“Is anything about World War I even relevant today?”

I’ve often been asked that question since I began this blog last fall. I’ve asked it myself. Is there anything we can learn from 100-year-old wartime experiences?

After reading “War and Hallucinations,” by Corra Harris, I can now answer with an assured yes. Because Harris, though writing 100 years ago, describes the challenge we still face in coming to terms with war and terror.

Back in 1915, American newspapers continued to publish atrocity stories from Europe. The German army was accused of mass executions, rape, and slaughtering children. Journalists couldn’t confirm or deny the reports coming out of Europe, but that didn’t prevent American newspapers from repeating the stories.

Harris didn’t believe the horror stories. Rather than recount them again, she gave her opinion of where they came from, and why so many people believed them. The war, she wrote, had caused the people of Belgium, France, and England to lose some of their sanity:

From the day I entered the war zone till this one upon which I take my departure from it I have been aware of a certain psychic condition, difficult to describe yet so powerful that no one can escape its influence … as if all thought had lost its shape, and reason was no longer reasonable. As if all men and all women were somnambulists walking in a black dream.

They speak with calmness of things so horrible that one is amazed that they do not shriek and wring their hands. And one is still more amazed at having the power to listen with calmness. We see terrible sights, we hear of them, we think of nothing else, and yet we do not go mad. For where everybody is mad no one is.

The French newspapers had carried the news of thousands being killed at the front, and an unstoppable German army was marching on Paris. Fear overpowered reason. The citizens’ anxieties were fed by the terrifying stories — “hallucinations” Harris called them — from refugees arriving in the cities.

Harris described Lille refugees traveling for days, defenseless and hungry, with artillery fire from both sides exploding around them. They knew the Germans were right behind them, and they weren’t permitted to stop in towns along the way. They might collapse in exhaustion in a ditch for a few hours’ sleep, but they’d awake at a strange sound or a suspicious form in the darkness. And as they resumed their march, they picked up bits of conversation from other refugees to weave them into their own fearful imaginings.

When they finally came upon relief workers, they recounted their journeys with a vividness that reflected their terror more than their reality. “The awful thing about war for the helpless,” she wrote, was that war “is what they fear, intensified by the horrible things they have heard.”

It wasn’t just refugees. Harris remembered soldiers claiming to have seen 10,000 men killed every day in one battle. The rivers near Calais, they said, were clogged with the bodies of dead Germans. Calmer observers coming on the scene after the fighting found nothing to justify these claims. These “hallucinations” were the attempts of Frenchmen, who had led routine, peaceful lives before the war, to describe the spectacular horrors of what they’d seen.

(Wikimedia Commons)

“When 70,000 Indian troops landed at Marseilles it was incredible,” Harris added. “The sight fired the imagination, so we heard that a force of 800,000 Japanese were already on their way to join the Allied Armies. Only 800,000! You get the contagion for using big numbers from reading the papers and from listening to the average man talk. Figures, which in normal times are supposed not to lie, have become the medium of fiction in this war.”

This exaggerated language was another sign of the derangement from war, Harris wrote. “Language is … designed to convey the commonplace meanings of life.” But the Europeans were experiencing such atrocities that their minds were “completely divorced from reality, because reality itself surpasses the power of even imagination to conceive.” And language became “the war currency of a bankrupt nation. It has no value. All the lies that words can frame are floating in this atmosphere. The truth itself is the greatest fabrication of all, because it belies all we have called truth.”

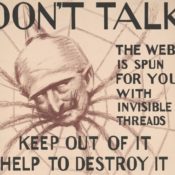

Today, it’s difficult to keep a sense of proportion when we think of 9/11, the Boston Marathon bombing, or the grisly murders of captives in the Middle East. We calmly discuss these events, and even try joking about them, as if to laugh off our worries. But the uncertainty and anxiety remain because the limits of the-worst-that-could-happen have been pushed far back. Faceless enemies and random attacks have eroded our sense of what to expect, or whom to trust. When reason can’t make sense of our world, dread and fear can take over.

As Harris noted in 1915, “Every ideal by which men aspired and lived is changed. Nothing is familiar and no man is sane — because imagination rules.”

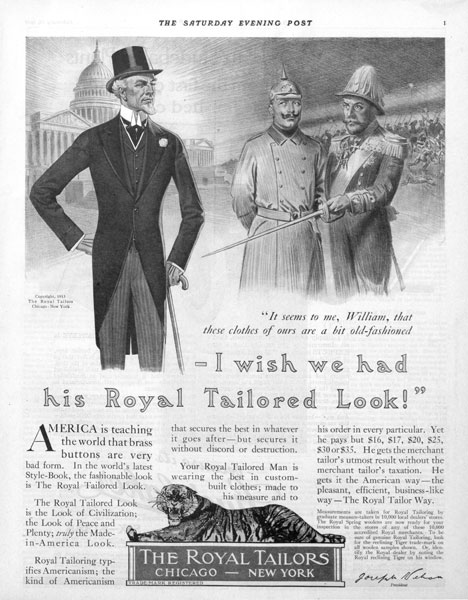

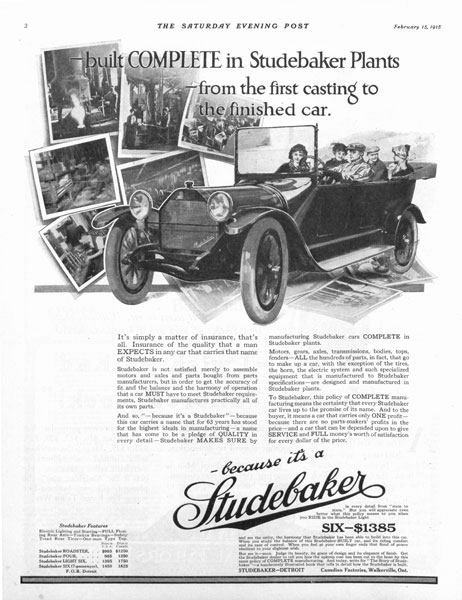

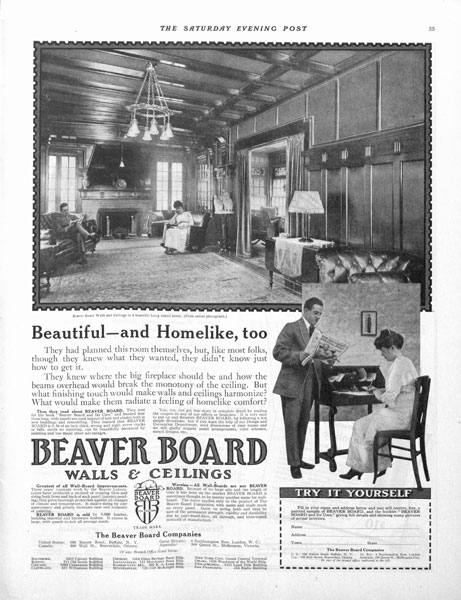

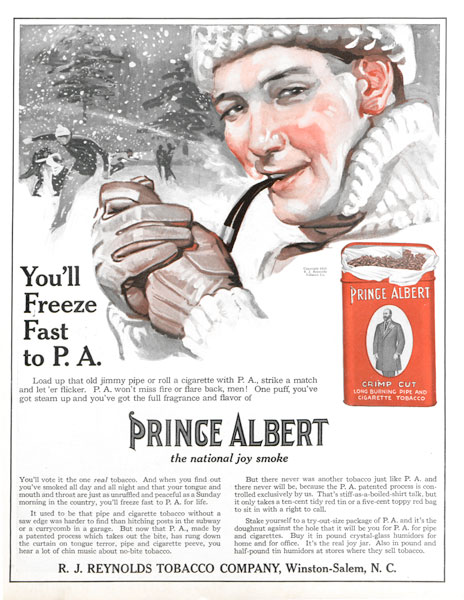

Step into 1915 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post February 13, 1915 issue.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Handsome historian on V-Day.