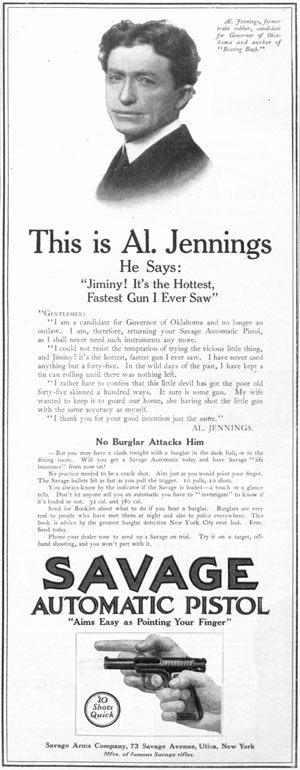

“Jiminy!” wrote Al Jennings. “It’s the hottest, fastest gun I ever saw.”

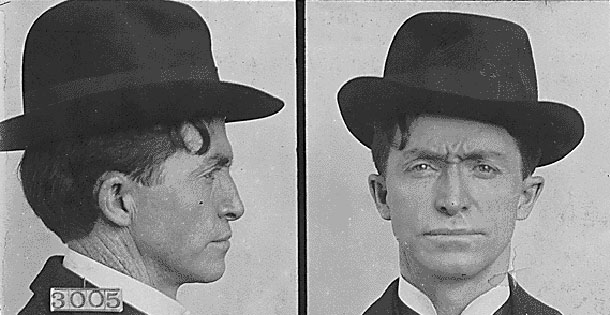

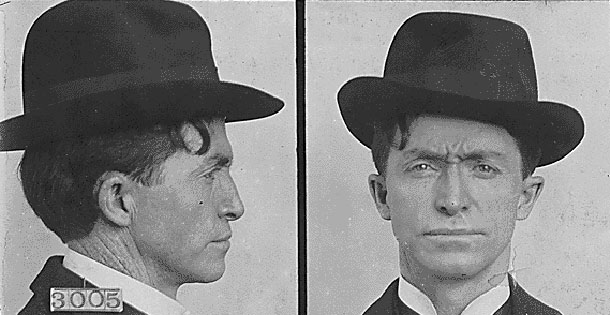

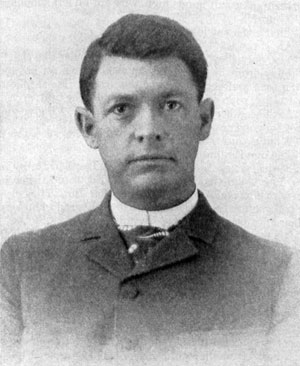

The gun was a pistol made by the Savage Arms Company. Jennings, the man singing its praises in a 1914 ad, was a former cowboy and lawyer who’d recently entered politics. What made his opinion about guns valuable was the fact that he had also been a train robber. In the 1890s, he’d led a gang that committed several robberies in the West. Captured and sent to Ohio State Penitentiary, he spent three years in prison before being pardoned.

At the time the Savage ad appeared in the Post, Al Jennings a strong contender for the Democratic nomination in Oklahoma’s election for governor. His campaign made no secret of his past. In fact, it helped distinguish him from the other Democratic nominees. It also won him the support of male voters (women couldn’t vote for another six years) who still viewed outlaws as champions of personal freedom.

The myth of the noble robber was firmly established in America’s popular culture by 1914, supported by hundreds of dime novels and theatrical melodramas. Criminals were often depicted as romantic heroes: independent, courageous, and gallant. Certainly that’s how Jennings presented himself in his memoirs, Beating Back.

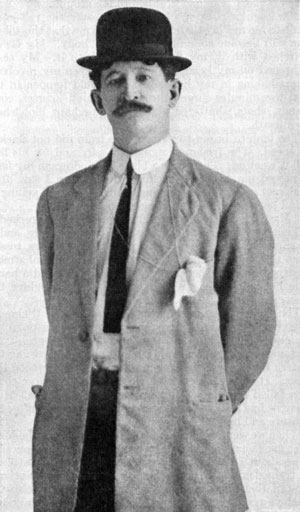

And that’s how he was viewed by Will Irwin, a seasoned journalist and frequent contributor to the Post.

Irwin had met Jennings by chance at a New York drama club and been intrigued by the man’s story. He helped Jennings write his autobiography, then took it to the Post, where it was serialized over seven issues.

Jennings’ story had all the qualities of popular melodrama. A proud young man turns outlaw after his brother is killed and the law does nothing to bring the killer to justice. He becomes a fearless train robber, but remains chivalrous and fair-minded. Eventually he is betrayed, shot, captured, and tried. Sentenced to life imprisonment, he refuses to be intimidated by other prisoners or prison officials. His fearlessness and quick wit earn him the reputation of a man who can be trusted. Then a high-ranking politician befriends him and helps him obtain a pardon. Returning to the West he starts life over, and runs for office—the bad boy who makes very good.

Now, Will Irwin was no kid. He should have known the difference between the dime-novel hero and a plain old crook. A graduate of Stanford University, Irwin had written for several newspapers and national magazines before meeting Jennings. I would expect him to have listened to Jennings’ tales with a hard, professional skepticism. Yet he seems to have swallowed Jennings’ tale and even made excuses for his crimes.

“In his infancy he had found a hostile world arrayed against him and had learned to battle for his rights,” Irwin wrote in the first Beating Back installment. “Such a complex nature as his cannot be expressed by any formula. … But one factor does something to explain it — his aristocratic Southern blood.”

As Irwin portrays him, Jennings is a member of the proud class of Southerners who clung to their code of honor after the Civil War: “Burning with the chagrin of defeat, convinced of the justice in their lost cause, stripped of their slaves and property, born or reared among the hideous disorders of a devastating war, they brought West not only their courage but also their belief in the duello as a corrective against the transition from a feudal state to an industrial state. To this type Al Jennings had bred true.”

Perhaps Irwin got those notions about chivalrous Southern nature from Jennings, who told him, “That high, proud, overbearing blood has a lot to do with the way I acted. When such people are picked on, they believe in their bones that it’s right to tear up the whole earth to get even.”

Jennings’ memoirs offer details about his gang and how they held up trains, yet he leaves several important points unexplained. For example, how and why was his brother killed? Why did he run from the law after his brother’s death? Why, exactly, did he become a robber? If his fame as a train robber was so great, why is his name almost unknown today?

Jennings didn’t address these questions, but a modern-day crime writer has. Jay Robert Nash has published dozens of books about crime and criminals. In his Encyclopedia of Western Lawmen & Outlaws (De Capo Press, 1992), he offers an interesting counter-history to Jennings’ memoirs. (Unfortunately, his account doesn’t offer any documentation, so we only have his word to weigh against Jennings’.)

Nash even gives a different account of the reason Jennings took up crime. It begins with two of Jennings’ brothers, Ed and John, who were lawyers. In 1895, Ed and John were in court, defending some men accused of theft. The prosecutor was Temple Lea Houston, son of Texas’ Sam Houston. During the trial, the Jennings brothers exchanged angry words with Houston.

That evening, Ed and John — who’d been drinking heavily — confronted Houston in a saloon. They challenged him to a gunfight and started to draw their guns. Houston shot John in the arm. John’s shot struck and killed brother Ed.

On the day Ed was buried, Al was frantic to exact revenge on Houston, even though Houston hadn’t killed his brother. Jennings’ father, a respected judge, warned him against such foolishness. Furious at being checked by his father, the young man packed his belongings and rode away. Shortly afterward, he held up a grocery story, thus launching his criminal career.

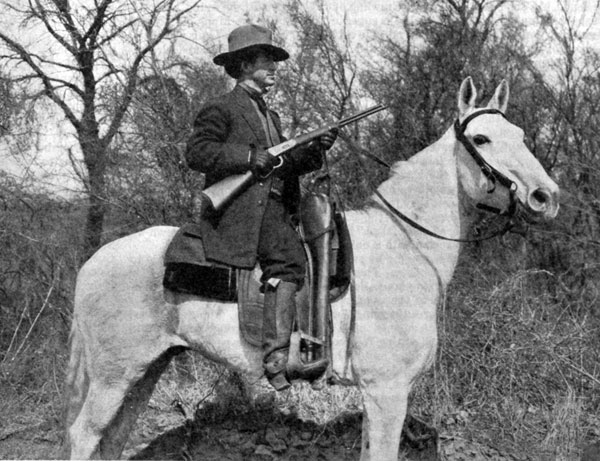

In Beating Back, Al Jennings tells how he built a gang of like-minded cowboys with brother Frank. Soon, he claims, their fame spread throughout Oklahoma. The Jennings gang became “notorious … every robbery of every kind was attributed to us.”

But in Nash’s account, Jennings was a disgrace to the train-robbing profession.

In one robbery, Al stood frantically waving a red lantern over his head in the middle of the railroad tracks, intending to halt and rob a train. But, writes Nash, the locomotive’s engineer didn’t even slow down. Jennings jumped back just in time to avoid being hit.

On another robbery, he used so much dynamite to blow up a mail-car safe that he reduced the safe, its contents, and the entire railway car to splinters. In a third robbery, he and his brother Frank galloped alongside a train ordering the engineer to stop. The engineer, Nash writes, “waved a friendly hello, and kept going. The Jennings brothers, their horses exhausted, fell behind and then came to a panting stop.”

In Al Jennings’ book, he gives three reason for his capture: (1) he was suffering from a gunshot wound; (2) he was betrayed by a friend; and (3) he and Frank were surrounded by a dozen armed lawmen. According to Nash, Jennings was captured when an Oklahoma marshal found him and Frank hiding under a pile of blankets in the back of a wagon. “The boys meekly surrendered,” Nash writes.

Jennings becomes even less believable in his account of his time in prison. He wrote that he arrived at the federal penitentiary in Ohio to find his reputation had preceded him. Everyone — prisoners, guards, and officials — seemed to know and respect him. Occasionally, a warden or trustee tried to bully him, but he always fought back and won. And the few men he didn’t frighten were won over by his intelligence, courage, and integrity. Eventually, he was befriended by the penitentiary warden, who called Jennings his “trusted advisor.”

In 1914, a movie company produced a film version of Beating Back, which was released just prior to the Democratic primary election in Oklahoma. Al and his brother Frank starred in the production. And the film probably won more votes for Jennings, but not enough to win the nomination. He came in third place.

The experience seemed to have taught Jennings that his future lay far beyond Oklahoma City. He soon moved to Hollywood to continue acting and to become a technical advisor for Western movies. His expertise might have rested on nothing more than his imagination, but it was just what Hollywood wanted.

Maybe Al Jennings did none of the things he claimed. Maybe he was incapable of planning and executing a successful train robbery. But we should recognize one skill Al Jennings certainly had. He could charm people. He was able to make people like him and, even more impressive, believe him. He had the ability to convince strangers that he was that romantic fantasy: a fearless criminal with morals and a heart of gold.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now