Joseph Christian Leyendecker wasn’t the first artist to use an infant to represent the new year. But over the span of 36 years, he made the New Year’s baby as familiar to Americans as Father Time.

A consummate illustrator — and mentor to Norman Rockwell — Leyendecker was continually searching for better ways to depict the holidays. He created many fanciful covers that caught the spirit of Christmas, Fourth of July, Easter, and Thanksgiving. But the New Year’s babies are arguably his most memorable.

The 1900s

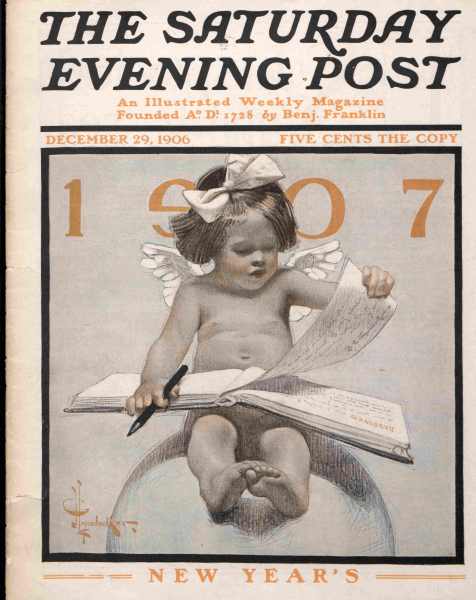

His first baby was delivered for the December 29, 1906, issue of the Post. It shows a cherub atop a globe, turning over a fresh page in a book of New Year’s resolutions. The series continue without interruption until 1943.

Not only do the New Year’s covers showcase Leyendecker’s unmistakably realistic style, but each one insightfully captures the spirit of the times.

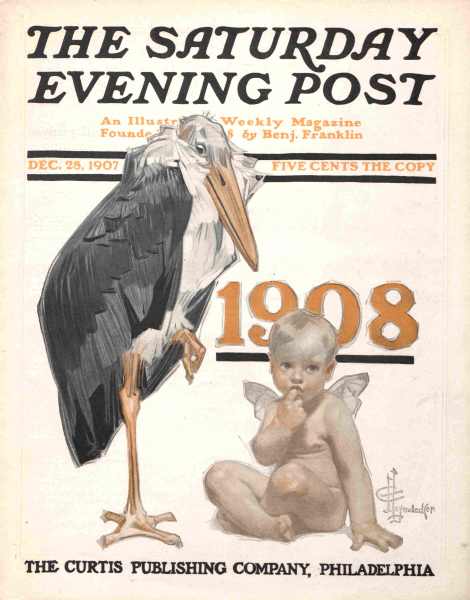

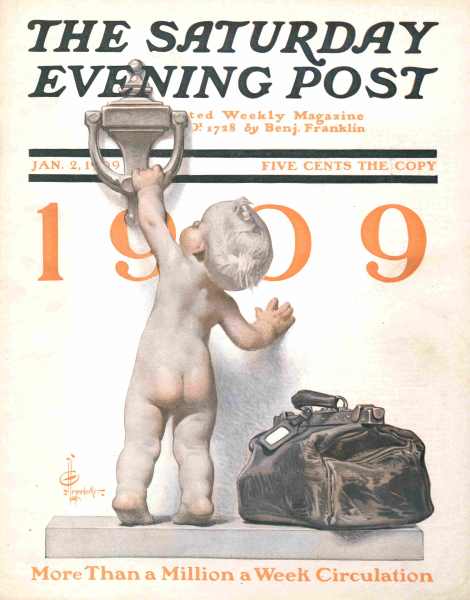

Look closely and you’ll notice that Leyendecker painted a baby in some years and a cherub in others. There doesn’t appear to be any logic to Leyendecker’s annual choice – except that, for some covers, his design sense required the figure to have wings.

1900s – Click cover to see larger image.

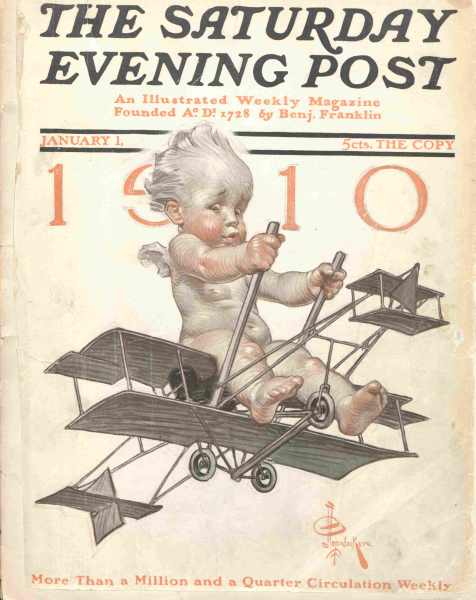

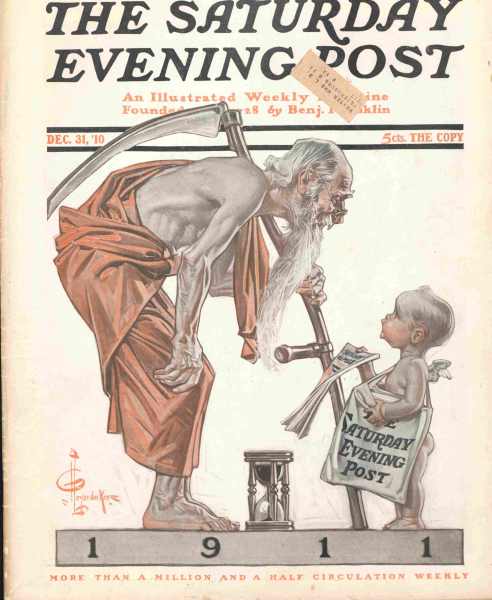

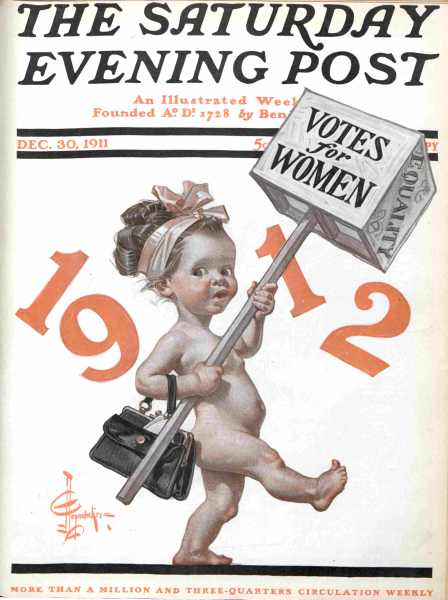

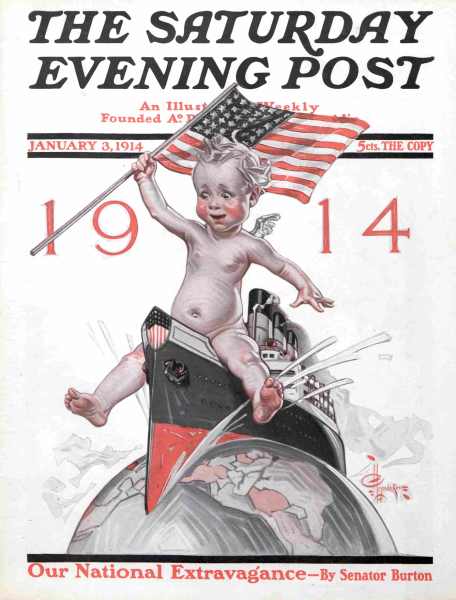

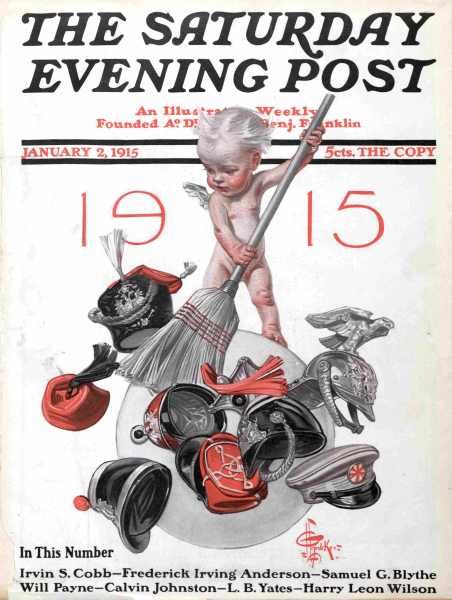

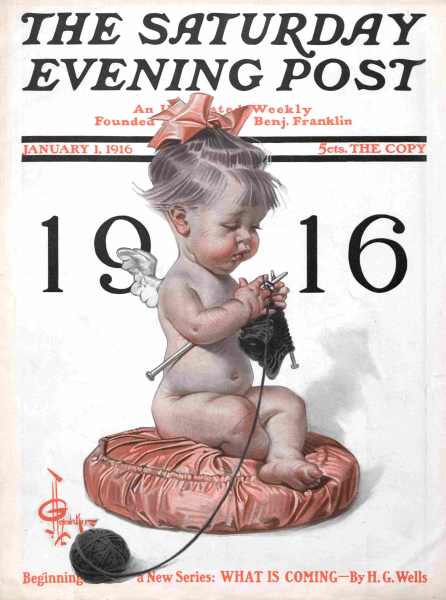

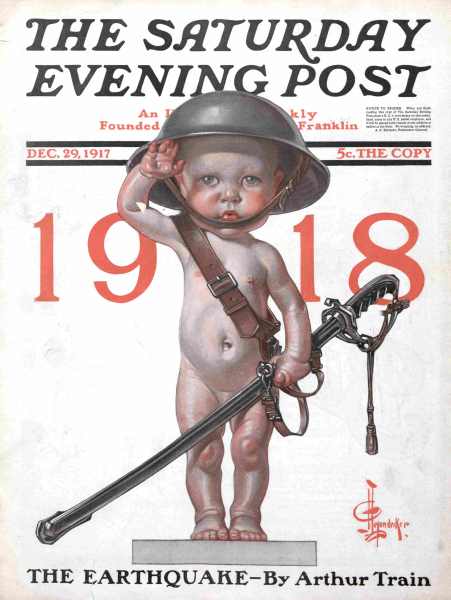

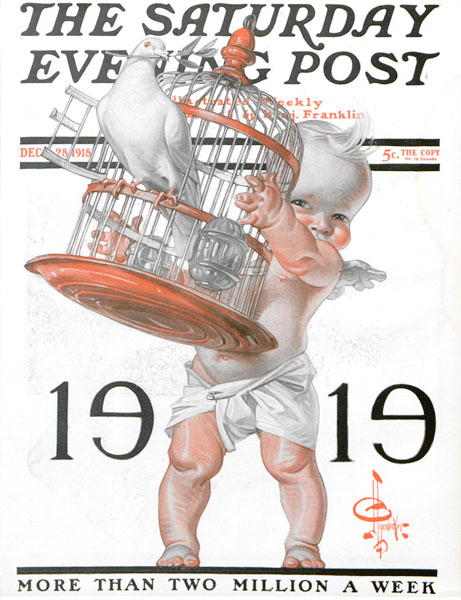

The 1910s

Starting in 1910, Leyendecker’s New Year covers began incorporating contemporary events. The 1910 cherub reflects America’s growing fascination with air travel and anticipates the country’s first airshow in Los Angeles. The 1912 baby takes up the cause for women’s suffrage. A flag-waving 1914 cherub celebrates the completion of America’s canal across Panama, which would open that August. The 1915 cherub tries to sweep the globe clean of the armies at war in Europe, represented by the military caps and helmets of the combatants. The 1917 cherub fretfully regards the explosive events in western Europe just three months before the U.S. enters World War I. A baby was seen reporting for duty in 1918, but in 1919, a cherub appeared, six weeks after the end of fighting, bearing the dove of peace.

The 1910s – Click cover to see larger image.

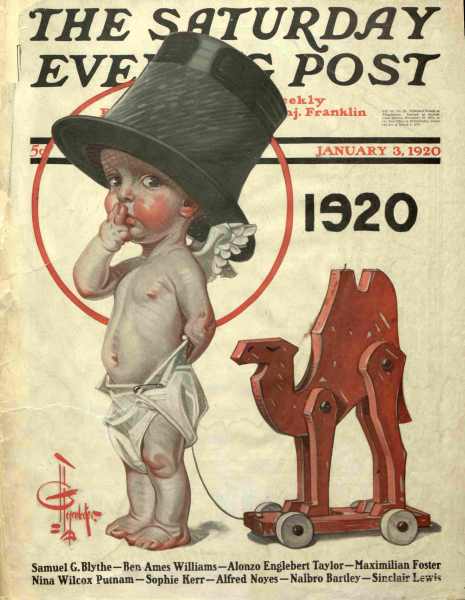

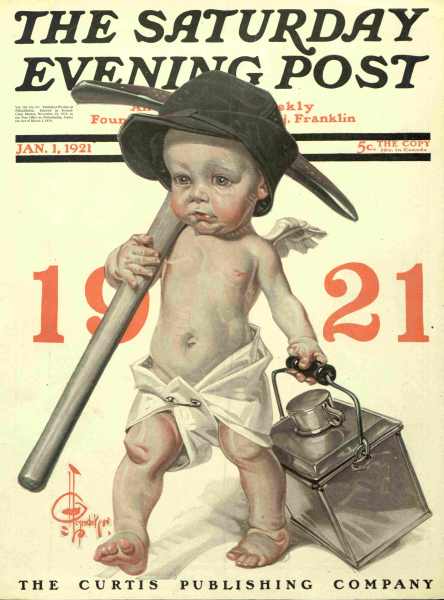

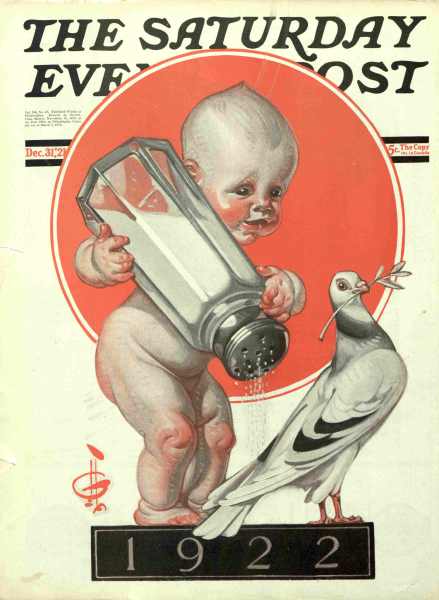

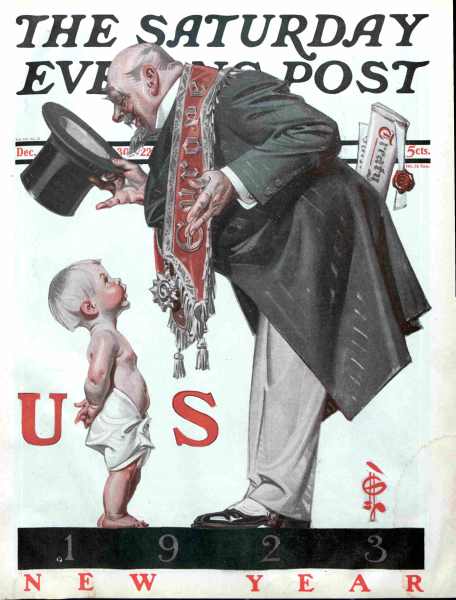

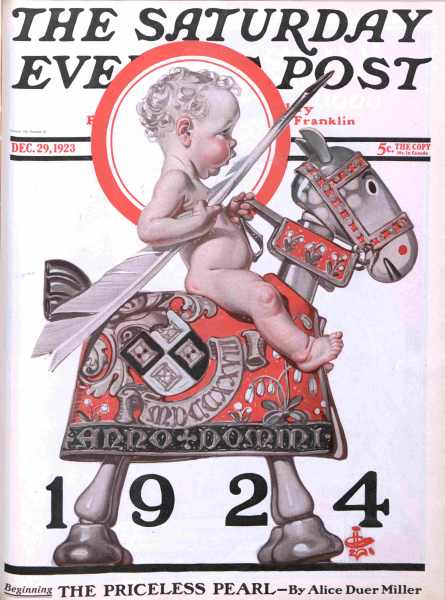

The 1920s

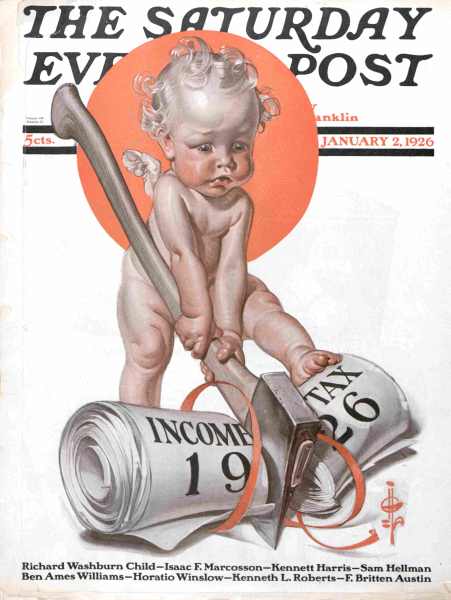

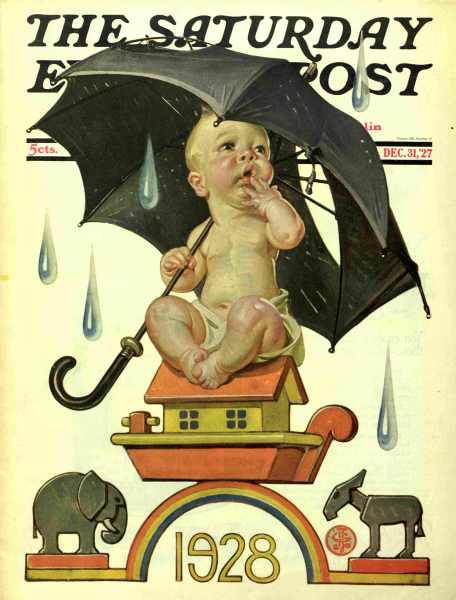

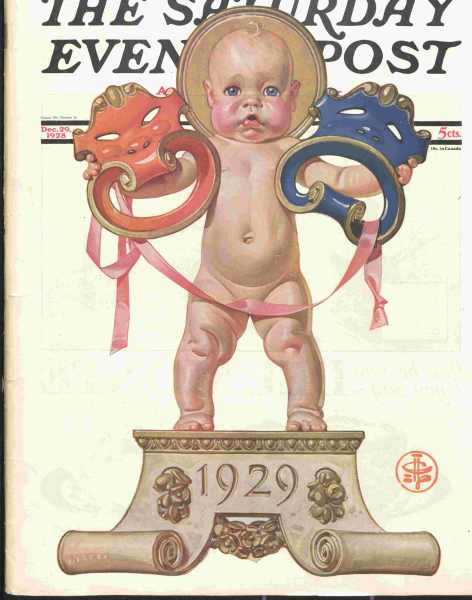

The ’20s saw the start of Prohibition, so Leyendecker’s first cherub of the decade wears a top hat – a reference to the well-known Prohibition cartoon character Mr. Dry – and carries a camel pull-toy symbolizing the long dry spell ahead for America. The 1921 cherub anticipates an end to the bitter coal miners’ strike in Alabama. The New Year’s baby trying to capture a dove – the symbol of peace – by salting it’s tail in 1922, is hoping for the Washington Naval Conference to reduce naval armaments among nine nations. The 1926 cherub anticipates the new Revenue Act, which reduced inheritance and income taxes. Sitting on the ark, the 1928 baby awaits the possible repeal of Prohibition, symbolized by “wet” weather. During a teetering economy in 1929, the New Year’s baby holds theatrical masks, uncertain of whether the coming year will be comic or tragic.

The 1920s – Click cover to see larger image.

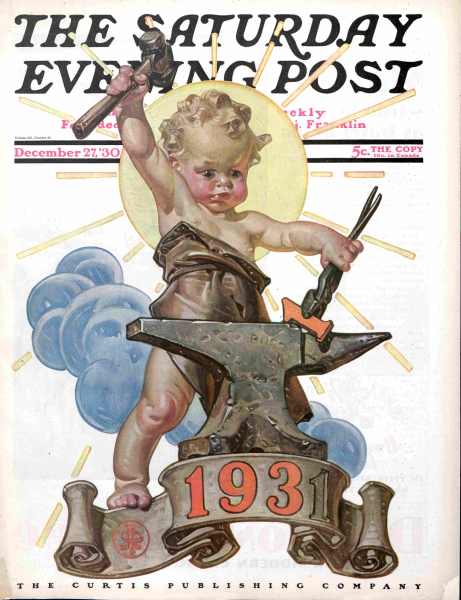

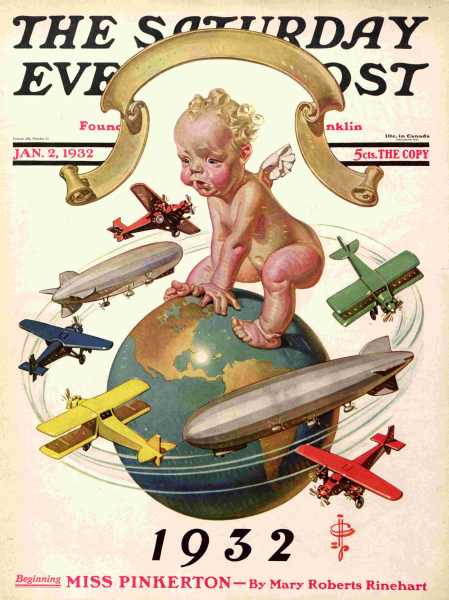

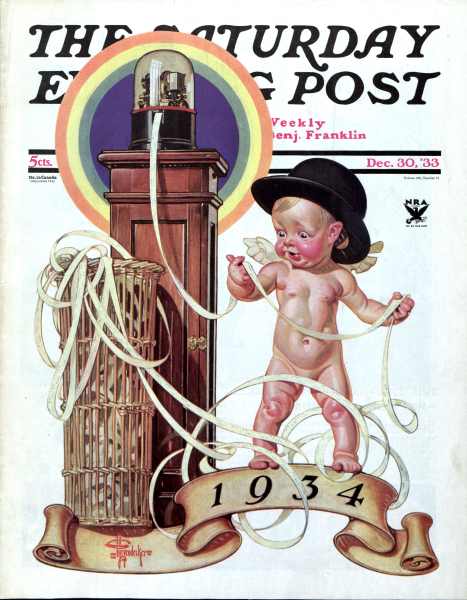

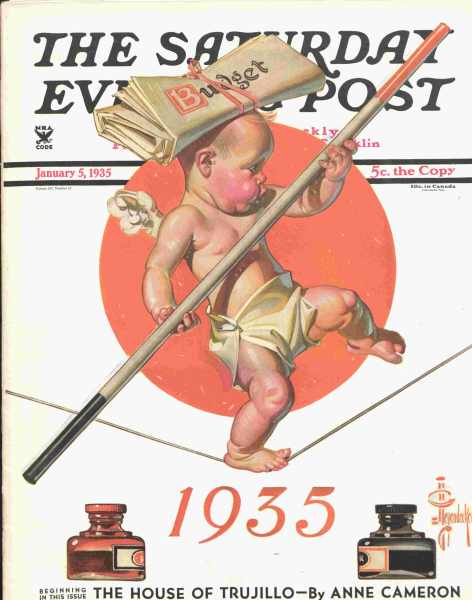

The 1930s

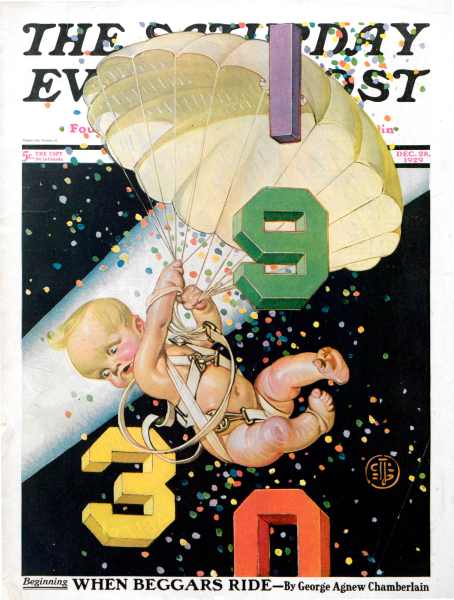

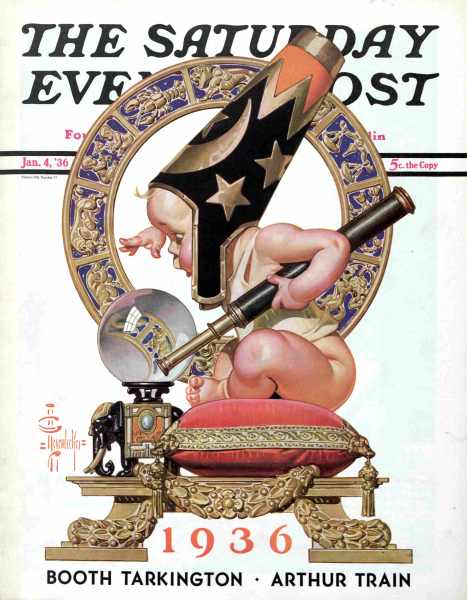

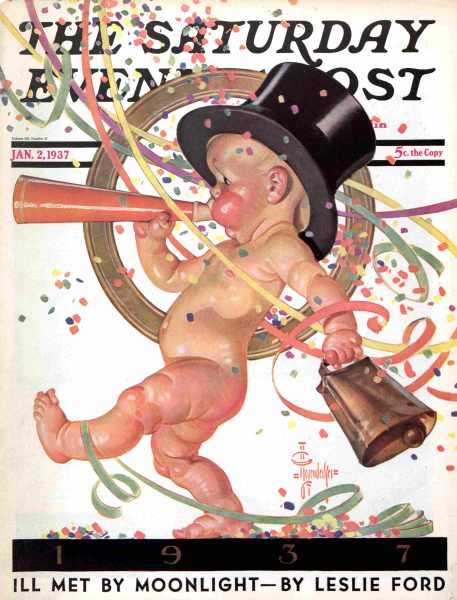

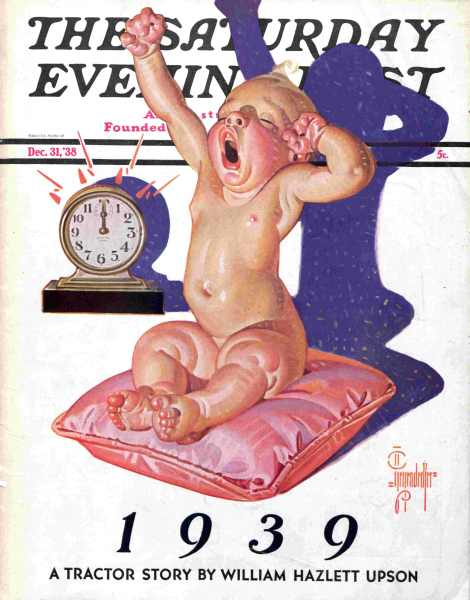

Arriving just two months after the collapse of the stock market in 1930, the baby worried how he’d land in the new year. In 1933, he was recording a desired rise in stock prices. Wearing a businessman’s bowler hat in 1934, he nervously watched a growing pile of stock ticker tape, while the blue eagle of the National Recovery Act hovered over his shoulder. The cherub set out to negotiate 1935 on a fiscal tightrope, between the red ink of debt and the black ink of profit, while precariously balancing a budget on his head. No longer trying to work the numbers in 1936, the baby was looking for the return to prosperity in his crystal ball. Finally, in 1937, when America’s leading economic indicators were approaching late-1920s levels, the New Year’s baby allowed himself a little celebration. By 1938, he had returned, deep in thought, to the anvil he had been pounding in 1931.

The 1930s – Click cover to see larger image.

The 1940s

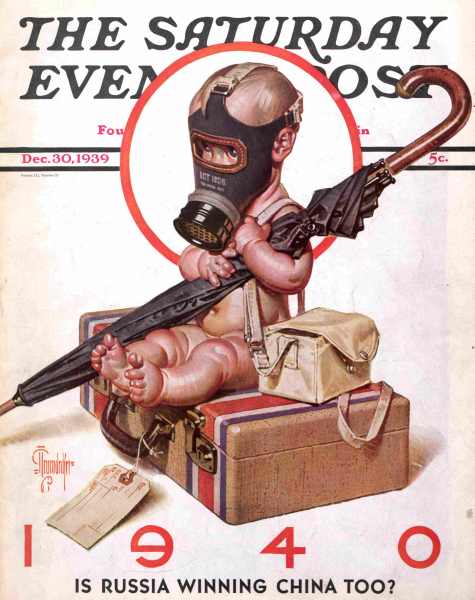

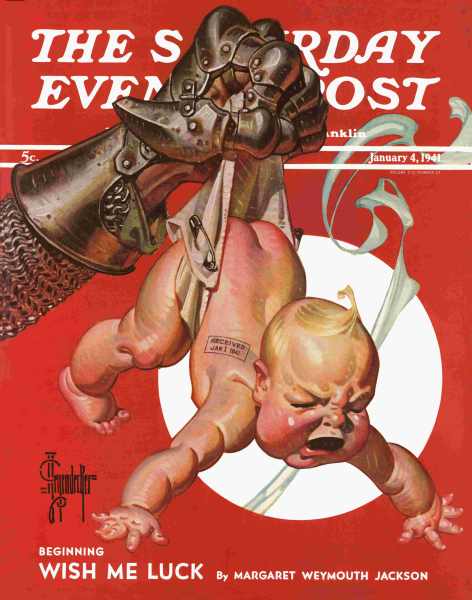

Although the country was at peace in 1940, Americans were growing worried that they would again be dragged into Europe’s conflict. The New Year’s baby was taking no chances. He arrived with his belongings packed, ready to move at a moment’s notice. Meanwhile, he wore his gas mask and clutched an umbrella, a symbolic reference to British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain whose assurances of “peace in our time” proved illusory. The 1941 baby was delivered by the armored fist of war.

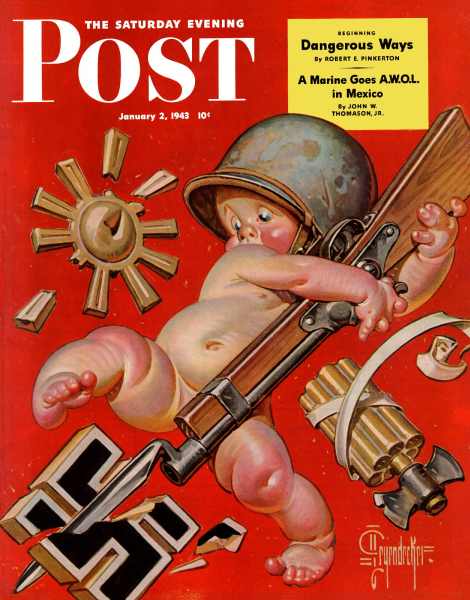

The New Year’s baby of 1942 had probably been painted before Leyendecker heard of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7; the cover shows a wary New Year’s baby wearing a U.S. Army garrison cap and guarding the Western Hemisphere from the spread of European and Asian wars. By 1943, Leyendecker’s baby had come a long way from his early, innocent days. Awkwardly yet enthusiastically, he tears into the symbols of the Axis powers – the Japanese sun, the German swastika, and the Italian fasces. Unfortunately, Leyendecker didn’t continue his series to bring the New Year’s baby out of the war and into peace again. This was his 324th, and last, Post cover.

1940s – Click cover to see larger image.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I PARTICULARLY LIKE THE 1939 ILLUSTRATION – THE YEAR I WAS BORN. LOOKS JUST LIKE ME.

Thank you for doing this feature, Jeff. I love them all. In a way I’m sorry he didn’t continue the tradition past 1943, but he ended the series in what is arguably the most dramatic way possible.

I’m not sure if it would have lent itself to the years after World War II, or the 1950’s and after. Perhaps Leyendecker somehow sensed that during this middle year of the war, and decided to ‘retire’ the infant with that final red 1943 cover.

I enjoy reading the Post’s interesting articles and the jokes. I remember reading the Post when I was very young. I loved it then and I love it now….70 years later.

New Year’s Eve reminds us about our personal history as well as that of the world around us. Happy New Year to you, Mr. Nilsson!