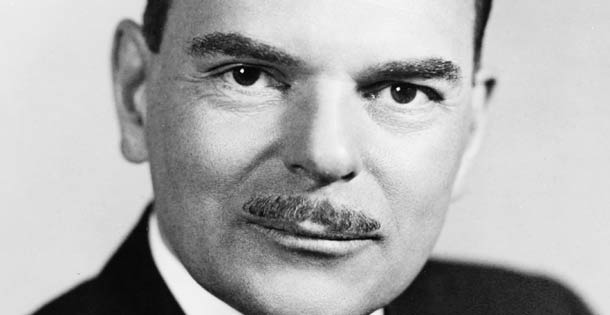

In 1948, Emilie Spencer Deer, a solidly Republican woman from Ohio, announced to her family that she would vote for President Truman instead of the Republican candidate Thomas Dewey because she could not vote for a man with a mustache. She was neither foolish nor alone in her opinion. Educated and conscientious, she was, like other women of her day, simply reading the signs of what a good man looked like at the time. A clean-shaven man was team player, whereas a mustachioed one demonstrated a willful independence that was not worthy of her confidence.

Emilie Deer was a voter in Ohio, one of three hotly contested states whose loss cost Dewey the election. In California, Indiana, and Ohio combined, Dewey lost by a mere 38,218 votes out of 8.6 million cast — just four-tenths of 1 percent. Had he won just over half of that tiny margin he would have become president. Indeed, the election was so close that the polls got it wrong and the Chicago Daily Tribune famously printed an errant early edition with the blaring headline “Dewey Defeats Truman.” The winner was only too happy to hold it up as a symbol of his come-from-behind victory.

It’s true that Truman had leveraged his populist “Give ’em hell” persona to rally the workingman behind the standard-bearer of the “Fair Deal.” There was, however, more to this confrontation than political policy. Dewey and Truman also offered voters contrasting images of masculinity: Truman complemented his trim, carefully tailored suits, and clean-shaven face with a warm smile, while Dewey appeared neat, but rather less congenial. Emilie Deer’s story suggests the additional facial hair may have been crucial in establishing a negative image of Dewey. More to the point, women judging male character may have determined the outcome.

At first, the mustache worked in Dewey’s favor. In the 1930s, he made a name for himself prosecuting mob bosses in New York, his home state, where his facial hair added to his reputation of forcefulness, and helped a self-conscious Dewey compensate for his short stature. One admiring male journalist effused that “in this clean-shaven age … [Dewey’s mustache] is little short of epic. It is fulsome, luxuriant, raven black, compelling, and curved in a way to gladden an artist’s eye.” Dewey was, in that writer’s opinion, “a Clark Gable of candidates” with more charm, personality, and political sex appeal than other Republicans. This was an overstatement. Dewey famously lacked the warm charisma of a movie star, and his mustache was not Gable’s dashing pencil trace, but a thicker and less distinctive brush.

Mustache murmurs began immediately, however, when Dewey launched his first campaign in 1944. Women writers were the most critical. After attending the Republican National Convention in Chicago that July, Helen Essary, a syndicated political columnist, declared herself impressed by Dewey’s intelligence and courage, but hopeful that the candidate would get himself to a barber right away. “I have heard dozens of women make the same criticism of the gentleman from New York,” Essary wrote. “It takes from the seriousness and strength of his face. Moreover it will not help with the women vote. … You see only the mustache. You remember only the mustache. Without it, Governor Dewey would look a million percent more real as the proper man for the White House job he is after.”

Edith Efron, writing in the pages of The New York Times Sunday Magazine in August 1944, also concluded that Dewey “may be elected to office, but it will be in spite of his ‘manly attributes’ — not because of them.” To Efron, it seemed clear that whatever reasons a man had for wearing one, a mustache had a profound, often negative effect. “It plays many roles today,” she wrote. “It is Chaplin-pathetic, Hitler-psychopathic, Gable-debonnair, Lou Lehr–wacky. It perplexes. It fascinates. It amuses. And it repels.” Those writers who defended Dewey, usually male, agreed that mustaches marked an assertive type of man, but they read this as a positive quality.

From the female writers’ perspective, Dewey failed to meet the standard of modern manhood. In the early 20th century, shaving was, along with an appropriate suit, tie, and hat, a sign that a man was a conforming member of the masculine collective, whether it was the army, a company, or a sports team. Hollywood already knew what Dewey did not. Women in general would rather not see a leading man with facial fuzz. In the late 1930s, after evaluating the reaction of women in test audiences to actors with and without a mustache, the big studios advised their male stars to stay shaved.

When he ran again, in 1948, Dewey trimmed back his already modest mustache, but it still loomed large in perceptions of him as a candidate. Once again, female columnists raised objections while Dewey himself preserved his dignity by ignoring the issue. Only after the election, he explained to a female voter in New York that shaving had irritated his lip, and when he let it grow, his wife liked it. He left it to others to respond to popular suspicions that the mustache affirmed his reputation for arrogance. One obliging columnist insisted that the nominee was not affecting “a trick trim … like some movie actors have. The Dewey mustache is merely a part of him.” While Dewey’s hairy lip contrasted in some respects with his generally dull and stiff manner — as one wag put it, like a swear word in an unexpressive sentence — the whole package created the impression of a man who was both willful and aloof.

Dewey’s defeat helps explain why he has been the only major candidate since 1912 to sport facial hair. In the era of television and the internet, voters have increasingly relied on physical cues to assess a candidate’s qualities, and voters in our own day still tend to interpret the male face as they did in the 1940s. A recent study suggested that women are less likely to support a bearded candidate, and when former contenders Al Gore and Paul Ryan grew beards, it was readily interpreted as a retreat from presidential ambitions. Even in Canada, shaving off the beard can signal a serious run for office, as in the case of Canada’s new prime minister, Justin Trudeau.

After his near miss with destiny, Dewey seems to have been aware that his mustache had cost him support. In 1950, the wistful governor told a visiting group of Boy Scouts, “Remember fellows, any boy can become president — unless he’s got a mustache.” It was a joke — sort of.

Christopher Oldston-Moore wrote this for What It Means to Be American, a national conversation hosted by the Smithsonian and Zócalo Public Square. Originally published at Zócalo Public Square.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now