On September 26, 1914, the Post published an introduction to aerial combat and the new fighting “aeroplanes” of the war and a look inside wartime in Paris.

The Air Fleets

By Glenn Curtiss

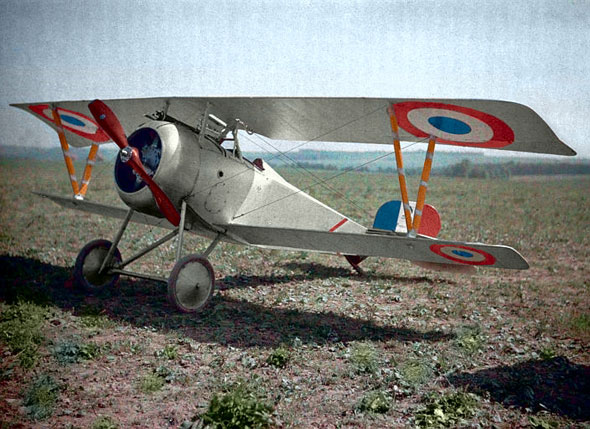

The Post’s very first article on air combat was written by aviation pioneer Glenn H. Curtiss. Not only was he familiar with the various styles of planes being used by combatants, he could also anticipate the terrors that pilots would face in dogfights long before any had taken place.

“The awfulness of this combat can be imagined by those only who, through personal experience in the upper air, have come to realize the insignificance of objects or individuals in this practically limitless space. Away up there, in machines speeding at the rate of nearly two miles a minute, men need in the clearest weather be but three or four minutes apart to be hopelessly lost from sight of one another; in hazy or cloudy weather an enemy may be within easy striking distance before he is either seen or heard.”

“England is at present the acknowledged leader in the development of [reconnaissance planes] The business of these machines is just what the name suggests. Fast enough in horizontal speed to escape any antagonist seen in reasonable time, they will sail leisurely over the enemy’s lines, while the observers … make accurate records of the disposition of the enemy’s forces. The observer is armed with a quick-firing rifle … though as most of them are tractors, the observer cannot fire at machines directly in front of him, but would have to shoot from above, below or nearly broadside.”

Paris When the War Broke

By Samuel G. Blythe

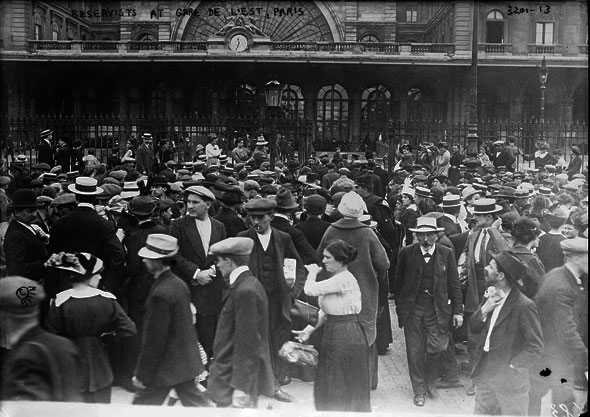

A week after publishing his account of wartime London, the Post printed Blythe’s report on Paris. He was surprised to see the demonstrative French respond to the war crisis with calm, almost grim determination.

“With the soldiers marched their wives or their sweethearts, or ahead of them, or behind them, cheering their husbands or their lovers on to war. One woman, going to the railway station with her husband, threw their baby into the soldier’s arms just as the train left. ‘Leave him with the station master at the first stop,’ she cried. ‘You may never see him again, and I’ll go and get him.’

“… It is at night that the greatest change is noticed in Paris. The city is silent and deserted after 9 o’clock. The streetlights are maintained, but the streets seem darker than usual, because electric lights are forbidden in shops and cafés after 9 o’clock. All residents of Paris are supposed to be in their homes at that time. The street cafés, that customarily are open always, are closed at 9. In the first days the tables outside the café were forbidden, but now the Parisians are allowed to sit at the little marble-topped tables during the day and sip their grenadine and discuss the war. Most of the harsh-voiced news-venders have gone to war, and the papers are cried by boys, by old men with squeaky voices or by women.”

“All night long the great searchlights play over the dark and silent city, illuminating every alley and every open spot and sweeping the sky in search of German dirigibles and German airships. The territory round Paris is bathed in light constantly for fear there may be some approach. The spy danger is ever present, and the reservoirs and railroad stations and crossings and bridges are closely guarded. The fortifications are filled with men. The trenches are manned. The city calmly waits the event.”

Step into 1914 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 100 years ago.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now