The news in early March of 1917 wasn’t good. Americans learned that German submarines were going to resume their attacks on all ships heading to England. Just days later, the U.S. government released the text of the Zimmerman Telegram, an intercepted message from Germany to Mexico. If the U.S. entered the war, it read, and Mexico declared war on the U.S., a victorious Germany would force America to return the territories of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona to Mexico.

Even before these news items, American opinion had generally turned against the German cause. It had been Germany, after all, who sank the Lusitania. And it was probably Germany who blew up an island in New York Harbor where the U.S. had been storing ammunition.

Now, as war drew closer, the country was growing more apprehensive about spies and saboteurs working for Imperial Germany. Many Americans suspected their German neighbors of being foreign agents. Pro-war propaganda in the newspapers helped to further demonize all Germans in Americans’ eyes. The public’s fears were shared by the federal government, which pondered how it would handle aliens from an enemy nation.

It was a problem that the U.S. would struggle with in subsequent conflicts.

In “Alien Enemies,” an article from the March 17, 1917, issue of the Post, author Melville Davisson Post describes how Great Britain developed its approach to handling German aliens. Based on Britain’s experiences, he recommends the U.S. take aggressive measures against anyone of German ancestry in America, including stripping naturalized German Americans of their citizenship and subjecting them to military justice. He also urges the forcible relocation of all resident aliens away from areas of military significance.

When war did come, President Wilson signed orders that labeled all Germans in America “enemy aliens.” He barred them from working in or near military facilities or Washington, D.C. This caused so many Germans to lose their jobs that the Labor Department feared a serious shortage of manpower.

All Germans had to register with the Post Office and carry identification papers at all times. German business owners had to open their account books to authorities. In several states, the attorney general ordered that Germans’ bank accounts be made public.

Several orders appear to have been motivated more by profit than national security. Late in the war, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer seized the assets of German companies in the U.S., which were then sold to Americans. And just days before the war ended, the U.S. confiscated the patent rights of Germans, which included the patents to valuable industrial chemicals and medicines.

The enemy alien laws affected 250,000 German men and 6,300 German women. Out of this number, the Justice Department’s Enemy Alien Registration Section incarcerated 2,048 Germans. Some, like Karl Muck, the conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, left America when released from camp and refused to ever return.

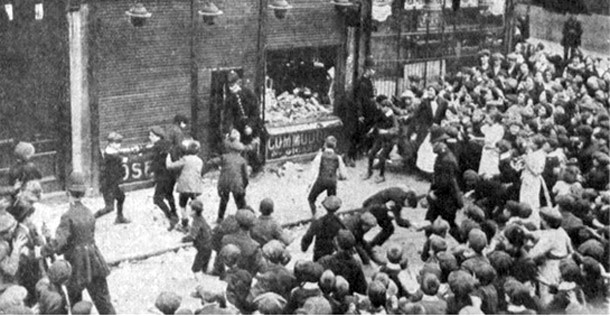

Those Germans who avoided detention endured harassment and vandalism from Americans throughout the war.

In later years, it became clear that the government’s actions against Germans had been excessive and did little to protect the country from enemy sabotage or subversion. Yet America was destined to repeat the mistake 25 years later with its Japanese citizens during World War II.

The author discusses Great Britain’s solution to the problem with German citizens living in England while it was fighting Germany. Though the U.S. wasn’t yet in the war, he believed German agents were already in America and recommended rigorous methods for isolating both Germans citizens and naturalized citizens from Germany.

Featured image: Photo from Brown Brothers, New York City, from “Alien Enemies” in the March 17, 1917, issue of the Post.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now