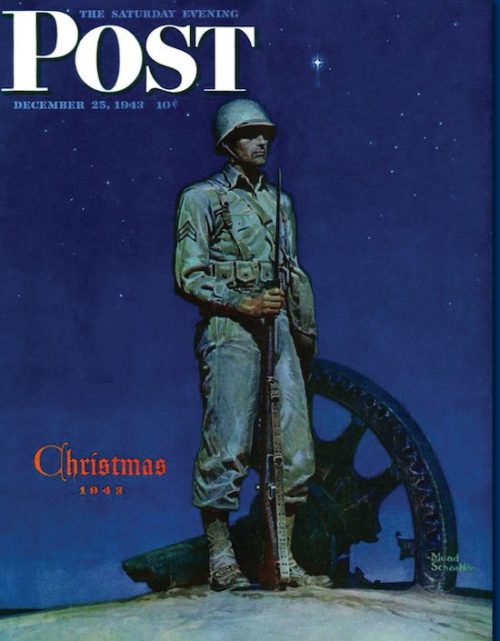

During World War II, two Saturday Evening Post illustrators, Norman Rockwell and Mead Schaeffer, wanted to aid their country’s war effort. They were too old to enlist, and neither one was physically suited to be a fighter, but they felt they might be able to help with their art.

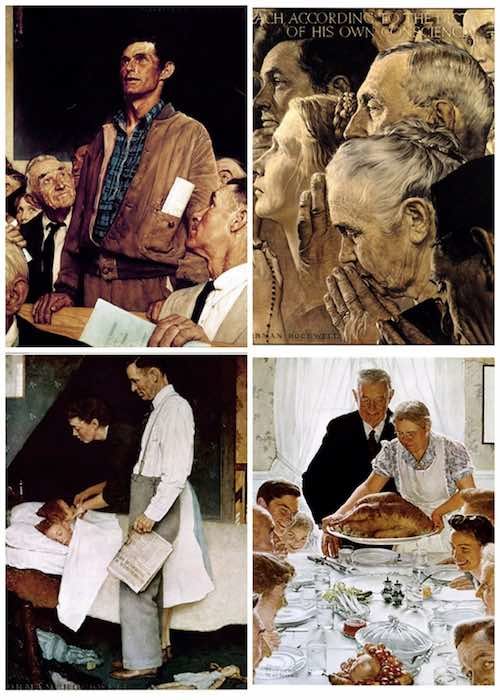

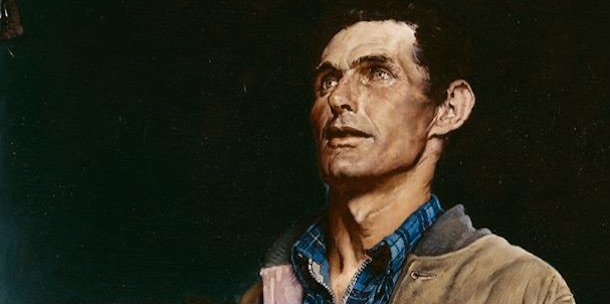

The two artists decided to paint patriotic pictures and offer them free to the Department of Defense for fundraising and enlistment campaigns. They worked hard developing their preliminary drawings; Rockwell decided to illustrate Franklin Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms” while Schaeffer chose a series of military themes. When they finished mapping out their ideas, the two took the long train ride from their studios in Vermont to the U.S. Office of War Information in Washington, D.C. The illustrators excitedly showed their proposals but met a frosty reception.

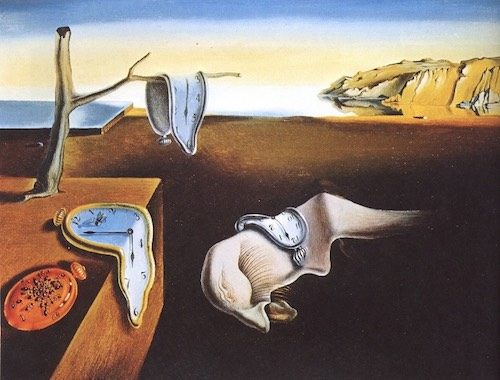

The Assistant Director of the Office was Archibald MacLeish, a famed poet, future Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright, and proud intellectual who didn’t think much of illustration. Rockwell recalled being told, “The last war you illustrators did the posters. This war we’re going to use fine arts men, real artists.” MacLeish thought the military should use artists such as Salvador Dalí, Marc Chagall, and Stuart Davis to inspire the American public.

The Pentagon was not totally unsympathetic to Rockwell and Schaeffer. According to Rockwell’s autobiography, it offered them a consolation prize: “If you want to make a contribution to the war effort, you can do…pen-and-ink drawings for the Marine Corps calisthenics manual.”

Stung, the two illustrators took the long, depressing train ride home to Vermont. Schaeffer’s family recalls that when Schaeffer’s wife learned of the rejection, she spoke up: “To heck with the Army, why don’t you offer your pictures to the Post instead?”

The illustrators turned around and took the train back down to the Post’s offices in Philadelphia. There, editors reviewed the preliminary drawings and agreed to run Rockwell’s paintings as internal illustrations, followed by Schaeffer’s paintings in later issues.

Rockwell’s Four Freedoms quickly became a national phenomenon. The Post received 60,000 letters about them. As editor Ben Hibbs later wrote:

The results astonished us all. … Requests to reprint flooded in from other publications. Various government agencies and private organizations made millions of reprints and distributed them not only in this country but all over the world. [Rockwell’s] four pictures quickly became the best known and most appreciated paintings of that era. They appeared right at a time when the war was going against us on the battle fronts, and the American people needed the inspirational message which they conveyed so forcefully and so beautifully.

It began to occur to government officials that they might have made a mistake rejecting the paintings. Belatedly, they tried to jump on the bandwagon. With Rockwell’s permission, the Treasury Department took the Four Freedoms on a tour of the nation as the centerpiece of a Post art show to sell war bonds. The paintings were viewed by 1,222,000 people in 16 cities and were instrumental in selling $132,992,539 worth of bonds.

The illustrations proved far more effective than anything else the government had planned. The Pentagon even sent a film crew to Vermont to stage a documentary about the illustrations, implying (falsely) that Rockwell and Schaeffer had been working at the behest of the government all along.

As for MacLeish, he did not last long in his job. Rarely has a misguided act of cultural arrogance been so promptly, resoundingly, and satisfyingly refuted.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

When I was growing up, we always had the latest Saturday Evening Post to read.