpest in locating the supply,” Dean Playe declares. “And there’s always the kid from New York who comes up with his own suitcase full of pot.”

Mike, a student on the University of Illinois campus in nearby Urbana, speaks while high on pot and beer. “The new thing is digitalis [a drug used to prevent heart failure among victims of angina pectoris]. It takes you up and brings you down again like a rocket. It makes pot feel like cotton candy. The real hippies — I mean the ones that matter under the purple sunglasses — go in for the stronger stuff. Under pot, Urbana is a swinging place to be in. Under psychedelics, Urbana no longer even exists.”

Mike lives in Chicago, and he is glad to be home again, even if only for vacation. After it’s over, he will return to the University of Illinois laden with a fresh supply of marijuana — “Acapulco gold, the best stuff,” he claims. But now Mike relaxes in the house of a friend, listening to a folk-rock record, and chatting.

“I like to turn on along the lakefront when the weather gets warm,” he says. “It’s long and spacious, and very blue. It smells blue under pot. And you forget about the whole city. It’s like a little strip of space in which to have your own high-on-pot-type thoughts. It’s very central to my pot experience. I like to be alone, and outside, and — you know — feel free.”

Part 2

“Paranoia is a hipster’s disease,” says Ray, as he fingers his wool-knit tie at a table in the University of Wisconsin Student Union. “Everyone is constantly scared of being busted. Ostensibly it’s kept very quiet, but the very fact that I’m sitting in the Union here and talking to you about it shows how careless everyone is. You could be an agent. It’s happened before. There are constantly rumors of imminent busts. People always suspect that there are informers around. And they have good reason to. It’s damned easy to hate the police out here. If you’re a hippie, you’re considered part of the underworld. You’re treated like a real junkie.”

Paranoia is a common word among Midwestern college students who use marijuana. Ask a student to tell you where he gets his pot and he blanches and tells you to speak more softly. It’s around, of course. “Wisconsin is a big stopping-off place for kids traveling from the East to the West, maybe from Harvard to Berkeley.” But the student adds in a whisper, “Everyone is paranoiac around here lately. There are rumors, rumors.”

Ask a student about the risk of arrest for marijuana users and he says, “The police have a list of heads on campus. I’m sure of it. This girl who was busted, and released with a stiff warning, told us all about it.”

Ask an occasional dabbler why his friends smoke marijuana in windowless apartments, instead of indulging in the privacy of dormitory rooms, and he will answer, “It’s got to be that way. Marijuana users are treated like heroin addicts out here. We’re the scum. The truth is that you couldn’t push heroin in the university if you parked a whole truckful out on the Mall. But the cops believe what they like to think is true, and they don’t care about what’s really happening.”

At the University of Wisconsin, unlike other Midwestern colleges which have drug users, student paranoia can be traced to a specific incident: “The Hellman thing.”

“Hellman wasn’t getting away with anything,” says one local policeman. “We knew all about the dope parties, and the girls he got to try drugs. We knew about his trips to New York. We knew more about the whole dirty business than they thought we did. And we were just about to close in on the whole mess, when he killed himself.”

Hal F. Hellman is alleged to have sold marijuana to the other students. Occasionally, it is believed, he himself experimented with more potent drugs. The policeman tells about the parties. He mentions a young agent who “infiltrated” Hellman’s social circle. “He worked his way in very well,” the policeman says, smiling. The police knew all about Hellman. A rich kid, a member of a prominent New York family, stuck out in the middle of Wisconsin with his $7,000 Jaguar, his books, his New York wardrobe. An airtight case. Hellman goes to New York and comes back with pot in his car. The agent is ready, the cops are ready, the university is ready.

And then Hellman shoots himself in the brain in his room at the Edgewater Hotel. It was an accident, the policeman says. “He was playing Russian roulette with a gun. He cocked the trigger, and it just went off before anyone knew what had happened.” A former student and an ex-convict were with him at the time; they were arrested for use of marijuana, and forgery, respectively, and later convicted. Beside the pot, the police found a copy of William Burroughs’s book about narcotics addiction, Naked Lunch. “That proves something,” the policeman says.

Hellman’s name is still frequently mentioned on the University of Wisconsin campus, even though his death occurred in 1963. “After the Hellman case, all the hippies were terrified,” one student says. “Everyone was sure that he was going to be hauled in.” And when students mention Hellman, they often dwell upon his town of origin. Hellman was a New Yorker. A migrant student.

On the university’s campus in Madison over 10,000 of the 29,000 students are from out of state, most of them from either nearby Chicago or the Northeast. This sizable urban subculture makes the University of Wisconsin one of the few places in the Midwest where, as one student says, “You can study without living with Midwesterners.” Students questioned on the Wisconsin campus estimate that 10 to 15 percent of them will have tried marijuana at least once during their four years at college, and the bulk of the experimenters will have come from Chicago or the East.

The heaviest concentrations of college drug-takers in the United States are in the Northeast and on the West Coast. Some Harvard students estimate that between a fifth and a half of them will try marijuana, or “pot,” at some time. Pot is easy to get in New York City, and on a number of New York campuses, including NYU, CCNY, Hunter, and Columbia. Chicago is a Midwestern drug-supply center. On rural campuses, particularly in the South, marijuana is usually rare and liquor is the accepted way to rebel. But many Eastern-city students now migrate for their college educations, and they have introduced marijuana to a number of campuses, including Cornell, Bard, Antioch, and Miami. At some, pot is used mainly by the migrant students; at others, its use has spread through the student body.

On almost all these campuses a sharp line is drawn between marijuana and other drugs. Marijuana is non-addictive, although it may be psychologically habit-forming. College students who smoke pot consider it the “safe way to rebel,” and they range from campus leaders to fraternity members to way-out “hippies.” Most of them use marijuana only occasionally. Some use it regularly but not heavily, somewhat the way other students drink beer on weekends. A small number are “heads,” or steady users, and these students are the ones most likely to go on to psychedelic (or hallucinatory) drugs like LSD. Almost none of the college drug takers use heroin. It is addictive and dangerous, and they are frankly scared of it. In college, addiction is considered uncool.

At Wisconsin most of the drug experimenters will live in the private apartments that ring the campus. Sometimes “straight” students call these people “grubbies,” and the Cardinal, the student newspaper, dubs them “Rathskeller Philosophers” after a cafeteria where they often gather. The “Bohemians” counter by speaking disdainfully of the “Langdon Street types” (the fraternities and dormitories, in which the in-state students often live, stand on tree-lined, residential Langdon Street). The clash between these two groups is most apparent in politics. But it also extends to social life. The Langdon Street types guzzle beer at bars like the “Kollege Klub,” while the grubbies smoke marijuana at small, private parties.

Mark Rogers [pseudonym], who comes from Chicago, sits in his apartment near the campus and talks about the two student cultures. “The Greeks [fraternity people] don’t mix with us except on certain rare occasions. This is not to say that they don’t ever turn on. What happens is that one of them tries it at a party and finds it supremely cool. Then he makes a connection and tells the brothers back at the house. So a few Greeks turn on. But it’s a once-or-twice deal. It’s like visiting a prostitute for them, and they tend to make much more of it than it’s worth.”

Mark picks up his cat, Bird (named after jazz musician Charlie Parker), and strokes him gently as he speaks of drug use among other students.

“This is the first generation to experience the opening up of drugs. Many people who turn on here now are the sons and daughters of the radicals who went to the university in the ‘Thirties. There’s the same motivation, I suppose. There’s the desire to experience the new. And there’s the desire to belong. You have the cell meeting, or the pot party, with the same sense of secrecy, of being part of the vanguard.

“Of course, the radicals were convinced they could change things around them through reform. The marijuana user only wants to change himself, and he doesn’t really care about the rest of the university or the world. The really ultimate thing is being satisfied by looking at your own toe.”

Mark sits in an old, faded easy chair in a typical student apartment. The floors and sinks are uncleaned, but the apartment features two excellent stereo phonographs, with stacks of jazz, folk, classical, and rock records. A half-dozen bookcases bulge with paperbacks. On the walls are prints, photographs, and portraits of heroes: the Rolling Stones, the Beatles, Bob Dylan, John F. Kennedy.

Mark shares the apartment with two Eastern students. There are also two girls, who live with Mark and one of the other students. When Mark and his city friends use pot, they do it casually. If they go to large parties, where “straight” people are likely to be present, they turn on beforehand so they won’t be ostentatious. Sometimes turning on is the natural conclusion to a dinner party. And sometimes the cat also turns on, although Mark says, “We try not to allow it because he starts chasing things up the walls and gets pretty uppity.

“Marijuana hasn’t changed my life,” he says. “Sometimes I wish it would.”

Mark and his friends are unlikely to become involved in a drug raid, since their experimentation is private and casual. And there is more than a little ridicule in their voices when they talk of police attempts at infiltration: “It gets to the point where all adults become automatically suspect. But somehow, you can always tell who the informers are. So we let them think they’re getting all kinds of information from us. I pity them. Spying on other people, it must be a lousy life.”

Mark’s statement comes close to being the official marijuana user’s view of the Madison police department. And the police are just as contemptuous of the students. In a police station in Madison, a narcotics official points with pride to a painting that hangs on the wall over his desk. It was drawn by a young police officer and shows drooling figures about to try drugs. In one corner a straw-like pile of marijuana is labeled MADE IN HELL. A snake-like figure is displayed, with outstretched tentacles and with his brain exposed. Above his head are demons, skulls, and ghosts. A pistol and a supply of bullets lie exposed on a table in a corner of the painting.